"The question is," Humpty Dumpty says in Through the Looking Glass, “which is to be master.” That’s the real issue that underlies all the recent clashes and escalating tensions in the South China Sea, including between the People’s Republic of China and the United States. Since 2007, China has laid down a marker of exclusive sovereignty in the South China Sea and the archipelago of tiny islands known as the Spratlys — even though six other nations have similar claims and even though it’s a waterway through which trillions of dollars of international sea traffic pass every year.

Which is to be ultimate master of the Western Pacific: the rulers in Beijing or the international community backed by the U.S.? Like all such tests of mastery, it’s a question that will never be solved by words alone, only action — perhaps in the last resort military action.

But on Tuesday, words did have their say, and international law and freedom of the seas had a good day in court.

The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague finally ruled on a dispute that’s been brewing since 2012 between China and the Philippines over mineral and fishing rights in the South China Seas. The Court delivered a well-deserved rebuke to China’s serial aggressions in the region. Under the Law of the Sea Treaty, it ruled that China’s claim to sovereignty over the South China has “no legal basis.” It blasted China’s continued construction of artificial islands out of coral reefs and also stated firmly and unequivocally that China had violated Philippine rights in grabbing Scarborough Shoal, one of the maritime landmarks in the area under dispute.

The Court even found that Chinese fishermen, protected by Chinese maritime police and naval ships, had exploited depleted or endangered species of fish and sea life. And Chinese reclamation projects, the Court notes, are destroying fragile ecological systems in the Spratlys.

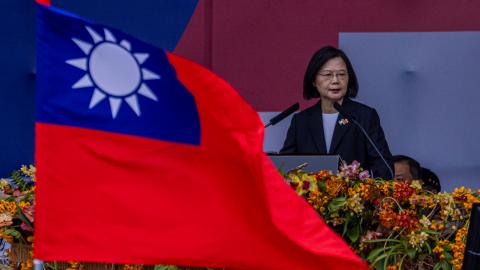

China burst a diplomatic blood vessel at the news and condemned the PCA decision as “a farce directed by Washington.” If only. In fact, one reason that the South China Sea has become such a hotbed of international tension is that the Obama administration has been loath to back the legitimate claims of other countries to the islands and reefs in the Spratlys. (The Philippines, Vietnam, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Brunei all have claims.)The White House has also been ambiguous about asserting the right of free passage around the islands China has claimed and on which it has built air strips that could easily become military assets.

All the same, while PCA’s decision is a victory for the rule of law, there’s a lot more that needs to be done to rein in China’s aggression in the South China Sea.

Certainly we can expect China to hit back. It has said all along that it would ignore The Hague ruling, so it could not back down now without losing considerable face. In fact, Chinese law makes it a crime to surrender a claim of territorial sovereignty once it’s been extended.

Just before the ruling, Xinhua News Agency announced that a Chinese civilian aircraft had successfully tested out its gauges and landing equipment on two new airports in the Spratly Islands — one of which is almost certainly Mischief Reef, an island also claimed by the Philippines. China also announced that a new guided missile destroyer will be sailing from its naval base on Hainan to patrol the South China Sea.

Both moves raise the stakes in what has been all along a high-pressure game of chicken. Who will back down first if China’s sovereignty claims lead to a military confrontation? In other words, who will be master of the future balance of power in the Pacific?

So far the Obama administration has dodged that central issue. It has sent two carrier groups into the Western Pacific. But the sail-bys of Chinese-held islands by U.S. Navy vessels to assert the principle of freedom of passage have been sporadic and ambiguous. And the White House has made little effort to force China to reverse its militarizing moves in the Spratlys.

What’s needed is a robust multinational approach that embraces Japan, Australia, Philippines, and Vietnam, as well as India, Indonesia, and Malaysia, to assert the freedom of navigation the world’s economies depend on, including, ironically, China’s.

French defense chief Jean-Yves Drian has even made the very un-French suggestion that European navies join in, asserting, “If the law of the sea is not respected in the China seas, it will be threatened tomorrow in the Arctic, the Mediterranean, or elsewhere.” It’s a moment a new president can seize, to unite not only Asian but European allies in the cause of upholding an international order that works well for everyone — an order that, once broken, like Humpty Dumpty, can’t be put back together again.