Executive Summary

The Russia-Ukraine War has strengthened military-industrial ties between Moscow and Tehran. Most concerning is their deepening collaboration in dual-use technologies and disruptive weapons systems. Moscow has provided technical assistance to Tehran in key areas, including its space program, which can help the Islamic Republic develop intercontinental ballistic missiles. Moreover, Iran’s interest in Russian anti-stealth radars and air-superiority fighters is worrying. Russia’s extensive use of Iranian-supplied drones has allowed the Iranian defense technological and industrial base to advance its drone warfare systems, collect large amounts of operational data, and improve its loitering munitions designs and production. A Russian victory in Ukraine would likely accelerate such cooperation, given the two countries’ geopolitical ambitions, among other factors. So far, the Islamic Republic has been the winner of the Russia-Ukraine War.

Below are some key highlights from this policy memo:

- The Russian military’s reliance on using munitions from Iran to exhaust Ukraine’s combat capabilities has provided Tehran with unprecedented opportunities.

- In the absence of adequate deterrents in place, Iran has already become a combat drone supplier to the world’s second-largest arms exporter, the Russian Federation, turning the Islamic Republic into a menacing threat to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) on the alliance’s eastern and southern fronts.

- Open-source intelligence tracks a meaningful rise in the Russian military’s use of Iran-supplied Shahed baseline loitering munitions, indicating that the joint Russo-Iranian drone plant in Tatarstan, Russia, is capable of producing scores of kamikaze drones annually at low cost. Such facilities can soon mushroom across the Russian Federation.

- With Tehran demonstrating growing control over its airspace while the country moves closer to obtaining military-grade nuclear capabilities, Russia can help the Islamic Republic make its airspace more dangerous than ever. A combination of anti-stealth radar, the Su-35 air-superiority fighter squadrons protected by underground basing, and a large number of layered strategic air defenses can prove lethal even against fifth-generation, stealth combat aircraft.

- Accordingly, the Western intelligence community should remain vigilant over any cooperation between Moscow and Tehran involving anti-stealth radars and space program assets, keeping in mind that the latter can easily translate into intercontinental ballistic missiles.

- Finally, Iran is now investing in infrastructure within Russia—including dredging the Volga River and establishing shipping companies in the port city of Astrakhan—allowing the two countries to further expand the strategic route across the Caspian Sea and the Sea of Azov.

Drone Warfare Data Shows How Iran Has Gained during the War in Ukraine

While high-profile items like the Su-35 air-superiority fighter and the S-400 strategic surface-to-air missile (SAM) system make the headlines, the most important gains Tehran has made during the Russian invasion of Ukraine have been in the realm of drone warfare. The numbers illustrate just how potent Iran’s drone warfare capabilities have become. With the war, the Iranian defense technological and industrial base has gained access to a giant database obtained from combat operations. Such input is invaluable for running critical military programs.

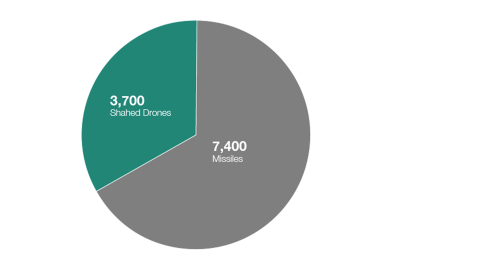

Between September 2022 and December 2023, Russia launched some 3,700 Shahed-131 and Shahed-136 drones, averaging between 200 to 250 drones per month. The number of drone salvos rose dramatically in the last months of 2023. These assets were launched year-round, and under varying weather conditions.

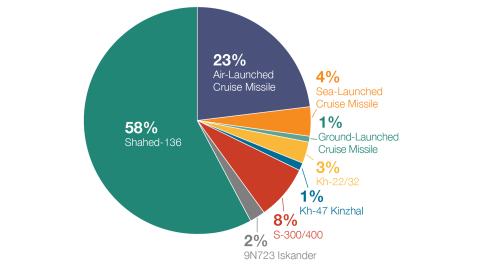

Russia has launched Iran-supplied drones in strike packages alongside a variety of other offensive weapons, ranging from hypersonic aeroballistic missiles to cruise missiles and air-launched anti-ship missiles. Iranian loitering munitions have been tested against a broad range of defensive assets, including Western and Russian SAM systems and electronic warfare capabilities; on occasion, up to 60 percent of Russian strike packages have featured loitering munitions manufactured by Tehran.

Not only is Iran supplying Russia with large quantities of loitering munitions, but it is also manufacturing a dizzying number of variants. A diverse array of Shaheds continues to target Ukraine, including the Shahed-238 jet-powered variant, the Shahed-136 equipped with tungsten balls and fragmented shrapnel warheads, the Shahed-136 with thermobaric warheads, and newer variants featuring special coatings that decrease the drones’ radar signatures. Drone wreckage has shown that some variants even possess Kyivstar SIM cards and modems that allow them to map out Ukrainian air defenses.

The numbers leave no doubt, as figures 1 and 2 show: Iran possesses a complex defense ecosystem capable of using data obtained from its operations in Ukraine to modernize its drone warfare assets even further.

The Russia-Iran Drone Plant and the Potential Threat to NATO’s Eastern Front

The marked increase in both the number of Russian salvos and the proportion of Iranian loitering munitions involved in those strikes can mean only one thing: that the drone plant in Tatarstan operated jointly by Russia and Iran is producing prolifically.

According to press resources, Russia and Iran have agreed on a three-stage plan for the facility. The initial phase of production is designed to produce 100 drones per month, while the second and third stages are meant, respectively, to ramp production up to 180 and 226 loitering munitions per month. In the first and second stages, Iran is to deliver critical components such as engines, with the Russian defense industry gaining full design and production capacity in the third phase.

With the Tatarstan facility up and running, the prospects of similar operations mushrooming in different corners of Russia have only risen. Such a development would pose a grave threat to NATO’s eastern front.

It would be especially worrisome because Iran’s modus operandi is designed to stymie traditional arms control regimes. Most of its critical requirements for drones, especially loitering munitions with low unit costs, rely on commercially available subsystems that do not fall under the Missile Technology Control Regime or the Wassenaar Arrangement’s dual-use lists. Thus, while current export controls can make life harder for the mullahs, they cannot decisively prevent Tehran from taking advantage of international commercial technology markets. Iran can always obtain lower-end items in quantities sufficient to sustain its production lines.

To close the loopholes in traditional arms control regimes and outdated export control policies, recent studies recommend implementing catch-all controls and holding firms responsible if their products end up in Iranian weapons systems.

A Look Inside Iran’s Shopping Cart in Russia

According to comments from Iran’s deputy defense minister, Mahdi Farahi, to Tasnim News Agency, the semi-official Tehran information bureau associated with the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the Islamic Republic has been pursuing a troika of Russian systems: the Su-35 super-maneuverable fighter, the Mi-28 attack helicopter, and the Yak-130 light-attack jet aircraft. Additional acquisitions may also be in the offing; while Iranian leadership turned down a recently proposed deal for S-400 strategic SAM systems, indicating that their very own Bavar-373 suffices to protect the country’s airspace, Western news outlets do not rule out the prospect of Tehran reviving the deal.

Why Does the Su-35 Matter?

With an air force that has been using an air deterrent from the time of the shah to patrol a huge national airspace, the Su-35 is a catch for Iran.

A capable member of the Flanker baseline, the Su-35 is a true air-superiority fighter with high-end kinematic features. The aircraft has a better thrust-to-weight ratio than its predecessor, the Su-27, and in aviation lingo it is super-maneuverable: it can perform controlled maneuvers that would be impossible to perform with conventional aerodynamics.

The Su-35 possesses thrust-vectoring Saturn AL-41FS turbofan engines that can independently point in different directions, allowing the aircraft to move in one direction while its nose points in another. With its potent agility and Mach 2.25 maximum speed, high angles of attack, as well as R-73 missiles that can be fired off-boresight by a pilot using a helmet-mounted sight to target another aircraft just by looking at it, the Su-35 is a dangerous beast in aerial warfare, especially against fourth- and 4.5-generation Western fighters.

The Su-35 also possesses robust capabilities in beyond-visual-range aerial combat. The aircraft’s X-band passive electronically scanned array (PESA) Irbis-E radar is an incredibly powerful sensor, with a detection range of nearly 250 miles for a target with a 32.3-foot radar cross-section, comparable to the range of a standard fourth-generation fighter. While the Su-35, like the other members of the Flanker baseline, is a large platform with high-thrust engines that increase its risk of detection, it would be formidable in a preventive strike scenario involving only tactical aviation assets, where an adversary’s air force would have to operate within Iranian airspace with little chance of conducting combat search-and-rescue missions for ejected pilots at scale.

When combined with layered air defenses—especially strategic SAMs and potentially Russian S-400s—the Su-35 would provide Iran with a deadly deterrent. Any tactical aviation package attempting to halt the Iranian nuclear program would encounter difficulties if Tehran were to use anti-stealth, high-band radars to support Su-35 combat air patrols. Moreover, Iran has been diligently building underground bases for its air power, which would significantly increase Su-35 squadrons’ resiliency against surprise attacks.

Finally, possessing the Su-35 would provide Iran with more than the aircraft itself: it would also bring the fighter’s technologies into the mullahs’ hands. Iranian engineers would no doubt use their new possessions to develop a complete understanding of the aircraft’s systems and subsystems—from radar and sensors to mission computers and engines—and use this knowledge to the country’s advantage.

Iran’s Acquisition of the S-400 Cannot Be Ruled Out

Western writings highlight the S-400 strategic SAM system as Iran’s primary request from the Kremlin. While Iranian officials deny these reports and are quick to praise their Baar-373 SAM, Tehran could still move forward with the deal for the S-400.

Iran possesses many similar systems already. The 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) paved the way for Russian deliveries of at least four S-300 PMU-2 batteries to the IRGC, batteries currently deployed in Bushehr, Isfahan, and Tehran with an eye toward protecting the Fordow nuclear site, according to open-source reports. Moreover, Iran is estimated to possess up to 60 S-300 transporter-erector-launcher (TELARs) units.

Iran also has its own strategic SAM systems, dubbed the Khordad 15 and Bavar-373. The latter is reportedly a near-equal to the S-300 baseline, though Iran’s strategic SAM systems have not yet seen their combat debuts. Apart from its high-altitude and long-range strategic air defense systems, Iran also operates mid-altitude Soviet-Russian Buk and SA-6 air defense systems that are compatible with its strategic Russian SAMs.

Nonetheless, a more crowded SAM configuration—augmented by S-400s—could make Iran’s airspace markedly more dangerous, especially if military options become necessary to halt the Islamic Republic’s march toward nuclear capabilities. A more complex SAM architecture in Tehran’s hands would complicate the necessary effort at suppression and destruction of enemy air defenses (SEAD) that would need to occur as a prelude to possible preventive strikes on its nuclear program. Networked S-400 batteries operating in tandem with Su-35s cued by anti-stealth, high-band radars, as well as scrambling air-superiority fighters taking off from underground bases, would make any attacking force think twice.

The Impact of the Mi-28 Attack Helicopter

The Mi-28NM “Night Hunter” attack helicopter lurks below the radar of many Western analysts assessing Iran’s potential acquisitions. But the US and its allies should be alarmed by Tehran’s interest in the Mi-28. Its procurement would strengthen the Islamic Republic’s deteriorating rotary-wing deterrent and vastly enhance numerous subsystems that Tehran currently finds wanting.

With recent upgrades to the Mi-28 baseline, the Iranian defense technological and industrial base could get its hands on important engine and sensor technology by acquiring the helicopter. The upgrades, initiated jointly by Klimov and the Russian Rostec Corporation, provide the aircraft with a modernized automated control system and a VK-2500 baseline engine. The new VK-2500P engine is designed to boost the major maintenance threshold of the baseline from 2,000 to 3,000 cycle hours, and the overall lifespan of the engine from 9,000 to 12,000 cycle hours.

Following its use in Syria, the Mi-28 also received a major radar upgrade. The new variants come equipped with the N025E over-the-hub radar, a capable sensor with a ball-like feature over its rotor. According to Russian press sources, the 360-degree visibility of the new radar enables the attack helicopter to obtain a radar image of an operations area, which it can then use to hide in uneven terrain behind obstacles. This allows its pilots to ambush ground targets without risking exposure.

In short, Iran will look to any potential Mi-28 deal for more than a mere upgrade of its arsenal. If the deal goes through, Iranian engineers will spend long hours understanding and copying the Russian gunship’s systems for the benefit of the Islamic Republic.

The Yak-130: More than a Trainer Jet

The mainstream Western press has described the Yak-130 as a humble trainer jet. While it is indeed a trainer aircraft for Russia’s advanced fighters, depicting the Yak-130 only as a trainer undersells the aircraft’s capabilities.

Available writings suggest that the Yak-130 is configured for combat roles. The aircraft comes with an able avionics package, including a helmet-mounted display and fly-by-wire features, as well as GPS- and GLONASS-compatible targeting and navigation technologies. The Yak-130 has a reliable thrust-to-weight ratio married to an array of climb attributes. Due to its design principles, some experts even claim that the aircraft can compete with legacy fourth- and 4.5-generation fighters like the Mig-29. The Yak-130’s set of nine hard-points supports air-to-air and air-to-ground weapons systems certification, and the jet also possesses a laser range-finder and camera to augment its effectiveness in warfighting.

In September 2023, visuals released by Tehran confirmed that the Iranian Air Force has indeed received deliveries of the Yak-130, and has deployed a squadron in Isfahan. While the aircraft will not alter the balance of power over Iranian airspace, its presence in the country suggests that Iran is moving closer to securing the Su-35 deal.

The Caspian–Azov Route: An Alarming Linkage between Russia and Iran

The rise of seaborne trade between Tehran and Moscow through the Caspian Sea and the Sea of Azov has generated a new security risk in the region, raising eyebrows in the United States intelligence community that the sea route could be used to facilitate arms transfers to the Russian military. Notably, it was in September 2022—immediately after traffic through the Caspian began to pick up—that Russian forces launched their first Shahed baseline loitering munitions in Ukraine. Alarmingly, many vessels that traverse the Caspian–Azov route navigate with their Automatic Identification System (AIS) signals turned off, according to maritime intelligence reports.

While the Caspian Sea is landlocked, low-tonnage vessels can travel between the Caspian and the Sea of Azov via the Don and Volga rivers using the Volga–Don Canal. The low probability that arms-carrying vessels could be searched and seized makes the route an optimal pathway for the transport of illicit weapons.

Moscow is trying to capitalize on these advantageous circumstances by building more cargo ships in the Astrakhan Shipyard. To further augment Russia’s shipbuilding industry amidst ongoing sanctions, Russian President Vladimir Putin has approved the transfer of the shares and management of the United Shipbuilding Corporation (USC) to majority state-owned VTB Bank for a period of five years. India is also lending a hand; the state-owned GOA Company is now building 24 vessels for the Kremlin that are capable of navigating the Caspian. This project is on track to be finalized in 2027.

In the meantime, Iran is doing its part in bilateral strategic transactions. Iranian investors are starting companies in Astrakhan and investing heavily in the shipping business there. Iranian companies are also taking part in the dredging of Russia’s rivers that makes the Caspian–Azov route navigable.

Red Flags Worth Monitoring

With bilateral ties between Iran and Russia strengthening, two potential nodes of cooperation between the nations remain worth monitoring: anti-stealth radar networks and space-related technologies. Fostering Iran’s capabilities in these two areas would give a special boost to the country’s geopolitical ambitions. While anti-stealth radar architecture could help Iran protect its airspace from preventive strikes, space-related technologies could equip its nuclear program with an ICBM option it does not currently possess.

Anti-stealth Radar Networks

Anti-stealth radars theoretically allow Russia’s integrated air and missile defense systems to detect Western fifth-generation tactical military aviation platforms, although their detection quality is poor enough to give the fifth-generation assets time to engage the SAM systems first. Besides, such detection does not necessarily offer weapons-grade target acquisition data. The SAM systems still have to rely on engagement radars. So while anti-stealth radar sensing does not guarantee dominance, a combination of high- and low-altitude combat air patrols by advanced Flankers, a variety of overlapping SAM envelopes, and anti-stealth radars can alter the odds in any given fight by directing interceptor missiles and fighter aircraft into certain sectors that the fifth-generation aircraft operate.

Iran’s interest in anti-stealth radar networks is therefore easy to understand. Various news stories suggest that the F-35I Adir aircraft, the exclusive Israeli variant of the fifth-generation stealth Joint Strike Fighter, has successfully penetrated Iran’s airspace several times. The nature of open-source intelligence makes it difficult to ascertain with certainty whether these penetrations occurred. But one thing is certain: in 2018, Iran’s supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, sacked his air defense commander, General Farzad Ismail, and appointed Alireza Sabahifard to protect the country’s skies. This was an unexpected move by the supreme leader, sparking speculations that General Ismail was fired due to the Israeli actions within Iran. Since then, Iran has shown a growing appetite for anti-stealth capabilities.

It has also shown an interest in developing the capabilities to detect F-35s. Many experts suspect that the F-35’s geometrical design is detectable by very high frequency (VHF) radars. But due to their long wavelengths, VHF radars often lack the precision to guide a surface-to-air interceptor missile to a flying target on their own. This is why they are used to cue approximate sensor information to engagement radars. Aircraft with low observability such as the F-35 often stymie these engagement radars.

As a result, Russia’s air defense strategy to combat NATO’s tactical military aviation is centered on proliferating capable and overlapping VHF radars. By doing so, the Russians aim to provide adequate precision to their interceptor missiles and fighter aircraft, enabling them to more accurately target stealth platforms. Moreover, since legacy anti-radiation missiles are not optimized to home onto VHF radars, they are more resilient against SEAD missions.

In 2020, Russia’s state news agency, TASS, confirmed that the Islamic Republic had procured the Rezonans-NE, a VHF radar, in order to more accurately detect the F-35. Russia’s main arms export body, Rosoboronexport, advertises the Rezonans-NE as a robust solution against stealth air targets. Soon, Iran will be able to reap further rewards from the Kremlin’s reliance on Iranian capabilities in Ukraine, and shop for similar radars employed by the Russian military.

Iran’s Space Program and ICBM Proliferation Ambitions

Transactions between Iran and Russia meant to aid the countries’ space programs are also worth monitoring. Evidence suggests that Iran has conducted several recent launches that utilize space-related technologies.

Iran’s space program runs hand-in-hand with its work on intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), a critical weapons system optimized for nuclear combat payload delivery. The 2022 space cooperation agreement between Iran and Russia provided the IRGC with a stepping stone to the stratosphere. To develop a thorough understanding of this potential threat, one should be cognizant of Iran’s ambitions above and beyond the skies.

The IRGC’s advanced technology development node, known as the Self-Sufficiency Jihad Organization, started its solid-propellant space-launch vehicle (SLV) program in the 2000s. The father of Iran’s contemporary missile program, Hassan Moghaddam, was also the architect of the Islamic Republic’s space program. The IRGC’s space initiative pursued the goal of deploying a heavy-launch vehicle into geostationary orbit. In 2011, Moghaddam died in a suspicious explosion that set that program back years. Recently, Iran has picked up where Moghaddam left off.

Iran’s space program serves a dual-track agenda, providing a source of plausible deniability for its ICBM manufacturing goals, which Tehran aims to use as a global delivery deterrent for the nuclear warheads it hopes to possess. The technical details of the space vehicles Iran is attempting to produce help to inform an understanding of its ICBM- and nuclear-related ambitions.

While most SLVs are launched from static launchpads, the IRGC has been employing mobile launchers like the TELARs Iran uses for its ballistic missiles. More tellingly, Iran’s pronounced use of solid propellant for most of its SLVs is of high military utility but is less beneficial for conventional space-launch use.

In 2022, the space agencies of Iran and Russia signed a cooperation deal that further boosted Tehran’s ambitions. Perhaps as a result, in September 2023, Iran announced the successful launch of its Noor-3 satellite to a distance some 280 miles off the earth’s surface with the assistance of its Qased Space Launch Vehicle. Notably, the Qased SLV uses a technology that is also used in the development of intercontinental ballistic missiles.

January 2024 brought additional milestones for Iran’s clandestine space program. On January 20, Tehran announced the launch of the Soraya satellite. Iran employed the Ghaem-100 SLV, a critical asset that can also serve Tehran’s ICBM goals, to place this satellite into orbit. The Ghaem-100 shares some qualities with the Qased SLV, as both use the solid-fueled Salman motor as a second-stage propellant and another solid-fueled motor as the third. But the Ghaem-100 SLV’s first-stage motor, the Raafe, is a profound improvement over the Qased SLV’s liquid-fueled first-stage motor, which is derived from the North Korean missile technology used in Pyongyang’s Hwasong-7 ballistic missile. Following the Soraya launch, Iran further announced that it had successfully orbited three domestically produced satellites with the Simorgh SLV. The Simorgh is a two-stage, liquid-fueled SLV indigenous to the Islamic Republic. According to the US Defense Intelligence Agency, Iran’s Simorgh launches could serve as a proving ground for the ICBM program of the IRGC.

With Tehran moving forward with its space program and Moscow’s reliance on Iranian drone warfare systems growing, dangerous developments likely lie ahead. Iran could soon add ICBM-related items to its wish list in Russia.