Twenty-five years ago, mere weeks after the Chinese military violently ended a pro-democracy demonstration at Tiananmen Square, national security adviser Brent Scowcroft traveled to Beijing to toast the very leaders who ordered the massacre. In diplomatic affairs, and especially in an image-conscious society such as China, the visual matters. Scowcroft's overture sent the wrong signal to the Chinese -- of business as usual. There would be no real costs to the Beijing government's brutal violation of human rights.

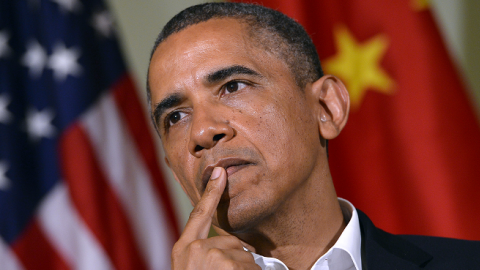

We took the wrong approach with China then and, as an embattled President Obama undertakes a pivotal trip to China this week, it would be a mistake to repeat that approach. Indeed, Obama could have one last chance to recalibrate relations with the Middle Kingdom to one that is more to America's advantage.

Sensing weakness

In one sense, Obama's position is not strong, especially after his rebuke in the midterm elections. His visit to China will perhaps mark the last time a U.S. president arrives there with America's economy No. 1 in the world. (By some measures, China's economy is already bigger.) His entreaties to Beijing for assistance on the Islamic State terror group, Ebola and countering Russian aggression in Ukraine have been met with silence or shrugs.

Despite a personal visit in September from national security adviser Susan Rice to ask for cooperation to curtail ISIL's influence in the Middle East, China has committed nothing. Instead, China is obviously trying to fill a perceived vacu-um of U.S. leadership and interest in the region. Within weeks of Rice's visit, Chinese battleships conducted their first-ever exercises with, of all countries, Iran.

Though U.S. leverage with China is declining -- rapidly -- it has not yet vanished.

For one, the United States can do more to publicly apply pressure on the Chinese to play the constructive role in world affairs that Beijing long has claimed to seek. On Ebola, on ISIL, on Russian belligerence, the Chinese should be held to account for the apparently deliberate decision to avoid meaningful cooperation.

On human rights, Obama finds himself surrounded by sharply divergent opinions. The outgoing Senate Judiciary Chairman Patrick Leahy supports strong warnings on Hong Kong. House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi has urged that direct talks with the Dalai Lama must begin. The president has an opportunity to demonstrate common cause with remaining moderates in the Politburo who seek to forestall an even more brutal Tiananmen-style crackdown.

Tough words

As a nod in that direction, Obama could publicly raise the name and status of his fellow Nobel laureate and democracy activist Liu Xiaobo, who is spending his sixth year in a Chinese prison.

With China quietly working to curtail American interests, it makes absolutely no sense to continue to pick fights with Japan, a needed ally -- and China's arch rival. Instead, the president should revisit themes from his visit to Tokyo last April, when he supported Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's effort to interpret the Japanese Constitution to allow Japanese forces to be deployed in defense of allies -- something that Japan has been reluctant to do since World War II. China stridently criticized Obama's comments for weeks, a sure sign of its impact. It is time to make this point again.

The president must use carrots as well as sticks. Obama must try again to persuade Senate Democrats led by Harry Reid to drop opposition to the administration's request for trade promotion authority, which stands in the way of a bilateral U.S.-China investment treaty that demands equal treatment for our companies as China gives its government-controlled corporations.

Obama so far has remained silent, at least publicly, on China's quiet but rapid military buildup. That silence should end in Beijing. So, too, should the president's decision to mostly overlook China's active and aggressive cyber campaign against American corporations. Attorney General Eric Holder indicted five alleged Chinese cyber criminals. The president might well go further.

How the U.S. negotiates its relationship with an ascendant People's Republic of China will define both of our fates for the remainder of this century. If Obama follows Scowcroft's precedent, his trip could well be seen as another moment when we had an opportunity to try to change China, but let it pass.