Terrified mothers and fathers carry their wailing babies and screaming toddlers, struggling to hold them close while rushing away from their houses as quickly as they can.

The handicapped and elderly – some of them very ill, others physically impaired – are ordered to get up from their beds and get out, leaving their indispensable medications behind. They are frantically pushed in wheelchairs – some by family members, some by total strangers – away from homes, hospices and hospitals.

Tear-stained children – their parents trying to quiet them and hurry them at the same time – hear no clear answers to their repeated questions: “Why did they make us leave? When can we go home? What about my friends?” Those who attempt to drive their cars out of town are abruptly halted at checkpoints that bristle with firearms. Terrorists summarily seize their vehicles and confiscate everything that is packed into them. Their orders to drivers and passengers alike are short and to the point: “Get out and walk.”

And so they press on, women, men and children, old and young, moving as hastily as possible towards some uncertain haven. They have left everything behind, with nothing to show for themselves but the clothes they are wearing.

Perhaps far worse, they have witnessed cruelties against friends, neighbors and acquaintances – torturous, terrible barbarism – that will never be erased from their memories.

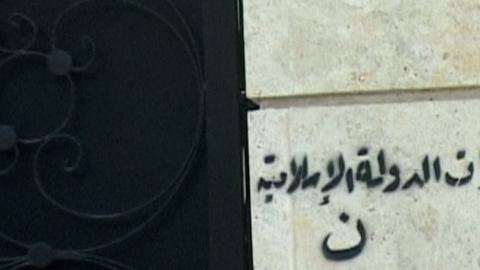

The houses they’ve abandoned – where some of them have lived for generations – are marked in red paint with the Arabic letter nun: representing “Nazarene,” or Christian. In case that isn’t clear, the invaders have added further information: “Property of the Islamic State.”

This final, frantic activity started in earnest at midday on Friday, July 18.

Rumors had been circulating for weeks, and some families had left preemptively. But during those mid-July Friday prayers, the Islamic State (IS, formerly the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria or ISIS) terror group announced in every local mosque that Christians must either convert to Islam, pay an exorbitant Muslim tax – the jizya, which amounts to protection money – or flee.

If the Christians didn’t conform to these demands by noon on Saturday, July 19, there would be “nothing for them but the sword.” And so it was that the nightmare scenario culminated that Saturday, when the Sunni terrorist group expelled the last Christians from Mosul and the surrounding Nineveh Plain.

Those cities, towns and villages had been Christianity’s heartland for 2,000 years.

First the Jews… Assaults on Christians have ebbed and flowed in Iraq since 2003, and from 2011, they spread across Syria as well, leaving behind a bloodstained wake.

Clinging to the faint hope that “this too shall pass,” both Syrian and Iraqi Christians failed to read the proverbial writing on the wall. Only a few foresaw the danger. One was Baghdad’s Monsignor Pios Cacha.

In 2013, the monsignor made a grim prediction. He said that his Iraqi Christian community was experiencing the kind of religious cleansing that had eradicated the country’s once-thriving Jewish community half a century before.

His prophetic words made headlines in Lebanon’s Daily Star: “Iraqi Christians fear fate of departed Jews.”

Father Cacha’s comments were tragically prophetic. As he knew very well, Iraq had, for millennia, been the homeland of some 150,000 Jews. They had been influential, wealthy and well-connected.

But from 1948 through approximately 1970, much like today’s Christians, they lost everything – fleeing the country with nothing but the shirts on their backs.

Today, fewer than 10 Jews remain in Iraq.

For that memorable reason, it isn’t so difficult for today’s Israelis to envision the distress of entire communities being uprooted and expelled – virtually overnight – due to deadly pogroms.

For Jews, such horrors are usually understood to be manifestations of anti-Semitism, combined with other political and religious realities.

And such expulsion wasn’t solely the fate of Polish Jews, or those in other Nazi-infested European nations during World War II.

Very similar stories are woven into the family histories of 850,000-plus Arabic- speaking Jews, who were cast out of the Middle East’s Muslim lands in the mid- 20th century. Many now live in Israel.

Since then, Jews have kept a solemn vow to themselves and their children: Never forget; never again.

It is Western Christians – and particularly North Americans – who struggle to imagine such a brutal ordeal in today’s world. Again and again they ask, “Haven’t we learned to live in peace with other religions and races?” “Hasn’t civilization moved beyond such barbaric abuse?” “Can’t we all just get along?” In short, the answer is “No.”

Saturday people, Sunday people Why? We’ll set aside, for this discussion, the unspeakable treatment of Christians in Iran’s Shi’ite regime.

Instead, let’s consider the substantial number of radicalized Sunni Islamists in the Middle East who are intent on reviving the “golden age” of the Ottoman Empire’s caliphate.

They believe that Islam lost its glorious historical epoch because of impurity and sin; only cleansing will bring restoration.

Thus, their sacred lands must not be defiled by the presence of Jews, Christians or other infidels.

When the Jews were driven out of Iraq in the 20th century, they had been in Mesopotamia and the surrounding areas for more than 2,500 years.

Likewise, today’s Christians are hardly newcomers to the area.

In the first century, two of Jesus’ disciples, St. Thomas and St. Thaddeus (also known as St. Jude), preached the Christian Gospel in territory then known as Assyria – including today’s Iraq. Christian communities established at that time continued, preceding the birth of the Prophet Muhammad by 600 years.

The heartland of Iraq’s Christian community was always in Mosul and the Nineveh Plain, and in recent years other Iraqi Christians have sought refuge there, after enduring escalating bouts of anti-Christian violence.

After the overthrow of Saddam Hussein in 2003, Islamist killers from various factions – sharing a common taste for bloodshed – carried out attacks on Iraq’s Christians. In fact, this reporter covered some of these assaults in the book Saturday People, Sunday People.

In January 2008, a set of choreographed bombings exploded within a few minutes of each other at four churches and three convents in Baghdad and Mosul.

In early March that same year, the archbishop of Mosul, Paulos Faraj Rahho, was reported missing. It was soon revealed that he had been kidnapped, and a ransom was demanded to spare his life. A huge amount of money was required, but the cleric was later found, beheaded, on March 13.

In May 2010, nearly 160 Christians were wounded – some seriously – when three buses carrying Christian students from local villages to the University of Mosul were bombed. A local man was killed by a blast as he tried to help the wounded. The buses were supposedly protected by the Iraqi government.

On Sunday, October 31, 2010 – remembered today as “Black Sunday” – eight terrorists stormed into the Assyrian Catholic Church of Our Lady of Salvation in Baghdad just as Father Wassim Sabih finished the mass.

As the intruders started shooting, the priest fell to the floor, begging for the lives of his parishioners. His assailants silenced him with their guns, holding the rest of the congregation hostage.

A team of Iraqi security forces tried to intervene, but in response the killers threw grenades into the crowd and detonated explosive vests. The final death toll was 57, including two priests.

After these and similar episodes, Christian refugees from Basra and Baghdad crowded into the Nineveh region in search of protection. For a time, there was respite. But now – almost a decade later – they face an even more formidable foe.

On July 29, my Hudson Institute colleague Nina Shea wrote on Fox News: “Before casting out the Christians, Shi’ites and Yezidis, Caliph Ibrahim, as IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi is now called, made certain to take all the possessions of the ‘unbelievers.’ “Cars, cellphones, money, wedding rings, even one man’s chicken sandwich, were all solemnly declared ‘property of the Islamic State’ and confiscated. A woman who gave over tens of thousands of dollars was also stripped of bus fare to Erbil.

“With temperatures in the area reaching a blazing 49°, the last of the exiles left on foot, carrying only small children and pushing grandparents in wheelchairs. Those who glanced back could see armed groups looting their homes and loading the booty onto trucks.”

So it was that a ragtag group of refugees, fleeing for their lives – robbed, raped and otherwise ravaged – were among Mosul’s last Christians. And at the time of this writing, no one can be sure how many other Christians remain today in the rest of Iraq.

What is IS? The IS fanatics who dispossessed Mosul’s Christians were acting under what they believed to be the divinely ordained leadership of Baghdadi, a.k.a. Caliph Ibrahim. A secretive, ruthless and strategy-minded jihadist, he rules over his self-described Islamic State with an iron fist.

Baghdadi has been described by David Ignatius of The Washington Post as the true heir to Osama bin Laden. Ignatius has noted that he is “more violent, more virulent, more anti-American” than Ayman al-Zawahiri, bin Laden’s al-Qaida successor.

After a rocky start in attempting to fulfill his dream of a caliphate in Iraq, Baghdadi’s IS found a new venue. It gained success and stature in the Syrian Civil War, defying both Jabhat al-Nusra’s and al-Qaida’s radical factions by arrogantly displaying its bloodthirsty acts of religious cleansing, particularly against Christians.

In February 2014, the Syrian Christian community of Raqqa was confronted by IS with demands much like those recently faced by Mosul’s Christians.

Rather than flee, Raqqa’s Christians chose to sign a document subjecting themselves to dhimmitude (subordinate status as non-Muslims in an Islamic state) under IS rule, and surrendering to demands that they observe strict Shari’a, as dictated by their overlords.

The subjugation of Christians and Jews to dhimmitude has a long history in the Middle East, and throughout the greater Muslim world. Although it officially ended after the demise of the Ottoman Empire, its humiliating and unequivocal demands have never been erased from communities that suffered under it. And, in various ways, it is still enforced de facto in some modern Muslim states.

Meanwhile, the sadistic behavior of these invaders has defied every known human norm – rapes of entire families; multiple beheadings; mass executions; even crucifixions. More than enough of this has been captured on video and widely disseminated to friends and foes alike.

If terror was their intention, they have certainly achieved it.

When IS warriors swept across a large swathe of Iraq in mid-June 2014, they experienced little resistance from the Iraqi army. In fact, it was widely reported that the army simply melted away. Not only does IS have a reputation for gruesome atrocities, which was no doubt intimidating, the Iraqi military is also disorganized and unmotivated.

IS seems increasingly invincible. Heroic warriors, helping hands Clearly, the Christians that fled from Mosul and Nineveh had few options.

With no money, no vehicles, no passports and no cellphones, they understood that their best hope was to get themselves to Kurdistan, an autonomous region of Iraq that has its own government and practices exemplary tolerance for Christians.

Kurdistan also fields a notoriously ferocious military force called the Peshmerga.

According to Business Insider, “IS fighters stopped when they reached the borders of autonomous Iraqi Kurdistan.

They were facing an opponent that wasn’t going to back off from a fight: the Kurdish Peshmerga, Iraqi Kurdistan’s own highly trained and battle-hardened paramilitary force.”

Thanks to the Peshmerga, which may include as many as 190,000 fighters, many of the Christians who were driven out of Mosul and Nineveh were given safe passage into the Kurdish region. They have found provisional refuge there.

At the same time, Christian organizations with access to Iraqi communities also rushed to lend helping hands – documenting cases, providing emergency assistance and speaking out on behalf of the traumatized refugees.

One well-respected international organization, Open Doors, reported on its website that local churches “… responded rapidly as Christians fled Mosul.”

Raja (not her real name), herself a refugee from Mosul, was able to reach out to the others. She writes: “Shortly after the occupation of Mosul, refugees started coming to our church. When it was time to distribute the relief packages, the families quickly gathered around us. It was overwhelming.

I saw the desperate faces of the old men and the mothers that came to collect their food, and I felt so sorry for them.”

Open Doors’ blog goes on to quote Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein, director of Interfaith Affairs at the Simon Wiesenthal Center.

“Too many of us thought that forced conversions and expulsions of entire religious communities were part of a distant, medieval past. There was little that we could do to stop this horrible episode. It is not too late to realize that many others – Christians today, but certainly Jews, Baha’i, Hindus, Muslims and others – are mortally endangered by a potent religious fanaticism that threatens tens of millions, and which can still be resisted.”

Efforts to religiously cleanse the Middle East have been going on sporadically since the seventh century.

Today, the jihadi slogan, “On Saturday we kill the Jews, on Sunday we kill the Christians,” is being increasingly executed, not only in Iraq, but in Syria, Egypt, Gaza and in several Muslim majority states far beyond – places where few, if any, Jews remain and Christians are, quite literally, under the gun.

Since 2011, thanks to the chaotic upheaval of the so-called Arab Spring, religious cleansing in the lands of the Bible – and particularly the cradle of Christianity – has been implemented with ever-increasing success.

Apart from the Kurdish Peshmerga, there is little resistance and no intervention. World leaders intone “strongly worded” pronouncements, then fall silent. Religious leaders sign declarations; their laymen sign petitions.

And the rest of the world watches and waits, and wonders if anybody cares.

Why is there no opposition? Where will the brutality end? And who will stop it?