This is part of a series of briefs on United States–China technology competition in Southeast Asia and the implications for countries in the region.

Key Points

- Southeast Asian nations pursue various hedging policies to maximize benefits from larger nations and economies and to manage the risks of overdependence on—and coercion by—these powers. This same approach should be applied to their digital policies vis-à-vis larger powers.

- Data localization approaches and policies are intended to enhance data security, avoid overdependence on external providers, and assist local service providers. However, if not thought through properly or applied too inflexibly, the effect can be the opposite of what long-standing Southeast Asian hedging policies and approaches have attempted to achieve.

- Digital policies (especially data storage and use) invariably have profound geopolitical implications and cannot be ignored or avoided. Southeast Asian nations, especially US allies such as the Philippines, should take this into account.

Introduction

A common—and accurate—narrative in Southeast Asia is that the subregion consists of relatively small and weak countries in a broader Indo-Pacific region populated by giants. Due to the countries’ small size and relative lack of power, policymakers here do not define statecraft as shaping or changing their environment. Instead, they define it as maximizing their countries’ rights and benefits in any given strategic environment and managing risks associated with weakness.

Leaders in the region are transferring this mindset to their approaches to the digital economy and technology. Southeast Asian policymakers are increasingly discussing the importance of having a unified and coherent national strategy to reduce the risks of overdependence on—and capture by—technological superpowers such as the United States and China. For example, an increasing number of voices are making the case for sovereign artificial intelligence (AI), a system controlled by one or several trusted Southeast Asian governments rather than entities in one of the great powers.1 They are concerned that technological progress is heavily dependent on advances in the largest economies and that the AI stack (the infrastructure, technologies, and frameworks that build, teach, deploy, and manage AI applications) is mainly controlled by the US or China.

With respect to the broader digital economy, debate is focused on data localization, which refers to where national security data should—or must—be stored and how it is processed. Vietnam has been an early mover, with a stringent set of data localization laws and regulations. For example, Decree No. 53/2022/ND-CP from 2022, which elaborates on the country’s 2018 Law on Cybersecurity, mandates that foreign entities providing a wide range of services must store specific user data in Vietnam and establish an office in the country.2

In recent months, attention has been on the Philippines, where pressure on local and foreign entities to store data locally has increased. Furthermore, the government has drafted laws to implement a data localization policy for national security purposes,3 and the Department of Information and Communications Technology has released “Policy Guidelines on Data Residency and Data Classification for Government Agencies” and a “Workplan for Data Sovereignty and Data Localization for Data Governance.”4

Beginning with a case study of the Philippines, this brief argues that there are serious—albeit unintended—business, data security, and cybersecurity risks in implementing data localization policies that are not well thought through. Moreover, it argues that digital policies should be understood in a broader geopolitical context defined by the US-China rivalry and by different conceptions of interests, values, and ethics. Southeast Asian nations cannot avoid this contest, and their digital policies will have geopolitical implications for their nations and the region.

Case Study: The Philippines

Data localization provisions in the Philippines are among the least onerous in Southeast Asia (see table 1 for a comparison of data localization and cross-border transfer rules). There are no broad localization requirements, although banks and government entities are obliged to retain local copies of relevant data as a safety measure. The 2012 Data Privacy Act governs data policy, which generally regulates data processing using the light-touch principles of consent, contractual agreement, or legitimate interest. The National Privacy Commission oversees the evolving rules, as well as defines and adapts these principles of consent, contractual agreement, and legitimate interest to safeguard data privacy and security.

Table 1. Comparison of Data Localization and Cross-Border Transfer Rules in Southeast Asia

|

Country |

Localization Requirement Strength |

Cross-Border Transfer Rules |

Main Supervisory Authority |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Indonesia |

Moderate to strict (sectoral): Public sector and financial data must be localized; private non-financial organizations may use offshore storage under oversight |

Transfers allowed if (1) recipient jurisdiction ensures equivalent protection, (2) contractual safeguards exist, or (3) explicit consent is given; pre/post notification to the ministry required |

Ministry of Communications and Digital Affairs (Komdigi); in future, Data Protection Authority |

|

Singapore |

Low: No general localization; limited sector-specific obligations (e.g., banking, healthcare); actively promotes cross-border flows |

Transfers permitted if recipient jurisdiction ensures equivalent protection; mechanisms include contracts, binding rules, participation in Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Cross‑Border Privacy Rules, consent |

Personal Data Protection Commission |

|

Malaysia |

Low to moderate (sectoral): Some industry regulators (e.g., financial, telecoms, healthcare) impose restrictions; no blanket localization |

Transfers allowed if recipient jurisdiction ensures equivalent protection |

Department of Personal Data Protection (under Ministry of Digital) |

|

Thailand |

Low: No general mandate, but sector regulators (e.g., financial, telecoms) may impose storage obligations |

Transfers allowed if (1) recipient jurisdiction ensures equivalent protection, (2) safeguards exist (e.g., contractual clauses, Binding Corporate Rules), or (3) consent is given; framework is similar to the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation privacy law |

Personal Data Protection Committee |

|

Philippines |

Low to moderate (critical sectors): No broad localization, but banks and government entities may be required to store data backups locally |

Transfers allowed where recipient jurisdiction ensures equivalent protection; alternatives include contracts and consent |

National Privacy Commission |

|

Vietnam |

High (broad localization): Foreign service providers (e.g., telecoms, online services, e-commerce) may be requested to store user data locally and may also need a local office or branch |

Offshore transfers of personal data, important and core data subject to Ministry of Public Security notification or approval; must satisfy consent, necessity, and safe handling; strictest in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations |

Ministry of Public Security |

|

Cambodia |

Minimal (developing framework): No general localization law; some restrictions in banking and telecoms |

No omnibus law; transfers generally allowed with consent or contractual arrangements; future law will likely introduce adequacy or safeguard models |

Currently sectoral regulators (e.g., National Bank, telecoms regulator); draft personal data protection law is pending |

Source: “Data Localization and Transfer Issues in Southeast Asia,” Rouse, September 26, 2025, https://rouse.com/insights/news/2025/data-localization-and-transfer-issues-in-southeast-asia-what-businesses-need-to-know#_ftn1.

The recent proposals in the Philippines—which considered changing data localization provisions to enhance national security, data sovereignty, and control over the use and storage of locally generated data—made far-reaching changes to compliance requirements for data localization and went much further in intent. Policymakers are reworking the changes, and more recent versions appear to apply more stringent localization standards for some forms of government data. However, the initial proposals would have applied to multiple sectors and excluded US external cloud service providers from three of the four tiers of public sector data. The proposed new regulations would have placed limits on what US cloud providers could supply or deliver to Philippines-based public sector and private sector clients, whether headquartered in the Philippines or elsewhere.

Local conglomerates, telecoms, and data centers in the Philippines would have been the primary beneficiaries of these changes.5 Chinese cloud service providers would also have benefited because they were not placed under the same restrictions in earlier drafts. It may be that protecting local firms was a motivation for the early drafts. Regardless, the earlier proposed changes, though not explicitly linked to any national movement toward a sovereign AI framework, were a product of the belief that a smaller country and economy must protect itself from external dependence and capture.

The Business Case Against Stringent Data Localization

Data is now becoming a more important driver of economic growth, innovation, and productivity than hard commodities like oil and minerals. Unlike hard commodities, it is scalable and grows exponentially more valuable with greater range and volume. The more data that firms can collect and access, the better and more useful the algorithms, which in turn attracts new users to exponentially accelerate the virtuous process. AI further accentuates the importance of data, which has become a strategic commodity and a determinant of current and future economic power and technological prowess with immense strategic value. This is why Southeast Asian countries are reconsidering their data localization (and regionalization) policies, and this is what has driven the Philippine conversation outlined above.

Many business and industry groups were against the earlier Philippine proposals. For example, the Global Data Alliance, a coalition of companies with offices and stakeholders in North America, South America, and Asia, argued that the data localization proposals outlined earlier would have harmed the Philippines economically by reducing productivity, increasing data storage and processing costs, slowing innovation, and disincentivizing foreign direct investment in AI-related sectors.6

To be sure, the business case for stringent data localization measures is poor. The more data is shared, including across borders, and drawn from diverse sources, the more scalable and valuable it becomes. But extracting value from data also requires enormous amounts of capital to gather, apply, and process datasets in useful ways. To do that, companies need digital and fast computing infrastructure as well as increasingly sophisticated AI capabilities, which require access to data across borders to become more potent. This requires an enormous amount of capital, to which Southeast Asian economies other than Singapore do not have access. As a country’s data storage and data processing laws and regulations become more inward-looking, it becomes less attractive to global capital, and its ability to create value from access to, and processing of, data is more inhibited.

In other words, the more countries silo their data, the farther behind they fall in extracting benefits and opportunities from global firms and economies, and the less capable they are of accessing and gaining an advantage from digital innovation. The point is that Southeast Asian nations that excessively silo data will fail their own benchmarks for economic and commercial statecraft. In a modern digital context, stringent data localization upends the enormously successful East Asian model of economic development, which led to accelerated economic growth and rising prosperity for small economies such as Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand in the last quarter of the previous century and the first decade of this one. This model was based on importing capital, innovation, and know-how to dramatically increase productivity and bind these smaller economies to successful larger economies in North America and Europe.7 If these countries shut themselves off, they will experience economic and technological stagnation in these sectors.

The Illusion of Security Through Localization

Some argue that the digital dynamism a country produces when it has minimal digital and data borders should be balanced against the imperatives of data security and cybersecurity. This supposed trade-off mirrors the arguments of those advocating for sovereign AI.8 They assume that the more dependent a country is on external data storage and related technologies, the less resilient and secure it becomes because it loses national and sovereign agency and control.

Many analysts also assume that countries can minimize cybersecurity risks by requiring local data to be stored and processed locally rather than externally by third-party providers. But evidence rarely shows this to be the case.

The reality is far more multifaceted and complicated. For a start, localized data storage becomes a vulnerability if a localized disruptive or destructive event occurs. For example, the 2011 Tokyo earthquake destroyed local data storage facilities and backups and caused outages at several local infrastructure providers.9 In contrast, customers of hyperscale cloud services remained online. In September 2025, a fire at a single data center in South Korea caused millions of users to lose access to hundreds of digital public services, such as postal and mobile identification services.10 In Southeast Asia, earthquakes, floods, storms, and man-made disasters such as wars can cause considerable risk for entities that rely only on local data centers. As an example, with Russian forces occupying parts of eastern Ukraine in 2022, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy signed a resolution allowing sensitive government data to be stored with trusted partners outside of Ukraine. As the country’s then–Vice Prime Minister Mykhailo Fedorov explained, “Russian missiles can’t destroy the cloud.”11

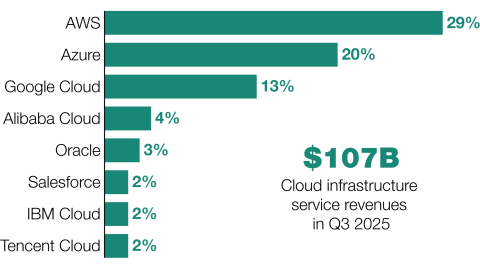

Moreover, cloud-hosted servers operated by companies like Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud Platform allocate considerable resources to cybersecurity. While these firms do not release annual figures on their cloud-server data protection spending, the numbers are likely in the billions of dollars. Furthermore, individual data breaches cost these firms millions of dollars and much more in terms of their brand and standing. These three firms enjoy approximately 62 percent of the global cloud market in 2025 and compete fiercely for market share.12 They, and other major providers, have an incentive to invest heavily in cybersecurity.

Cybersecurity relies on practices such as access control management, data encryption, on-site security and monitoring, and firewalls, which need to be implemented no matter where data is stored. Data centers in the Philippines or Vietnam are not inherently more secure than those in the United States or United Kingdom, and localization does not, in and of itself, increase cybersecurity.

In fact, locally owned data centers in countries like the Philippines are unlikely to have the resources or in-house expertise to offer the same level of security as data centers in more developed countries. The cost of doing so would also be prohibitive.

In short, a stringent data localization requirement could force local firms to store data in servers with significantly lower cybersecurity standards and capabilities than what is available from an overseas cloud provider.

Geopolitical Considerations

This brief does not recommend that governments implement a globally unified digital economy where data can flow freely across all borders. Such a regime is unrealistic and dangerous because competing geopolitical interests and values lead to different ethical and practical approaches to the use of data.

For example, the European Union’s data policy emphasizes personal privacy and individual rights. The US seeks to walk a middle ground between protecting personal privacy and individual rights on the one hand, and a more business-friendly approach that enables the use of data for commercial purposes on the other.13

The Chinese approach is the one most at odds with the EU and US approaches, as it gives the state a central role in regulating the flow and use of data. Rather than focusing on the relationship between data processors and data subjects, as Western countries do, Beijing upholds the state as the unchallenged keeper and processor of data. The Chinese approach offers minimal consideration to personal privacy and individual rights. Instead, state entities have a virtually untrammeled right to gather, use, and share data in any way they consider necessary to advance state and Chinese Communist Party objectives, which includes attaining commercial leadership in the global digital economy, with a growing emphasis on AI applications

Chinese legislation reflects this approach, such as in the 2017 Cybersecurity Law,14 which affirms state control over cyberspace, including digital data. Importantly, according to a declaration and clarification of rules released in 2019 by the Chinese State Administration for Market Regulation and the Standardization Administration of China, Chinese cloud computing platforms operating overseas must follow Chinese laws and regulations. This includes Chinese national standards that require customer data and personal user information processed by cloud services to be stored inside China, whether the clients are inside or outside the country.15

Chinese state or commercial entities can process any data stored with Chinese cloud service providers if granted permission from state authorities. Rather than taking a rights-based approach to data management as in the West, China treats access to data (originating inside or outside of the country) as a tool for realizing the state’s objectives.

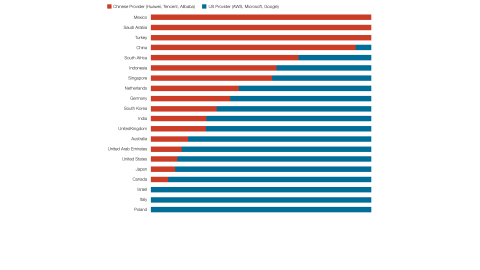

For this reason, the common belief that the United States and China are competing for digital dominance in the global economy, including for cloud service provision, and are simply pursuing different strategies, suggests a false equivalence (see figure 1). The US government and US-based tech giants negotiate, argue over, and disagree on rules and practices on an ongoing basis. Importantly, American big tech companies do not exist primarily to pursue objectives mandated by the US government. In contrast, China’s notion of cyberspace sovereignty is about directing and mandating that all private and public entities pursue objectives set out by Beijing.16 This includes imposing laws, rules, standards, and practices on Chinese firms to achieve Beijing’s political, technological, and economic objectives.

Figure 1. Chinese and US Cloud Service Market Share in Selected Economies

Source: Katharina Buchholz, “Where Chinese or American Tech Is Used in Cloud Data Storage,” Forbes, April 17, 2025, https://www.forbes.com/sites/katharinabuchholz/2025/04/17/where-chinese-or-american-tech-is-used-in-cloud-data-storage/.

Policies concerning data storage and use are not only technical and commercial matters but also have geopolitical implications. Countries, as well as clients of data storage services, need to accept that there are different interests and values in play, and their decisions have broader—and serious—consequences, for both the countries and their geopolitical environment.

Consider the data localization discussion in the Philippines over the past few months. While precise market share figures are not available, it is well-known that US firms Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud Platform are the dominant cloud service providers in the market. Chinese firm Alibaba Cloud, though behind the US firms in market share, has a significant presence in the Philippines and importantly, built a data center there in 2021.17

There are two related points to be made. First, a focus on restricting the market share of the dominant international cloud service providers to allow other entrants and prevent over-dependence would generally mean targeting the US giants because they dominate the market in many economies. Figure 2 shows the worldwide market share of the three largest US cloud providers—which, as noted previously, have 62 percent, while Alibaba Cloud has 4 percent and Tencent Cloud 2 percent.

Figure 2. Worldwide Market Share of Leading Cloud Service Providers, Q3 2025

Source: Felix Richter, “AWS Stays Ahead as Cloud Market Expands,” Statista, November 4, 2025, https://www.statista.com/chart/18819/worldwide-market-share-of-leading-cloud-infrastructure-service-providers/.

However, restricting market share and targeting the US giants will decrease the likelihood that these companies and other Western firms will invest in data infrastructure in the local market. This, in turn, increases the likelihood that these countries will have substandard infrastructure and a stagnant local digital market starved of foreign capital. In such situations, countries tend to increase their reliance on cheaper, subsidized Chinese offerings in the long term.

Second, the earlier draft versions of the Philippine data localization policies excluded the large US cloud service providers based on data localization requirements. The proposed new rules, in contrast, likely would include Alibaba Cloud because it has servers in the Philippines. This might mean that the Philippine government will be storing sensitive or even classified data with a Chinese firm that is obligated to store overseas data on servers inside China and make it available to the Chinese government. If so, this would be an unintended and catastrophic result of policies that were designed to improve national data security and cybersecurity.

Finally, there is a geopolitical contest disguised as a digital data and AI contest in which China plays by different rules than Western countries, both nonmarket and commercial. Beijing is implementing a campaign to dominate the digital data and AI sectors and applications. It is doing so by funding an enormous state-directed infrastructure expansion; pursuing military-civil fusion; and entrenching its infrastructure, commercial presence, rules, and standards in developing markets in the so-called Global South.18

With respect to developing economies in Southeast Asia, China’s Digital Silk Road framework, which is part of the Belt and Road Initiative, seeks to assist countries such as the Philippines to overcome “digital gaps.”19 Unlike Western and other democratic political economies, China can harness public and private assets, capital, and capabilities to plug these gaps with Chinese services and solutions to entrench and bind the recipients to a Chinese technological ecosystem—and the values and standards that come with it. Whether that presents an unacceptable compromise of data security is a decision for each nation to make. But if maximizing data security and autonomy is the objective, data localization policies applied in the wrong way might well achieve the opposite.

Conclusion

Many Southeast Asian nations pride themselves on living, managing, and getting the best out of existing in a region occupied by giants. Their various strategic hedging strategies are based on maximizing gains and managing or minimizing risks. The digital economy has its own commercial and technical dynamics and nuances. However, decisions must be understood in their broader geopolitical context.

The specific issue is the trend toward championing data localization, for which the Philippines provides a case study. The broader issue is how smaller Southeast Asian nations and economies can maximize both commercial and security outcomes while managing associated risks in the digital economy. The overarching issue is the unavoidable geopolitical implications of their digital policies for their country and region.

The conclusion is not that data localization in any form should be abandoned. It is rather that the economic, data security, cybersecurity, and geopolitical implications of different options ought to be accurately, properly, and thoroughly assessed lest policymakers make decisions with enduring ramifications too blithely.

Google sponsored the research behind this brief. For more information about supporters of Hudson, please see pages 73–75 in our Annual Report 2024, available here.