Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 changed the Eurasian geopolitical landscape in a way not seen since the fall of the Soviet Union.1 Because of the immediate threat to Ukraine’s national survival, the United States rightly focused on providing Kyiv with rapid military and economic assistance. The US has been the coalescing force within the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, encouraging European nations to increase their defense spending and provide weapons to Ukraine in ways many foreign policy experts once thought to be impossible.

Because of support from the United States and its allies and partners, Ukraine has destroyed a significant portion of a top-tier US strategic adversary’s conventional military.2 According to a recently declassified intelligence assessment, 315,000 Russian soldiers—the equivalent of roughly 87 percent of Russia’s pre-invasion force—have been killed or wounded.3 More than 2,700 tanks have been taken out of service.4 Kyiv has liberated 54 percent of the territory Russia has captured since February 2022.5 And the Ukrainians have forced some of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet to retreat from its headquarters in occupied Crimea to the Russian coastal city of Novorossiysk.

As the war enters its third year, American policymakers should expand their diplomatic efforts beyond Kyiv. Russia’s shortcomings in Ukraine and Moscow’s waning influence in Eurasia give the US an opportunity to advance its national interest. To do so, Washington should conduct a diplomatic offensive across the region to maximize US influence, build new bilateral and multilateral ties, and restore or improve existing relationships.

Russia’s Waning Influence in Eurasia

So far, the United States has failed to work within or reform existing diplomatic formats or organizations to capitalize on Moscow’s waning influence. This is a mistake, as there are numerous examples of Eurasian nations pushing back on Moscow:

- Aside from Belarus, no member of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), whose charter contains a NATO-like collective defense clause, has spoken in favor of Russia’s war. Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko’s support is unsurprising. Vladimir Putin helped preserve Lukashenko’s rule following the controversial August 2020 Belarusian presidential election,6 and Belarus has effectively been a Russian protectorate since.

- Russia’s traditional partners and fellow CSTO members have not supported Moscow’s invasion in United Nations voting. CSTO members Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Armenia abstained from voting on the initial UN General Assembly resolution deploring Russia’s invasion of Ukraine “in the strongest terms.”7 Turkmenistan and former CSTO member Uzbekistan declined to respond entirely. And in May 2023, CSTO members Kazakhstan and Armenia voted in favor of a UN resolution that labeled Russia the aggressor against Georgia and Ukraine.8

- Onstage alongside Putin at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum in June 2022, Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev asserted that his country had no intention of recognizing Russia’s annexation of Luhansk or Donetsk.9

- Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has sounded alarm bells about Russia’s inability to fulfill its security guarantees in the CSTO.10

- In the aftermath of the Second Karabakh War, Russia was unable or unwilling to enforce the terms of the November 2020 ceasefire agreement it helped broker (namely, that Armenia would withdraw its forces from Karabakh and open regional transit corridors through its territory).

- In September 2023, Russian peacekeepers based in Karabakh did nothing as the Azerbaijani military took back all the territory it had lost to Armenia in the 1990s.11 This was a catastrophe for Russia’s standing in the South Caucasus.

- An emerging Turkic cohesion is challenging Russian influence. Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan publicly supported their fellow Organization of Turkic States (OTS) member Azerbaijan against Armenia in the recent conflict. This demonstrates Astana and Bishkek’s allegiance to the OTS over the Moscow-backed CSTO, of which Armenia is a member.

- Kazakhstan’s Tokayev assured German Chancellor Olaf Scholz that Kazakhstan will comply with Western sanctions imposed over Russia’s war on Ukraine and will not help Russia evade the sanctions regime.12

- Some Eurasian nations have broken with Moscow on the Israel-Hamas war. On October 16, Russia led an unsuccessful attempt to adopt a resolution on the UN Security Council that neglected to name and condemn Hamas.13 On October 17, Kazakhstan released a statement explicitly naming and condemning Hamas.14

Diplomatic Offensive

Many countries across Eurasia—especially the Central Asian republics—pursue a foreign policy of balancing between regional and global powers. This approach, when taken responsibly and effectively, encourages regional stability, which benefits US interests. Therefore, US diplomats should not present foreign policy in Eurasia as a zero-sum game with Washington pitted against Moscow or Beijing. The US should pursue policies that make balancing easier for countries across the region.

But after witnessing Russia’s many setbacks in Ukraine, numerous leaders from across the region have expressed a desire to increase ties with the West. It would be wise for the United States to answer this call, and Washington could utilize and reform existing regional formats and organizations to do so.

Below are 10 diplomatic initiatives the United States could take to enhance its influence across Eurasia, strengthen relations with key allies and partners, build new relations with multilateral or regional organizations, and undermine Russian influence.

1. Revitalize US engagement with the Organization for Democracy and Economic Development–GUAM (Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, and Moldova).

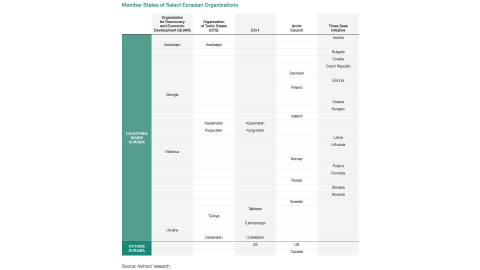

Background. The Organization for Democracy and Economic Development–GUAM, commonly referred to as GUAM, is a regional bloc that encourages economic, trade, cultural, and diplomatic cooperation between Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, and Moldova (see map 1). It was founded in 1997 and is headquartered in Ukraine.

Currently, all four nations have Russian troops on their territory—and all four want the Russians to leave.

Current situation. Territorial integrity has been a priority for the organization. GUAM strongly condemned Russia’s invasions of Ukraine and Georgia, Armenia’s occupation of the Karabakh region of Azerbaijan, and Russia’s ongoing military presence in Moldova’s Transnistria region. In recent years, GUAM has emphasized the advancement of free trade and transit connections in the region.

What needs to be done. Washington should consider how regional organizations like GUAM can help advance its national interest and build relations where US and regional interests overlap. The last US-GUAM meeting at the foreign minister level took place in 2017.15 Secretary of State Antony Blinken should immediately request a US-GUAM summit in Washington to explore ways to boost cooperation.

2. Engage with the Organization of Turkic States.

Background. The OTS began as the Turkic Council in 2009 at a meeting between the four founding members—Türkiye, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Azerbaijan (see map 2). The original idea behind the initiative was to deepen the shared cultural, historical, and linguistic roots, and enhance economic and trade relations between the ethnically Turkic countries of Eurasia.

Uzbekistan joined as a full member in 2019. Turkmenistan, Hungary, and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (a de facto state recognized by only Türkiye) have joined as observers. Other countries with sizeable Turkic minorities, such as Moldova (the Gagauz people) and Ukraine (the Crimean Tatars), have expressed interest in joining the OTS as observers.

Current situation. In total, members and observers of the OTS account for roughly 158 million people across 4.24 million square kilometers (1.64 million square miles). Other than Türkiye, all members of the OTS were once part of imperial Russia and the Soviet Union.

Since regaining independence in the early 1990s, the countries of Central Asia, along with Azerbaijan in the South Caucasus, have tried shedding their centuries-old, Russian-enforced links to Slavic culture. Instead, OTS states seek to promote their Turkic roots, culture, and shared history.16There are also millions of people of Turkic ethnicity who live in non-OTS countries but are influenced by Turkish soft power through cinema, music, and television. Populations speaking some variation of a Turkic language reside from southeastern Europe to eastern China—and most places in between.17

The countries of the OTS represent a relatively small but increasingly important portion of the world’s economy and reside in a region rich in natural resources including oil, gas, and rare earth minerals. Some of the world’s most important transit routes and trade chokepoints, such as the Turkish Straits, the Middle Corridor, and the Ganja Gap, are within the territory of OTS member states.

What needs to be done. The US should tighten relations with the OTS as a confidence-building measure for US-Türkiye relations, which need improvement. At first, Washington should moderate its ambition and expectations of US engagement with the OTS. Relevant US officials should meet with their OTS counterparts to pave the way for a US-OTS meeting at the foreign minister level. Eventually, this could lead to a US-OTS summit.

3. Think creatively in Central Asia and transform the C5+1 into a C5+2.

Background. On one hand, Central Asia is proximate to many of the geopolitical problems that the US faces around the world: a resurgent Russia, an emboldened China, Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, and hotbeds of Islamist extremism (see map 3). On the other hand, Central Asia presents the US with many practical economic opportunities. The region’s oil and gas reserves could help reduce Europe’s dependence on Russia, and the countries of Central Asia also have a good record of counterterrorism cooperation with the US.

Too often, US relations with the Central Asian republics (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, a grouping referred to as the C5) were built around the single issue that was most relevant at the time. For example, in the early 1990s, US engagement in Central Asia was built around democracy promotion. In the late 1990s, the focus shifted to energy. After 9/11, the US focused almost exclusively on counterterrorism cooperation. And once America’s mission in Afghanistan began to wind down, Washington paid little attention at all to Central Asia.

Current situation. The main format for US engagement in Central Asia is the C5+1. The Obama administration started the C5+1 initiative in 2015 to create a multilateral format for the five Central Asian republics to build relations with the US, and the Trump and Biden administrations continued the platform. The initiative made news in 2023 when President Joe Biden met with all Central Asian presidents on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly High-Level Week,18 becoming the first president to meet with leaders from all five republics at the same time. But beyond this, US engagement in the region has been minimal.

What needs to be done. US–Central Asia relations are so minimal that initial progress will be easy. For example, Washington should implement the following measures:

- The US needs to organize more senior-level visits to the region.

- Each C5+1 meeting should include a C5+2 session that includes Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan is the gateway to Central Asia for the transatlantic community and shares many economic, cultural, and transit links to the region.

- The US urgently needs a new Central Asia strategy that reflects the new reality in the region after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan. In February 2020, the Trump administration published the first United States Strategy for Central Asia in half a decade. While the strategy was well received by both regional governments and policymakers in Washington at the time, it is significantly out of date. (For example, the strategy emphasizes Afghanistan’s role in the region.)

- The US should pursue policies to build confidence between Washington and the Central Asian states to lay the foundations for an enduring relationship. America should not continue the transactional approach it has taken to Central Asia since 9/11.

4. Accept the new geopolitical reality in the Arctic and design a new “Arctic Allies” format for cooperation.

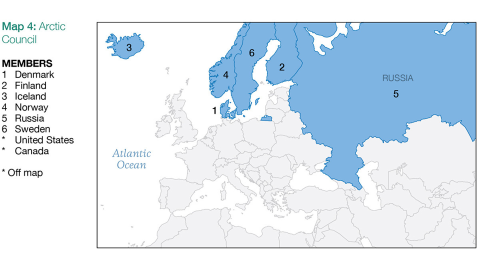

Background. The Arctic Council was founded in 1994 by the eight Arctic states (Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the US) to cooperate on nonmilitary issues in the region (see map 4). Of the Arctic states, all but Russia are either in NATO or, in the case of Sweden, will soon be.19 Over the years, the organization has cooperated on search-and-rescue operations, oil spill cleanup, and other issues. Even after Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, cooperation continued inside the council.

Current situation. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the Arctic Council has ceased functioning.20 No meetings take place, and day-to-day operations have stopped. In May 2022, Russia’s two-year-long chairmanship of the Arctic Council was transferred to Norway.

What needs to be done. It is inconceivable that the Arctic Council, in its current form, will function in any meaningful way while Russia continues its aggression against Ukraine. The seven other Arctic states need to start thinking about an alternative “Arctic Allies” format to continue cooperating in the region, even if on a temporary basis, until the Arctic Council can function normally again. The United States should lead this effort.

5. Engage more with the National Resistance Front (NRF) of Afghanistan.

Background. Since the US withdrew in August 2021, Afghanistan has been on a downward spiral. The country faces an acute humanitarian crisis, major food shortages, economic ruin, and an increasingly divided Taliban that is unable to govern effectively. Afghanistan is also becoming a haven for terrorists once again. More than a dozen different terrorist groups operate freely in Afghanistan. Some have global ambitions, while others are regionally focused. Most of these terrorist groups enjoy the hospitality and protection of the Taliban. The two most dangerous groups in Afghanistan that have grown since the Taliban’s takeover are al-Qaeda and the so-called Islamic State Khorasan.

Current situation. Soon after the Taliban captured Kabul, Ahmad Massoud Jr., son of the late Northern Alliance leader and Soviet resistance fighter Ahmad Shah Massoud, relocated to his family’s ancestral homeland in the Panjshir Valley to begin the NRF. The Panjshir Valley is a predominantly ethnic Tajik region located 60 miles northeast of Kabul and is famous for its ability to resist outside aggression. The NRF, though based in the Panjshir Valley, is active across the northern provinces and continues to be the only genuine, non-extremist armed opposition force against Taliban rule. Parallel to the armed struggle, Massoud and the NRF have been leading a diplomatic effort, commonly referred to as the Vienna Process, to align various anti-Taliban movements.21

Meanwhile, the Kremlin continues to embrace the Taliban. Russia’s ambassador to Afghanistan, Dmitry Zhirnov, praised the Taliban the day after it took Kabul in August 2021, calling the Taliban’s actions “good, positive, and businesslike.”22 While most of the world has isolated the Taliban, Moscow and Beijing continue to seek to strengthen its cooperation with the militant organization. In September 2022, the Kremlin completed a deal with the Taliban for Russia to supply Afghanistan with around 1 million tons of gasoline, 1 million tons of diesel, 500,000 tons of liquified petroleum gas (LPG), and 2 million tons of wheat annually.23 Recent reporting shows that the Taliban doubled purchases of Russian LPG from January–November 2023 compared to the previous year.24

What needs to be done. Many countries, including the US, currently regard the Taliban as the de facto government of Afghanistan. If the US is comfortable engaging with the Taliban, there is no reason it cannot do the same with the NRF. The US government should establish contact with members of the NRF to learn more about the group, its goals, and its needs. US Central Command could also assign a liaison officer to the NRF based out of the US Embassy in Dushanbe, Tajikistan.

Another consideration should be for the US to engage with the Vienna Process. If there is an Afghan future without the Taliban, the Vienna Process is the starting point. It is in America’s interest to send observers to the next gathering in Vienna to learn more about the different anti-Taliban groups.

6. Push for the construction of a trans-Caspian pipeline.

Background. Turkmenistan is home to the world’s fourth-largest natural gas reserves, but the country has made little effort to increase its exports of this valuable resource. For years, its main export market was Russia. This started to change in 2009, when China became the top destination after Beijing funded the construction of the Central Asia–China Gas Pipeline.25 In recent years, Turkmenistan has exported a small amount of gas to Iran and Uzbekistan. However, the Turkmenistan government has been unwilling to seek out new markets for its natural gas and attract much-needed foreign investment to boost its energy sector.

Current situation. With current technology, the only profitable way to move natural gas across the Caspian Sea is by pipeline. Liquified natural gas (LNG) tankers are too expensive for such a short distance. Fearing competition, Russia and Iran have pressured Central Asian countries not to build such a pipeline. But in recent years, owing to its growing confidence on the global stage, Azerbaijan has shown willingness to support the construction of a Caspian Sea pipeline. And in July, the Turkmenistan Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a surprising public statement signaling support for “the implementation of the trans-Caspian pipeline project.”26 A trans-Caspian pipeline could be a game-changer for European energy security. This would in turn make NATO more secure.

What needs to be done. The US played a key role in the South Caucasus and Caspian regions in the 1990s, pushing for major pipeline projects such as the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan Pipeline.27 The US should revisit this strategy and work closely with Europe to push for a trans-Caspian pipeline. This will require increased diplomatic engagement with Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan as part of a coordinated effort between the US, the European Union, and Türkiye. Over time, the group should explore the possibility of including Kazakh gas fields using interconnectors, since some Kazakh fields are in close enough proximity to be commercially viable. With positive signals coming from Ashgabat and Baku and decreased Russian and Iranian influence in the region, now is the time for a US push for a trans-Caspian pipeline.

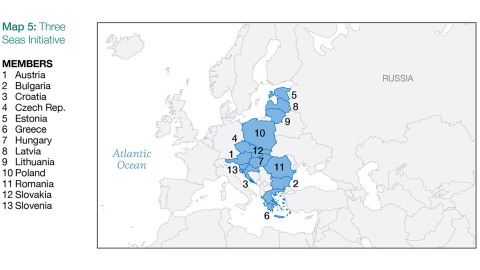

7. Revitalize US participation in the Three Seas Initiative.

Background. The Three Seas Initiative (3SI) was launched in 2016 to facilitate the development of energy and infrastructure ties among European nations situated between the Baltic, Adriatic, and Black Seas (see map 5). Most infrastructure in the region runs east to west, a legacy of the Cold War and the Warsaw Pact that still limits regional interconnectedness. The initiative aims to strengthen trade, infrastructure, energy, and political cooperation among these countries. The Trump administration strongly endorsed the 3SI, but the Biden administration has done little to advance the concept.

Current situation. The 3SI consists of Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Ukraine and Moldova are participating partners. The group accounts for almost one-third of the EU’s geographical size and has a population of more than 121 million people. While the countries of the 3SI account for less than 15 percent of the EU’s economy, they comprise “the fastest-growing region in terms of economy and GDP.”28 In 2019, Poland, Romania, and Estonia committed €620 million to establish the Three Seas Initiative Investment Fund (3SIIF) and encouraged other states and private investors to contribute to the fund. As of June 2022, it has grown to over €1.3 billion.29 There are currently about 90 different infrastructure projects in Eastern Europe being funded under the auspices of the 3SI.30

What needs to be done. Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 served as a wake-up call for the importance of the 3SI, particularly relating to ground transport and energy security in the region. In addition to encouraging investments into the 3SIIF, the US should promote five innovative proposals to get the 3SI ready for the future:

- Consider the role that the 3SI could have in the reconstruction of Ukraine. The 3SI could serve as the main platform for reconstruction in the same way the Marshall Plan did for Western Europe after the Second World War.

- Encourage 3SI countries to include more Western Balkan countries as members or participating partners.

- Encourage Finland to join the 3SI as a member and Georgia as a participating partner.

- Examine possibilities for civilian infrastructure projects that also help improve military mobility in Eastern Europe.

- Encourage the creation of a Three Seas Initiative Plus Caspian (3SI+C) platform to encourage Caspian and associated countries in the region to increase cooperation. Such a platform reflects these nations’ interdependence on matters of economic development and transportation, especially amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

8. Recognize the potential of the Middle Corridor for the economic and energy security of the region.

Background. Land-based trade and transit across Eurasia has been a crucial driver of geopolitics and economic development since the days of the Silk Road. Today, this east-west artery remains important. With international sanctions hitting Russia and Iran, many countries in the region are looking for better trade and transit routes between Europe and Asia. There is only one viable option for east-west trade on the Eurasian landmass to bypass Russia and Iran: the so-called Middle Corridor through the South Caucasus, over the Caspian Sea, and into Central Asia (see map 6).

Current Situation. Since Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Middle Corridor’s use has increased. For example, in 2022, container traffic through the Middle Corridor increased by one-third from the year before.31 For the first time, Kazakhstan is exporting uranium and crude oil to global markets through the Middle Corridor to bypass Russia.

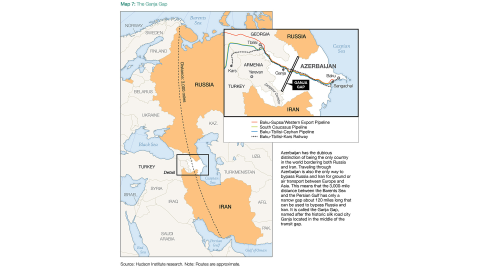

The Middle Corridor has an important chokepoint. Uniquely, it exists because of geopolitics and not topography. In the 3,000-mile span from the Barents Sea to the Persian Gulf, there is a 120-mile-long opening between Russia and Iran. This is called the Ganja Gap, named after the historic Silk Road city of Ganja in modern-day Azerbaijan (see map 7).

Currently, three major oil and gas pipelines that Europe depends on bypass Russia and Iran through the Ganja Gap.32 Not just Europe would be affected if these pipelines were disturbed. Israel gets 40 percent of its oil from Azerbaijan through the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan Pipeline. Fiber-optic cables linking Western Europe with the Caspian region also pass through the Ganja Gap. The second-longest European motorway, the E60, which connects Brest, France (on the Atlantic coast), with Irkeshtam, Kyrgyzstan (on the Chinese border), passes through the city of Ganja, as does the east-west rail link in the South Caucasus, the Baku–Tbilisi–Kars railway.

In addition to the Ganja Gap, there is another transport route that could boost regional trade and connectivity: the Zangezur Corridor. As part of the November 2020 ceasefire agreement that ended the Second Karabakh War, Armenia pledged to “guarantee the security of transport connections” between Azerbaijan proper and its autonomous Nakhchivan region via Armenia’s Syunik Province.33 The Zangezur Corridor would add resilience to the Middle Corridor. It could also boost the Armenian economy and integrate Armenia into regional transit and infrastructure projects for the first time in decades. Though Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has spoken positively about his desire to connect Armenia to the region as part of a “crossroads of peace” initiative, Yerevan has taken very little action.34

What needs to be done. As Russia and Iran escalate their reckless behavior, the Middle Corridor will become only more important. In the same way the US offered political support for regional projects like the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan Pipeline in the 1990s, Washington should support the construction of new regional transit and energy infrastructure along the Middle Corridor.

In the past, Armenians and Azerbaijanis traded with each other and lived peacefully. There is no telling how many billions of dollars in foreign direct investment have been denied to the South Caucasus because of the frozen conflict in Karabakh. Now that this matter is resolved, the US should encourage and, when possible, facilitate peace talks in pursuit of normalization between Armenia and Azerbaijan and between Armenia and Türkiye. An enduring peace would benefit the entire South Caucasus and the broader region.

In a recent address at the German Marshall Fund, Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs James O’Brien acknowledged that Central Asian states are looking for alternative trade routes that do not go through Russia or China.35 The Middle Corridor provides that alternative route, enabling goods to flow through the Caspian Sea into Azerbaijan, and then to Georgia, Armenia, Turkey, and eventually Europe. O’Brien signaled the United States’ willingness to work with the EU on bringing these alternative routes to fruition.36 The US would be wise to do so.

The US should also offer political support for the transit links that connect Armenia to the rest of the region. If there is genuine peace and the idea of a trans-Caspian pipeline is realized, regional governments could work to create a Turkmenistan–Azerbaijan–Armenia–Nakhchivan–Türkiye gas pipeline (TAANaT). The idea would not be to compete with the Southern Gas Corridor. Instead, such an ambitious project could help integrate the region, build trust among old adversaries, and aid Armenia’s energy issues. While the region is probably years away from the diplomatic conditions required for such a project, the US should start a discussion now on what is possible.

9. Develop information operations and outreach.

Background. The United States made strategic investments in information operations throughout the Second World War and the Cold War. But the budget for US international broadcasting has decreased dramatically in the last 30 years.37 However, networks such as Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL), Radio Free Asia (RFA), and Voice of America (VOA) have maintained their reputations for reliable journalism in Russia and elsewhere across Eurasia. If utilized well, they could provide the basis for a US information offensive in the Caucasus and Central Asia.

Current situation. Both Russia and China have poured money into offensive information campaigns in recent years. According to the US Department of State, Beijing spends billions of dollars a year on propaganda to manipulate and boost its image around the world.38 Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Moscow ramped up its spending on government-controlled mass media, with an estimated budget of $1.9 billion in 2022.39 The Kremlin also cracked down on independent journalists, arresting the Wall Street Journal’s Evan Gershkovich and RFE/RL’s Alsu Kurmasheva, both US citizens. Except for an RFE/RL budget increase of 15 percent in February 2022 (much of which was used to relocate the network’s journalists in Russia and Ukraine),40 US leaders have shown no urgency to strategically improve these resources or utilize them to increase US soft power in the region. The past two years have shown that the network, which reaches more than 40 million people per week, is indispensable for free and rigorous journalism.

What needs to be done. In addition to giving these agencies higher budgets to meet this new era of information warfare, the United States can find creative and effective ways to improve information operations across Eurasia. Though VOA operates in Russian, Armenian, Azerbaijani, and Georgian, it broadcasts in only one Central Asian language—Uzbek.41 Meanwhile, Sputnik, a main Russian state-owned news and broadcasting service, operates in Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Tajik, Uzbek, Armenian, Georgian, Azerbaijani, and Abkhaz, and Ossetian. The United States should consider hiring new journalists to work in Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Tajik, and Turkmen. This would also bring VOA’s operations up to par with RFE/RL, which services the official languages of all the C5 states.

Washington should also consider creating an RFE/RL service in another Turkic language: Uyghur. More than 1 million ethnic Uyghurs currently reside in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. RFE/RL enjoys considerable reach in Central Asia. Bolstering services among this vulnerable population—often a target of the Chinese Communist Party’s transnational repression—would be a worthy investment.

10. Urge increased American presence on the ground.

Background. In the past two decades, there has been a lack of high-level US engagement across Eurasia. No sitting American president has visited Armenia, Azerbaijan, any of the five Central Asian republics, or Moldova. Visits to the region by cabinet-level officials also remain infrequent.

Current situation. Before President Biden arrived in Ukraine in 2023, the last American president to visit Kyiv was George W. Bush in 2008.42 Bush was also the last US president to visit Georgia, in 2005.43

Secretaries of State John Kerry, Mike Pompeo, and Antony Blinken each made only one visit to Central Asia.44 The last US secretary of state to visit Georgia was Mike Pompeo during the lame duck period in November 2020.45 The last secretary of state to visit Armenia or Azerbaijan was Hillary Clinton in 2012.46

The late Donald Rumsfeld was the last secretary of defense to visit Central Asia, in 2006.47 No defense secretary has visited the South Caucasus since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The last was Lloyd Austin, who made an October 2021 visit to Georgia.48 The last time a secretary of defense visited Azerbaijan was Bob Gates in 2010,49 and no secretary of defense has visited Armenia since Donald Rumsfeld in 2001.50

What needs to be done. In addition to committing to more senior-level visits, the US should consider establishing a presence—whether in the form of a consulate general, consular agency, or other permanent outpost—in several strategic locations in the region:

- Ganja, Azerbaijan. Ganja is Azerbaijan’s second-largest city and is strategically located on one of the most important trade chokepoints on the Eurasian landmass, the Ganja Gap.

- Batumi, Georgia. Batumi is Georgia’s second-largest city and is strategically located on the Black Sea. The US established its first diplomatic presence in Georgia when it opened a consulate in this city. In 1915, during the early stages of the First World War when an Ottoman invasion threatened Batumi, the US moved its consulate to Tbilisi.51 A diplomatic presence in Batumi would raise America’s profile and give the US government a depth of situational awareness in the region that would not be possible otherwise.

- Tórshavn, Faroe Islands. The Faroe Islands is an autonomous constituent country of the Kingdom of Denmark located in the North Atlantic. Like Greenland, the Faroe Islands has sovereignty over most policy areas, with the major exceptions being foreign affairs, defense, and monetary policy, all of which are still controlled by Copenhagen. As Arctic issues become more important, the Faroe Islands’ geopolitical significance increases.

- Svalbard, Norway. Norway’s Svalbard Archipelago is a strategically important territory in the Arctic, approximately 600 miles from the North Pole. Due to its remote location and unique environment, Svalbard is very attractive for scientific research. Under the 1920 Svalbard Treaty, the US has the right to use Svalbard for scientific research. In the past, the Department of Defense has conducted research there, and it should consider doing so again.

Conclusion

Russia is a top-tier adversary of the United States, and Washington should continue to prioritize arming, equipping, and training the Ukrainian military. The more weapons the US gives to Ukraine, the weaker Russia becomes across the broader region. But this weakness in Eurasia only matters if the US takes advantage of it.

America and its allies and partners have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to force the Kremlin back into its geopolitical box. To capitalize, the US should also make a broader diplomatic push across Eurasia.