Michael Tolkin is thinking about the end of things. The 65-year-old writer and director is finishing his latest novel, his fifth. “A North Korean virus designed to confuse the South Korean officer class gets loose and the world loses its memory,” says Tolkin. He doesn’t want to give too much away but suffice it to say that while the world doesn’t have to be recreated, it has to be re-explained. So much is forgotten. “The elite have a mythology committee to explain how the world as they see it was left to them,” says Tolkin. “And to come up with explanations for the puzzling symbols found in houses of worship.”

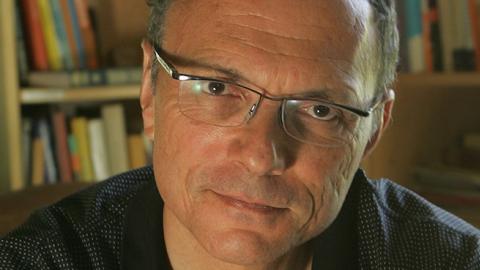

We’re sitting in a café in Los Angeles, where I’ve flown in for a few days to interview a number of West Coast Jewish writers and intellectuals to figure out something about our politics, or just our country. The West is America’s permanent metaphor for possibility and the limits of just how much things can change. This is one of the themes Tolkin explores in his work, including the TV show Ray Donovan, where Tolkin was one of the writers and a consulting producer. He wrote and directed one of the strangest and best American movies made in the last 25 years, The Rapture, and he’s one of our great, and way too underappreciated, contemporary novelists.

Tolkin’s father, Mel Tolkin, was the head writer for Your Show of Shows, without which the last half-century of sitcoms and comedy talk shows, from Seinfeld to Jon Stewart, could not exist. So, it shouldn’t have caught me by surprise when the athletic six-foot Tolkin shrank his body and launched into a Larry David-level impression of Bernie Sanders, whose first run at Congress Tolkin supported with a $10 donation. “Sanders is the guy on the park bench talking to the pigeons while he’s feeding them,” the novelist says. “And he was surprised that the pigeons were listening to him.”

Tolkin is a keen student of how power and storytelling are intertwined, often in ways that explore the darker places of the human condition. His most famous character is Griffin Mill, the studio executive in The Player--the novel that Robert Altman turned into a 1992 movie—who killed a writer. Many readers take The Player and the 2006 sequel The Return of the Player simply as satires of Hollywood vanity, mores, and deal-making. But Tolkin isn’t just dishing the inside dirt about the movie industry. Mill’s career path from studio executive, to Internet visionary and billionaire, to politician is an anthropology of moneyed American power. His interactions with his colleagues, the police, love interests, targets are premised on the idea that there is a story you must understand about this particular person in front of you, because failing to understand it could lose you everything. Anticipate what it takes to win—then disarm them, bully, and flatter.

The Bill Clinton who makes a cameo appearance in the 2006 sequel, The Return of the Player, is another classic Tolkin character. The real Clinton was a charming, intuitive guy who sharpened his skills in the bureaucratic, glad-handing worlds of local and then national politics. Tolkin’s Clinton is robed in movie glamor and says exactly the right thing to everyone, always. “He talks to the men about golf and the women about their parents’ diseases,” writes Tolkin. “Bill Clinton adds to everyone’s knowledge of themselves. For that, these men are willing to let him fuck their wives. Clinton is a genius, and Griffin knows what to ask him, which is, simply, everything.”

Tolkin’s Clinton makes a convincing case that “promiscuity can focus the senses.” “Very few of the people who make a dent on history can get enough of such wisdom from only one bed. And that’s what the American people understand, and in a moment of panic and weakness, I didn’t trust them.”

It’s hardly any wonder that this Clinton compares himself to King David, denied the honor of building the temple because he’d sent Uriah to die in battle so he could marry his wife Bathsheba. When the real Bill got in big public trouble, he didn’t talk his way out of it but famously took a flier on the verb “to be.” Tolkin’s Hollywood is Washington for people with really great sentences.

Clinton talks to Griffin about his wife. “I love her, I support her, and I’m proud of her,” he continues. “She is not a natural politician, which means she can’t easily make the usual pact of self-absorption with the people, who elect them.”

And that’s Hillary’s central flaw—not as a human, but as politician. She is incapable of telling a story about herself that resonates with the audience, the people out there, which is the only thing that matters in politics and the movies. Stories have to move real people sitting in the darkened theater, or on their couches at home. Character is a real thing, and it determines fate. The social fabric is delicate because it’s made of real people. Yet it’s become increasingly difficult to distinguish American political culture from dystopian fiction like The Hunger Games, where the capital is the home of a deracinated elite for whom the public is a prop for personal ambition, and mass politics is a spectator blood sport. Who’s bleeding now at which rally? Who’s the villain of the day?

“It’s all vanity,” says Tolkin about the current political debates. “All the screaming and arguments. The only political issue that matters is climate change. Everything else is midrash.”

It hardly comes as a surprise that a novelist and screenwriter who’s written two movies about different apocalypse scenarios--The Rapture and Deep Impact--believes that a natural phenomenon could lead to what is described in Deep Impact as an “extinction-level event.” There’s always a moment of radical rupture in Tolkin’s work, like Griffin Mill’s murder of David Kahane, with the after almost eclipsing the before. “The night before everything changed,” is how his 1993 novel Among the Dead begins. Tolkin’s typical time-line is warning, flood, exile, and sometimes redemption.

While this is the first time I’ve met Tolkin in person, we first became acquainted when I was at the Village Voice and published his article about The Turner Diaries, the racist and anti-Semitic 1978 novel about a race war, and Amalek, which came in the form of a response to an Alexander Cockburn article dripping with anti-Semitism. “That was my Jewish revivalism phase,” says Tolkin.

At the time he was interested in the work of Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik. As Tolkin later elaborated by email: “In the early ’90s, a reform rabbi suggested that I study Torah with a Modern Orthodox rabbi. I went to his shul every Thursday morning where I joined a small group. He’d been a student of Soloveitchik’s at Yeshiva University. I met a few other Orthodox rabbis who’d been there at the same time, and their Torah was exciting. They treated the patriarchs and matriarchs as troubled and human, no pedestals, and while personally stringent in their own practice, they were comfortable in the world. It was all part of millennial optimism, a hope of reconciliation.”

For three or four years, Tolkin explains, he stayed close to the Torah cycle, and less so now. “The Torah I learned from that generation was not repeated by the subsequent generation, or not by any that I met,” says Tolkin. He reads a number of Jewish writers, with Emmanuel Levinas it seems as a particular favorite, and quotes him. “I am responsible for your responsibility for me.” Otherwise, at this point it seems that Tolkin’s thinking about Jewish themes is mostly processed through American narratives, which makes him at once a consummately Jewish and a consummately American writer.

While Griffin Mill’s family life is a mess at the end of The Return of the Player, his ex-wife June argues that contrary to beliefs underlying current practice, marriage is a permanent bond. Thus, Griffin should take and his son and daughter under the same roof as his second wife and daughter. June says she got the idea when she dated a Mormon. It’s a very modern arrangement, except of course it’s not. It’s how Tolkin retells the story of the patriarchs, and Griffin, now running for office, is an especially flawed one.

In his 2003 book Under Radar, it’s again a murder that changes everything. Tom Levy is on vacation with his wife and two young daughters in Jamaica when he imagines another man has sexually humiliated one of the girls and he kills him. Tom goes to prison and then tells the story another man told him. The prisoners are rapt for days as it unfolds. “The prison is like a big yeshiva,” says Tolkin. “Everyone is doing midrash, and then they realize there’s no reason for them to be in prison.” The story and understanding of the story set the prisoners free, and then the government lets them go. “It’s about how you live after you’ve paid your debt,” says Tolkin. “It’s a very Jewish book.”

From Tolkin’s perspective, the most important book in American literature is Huckleberry Finn, and the worst villain of the novel is Tom Sawyer. “He knew Jim was free, but he exploited his freedom,” Tolkin explains. Tom misused his freedom to tell his own story, which means it can’t be a good story—or an American story.

Climate change, on the other hand, is a fundamentally American story. Or rather, as told by Michael Tolkin, it is a Jewish story in American dress, which means it offers the hope of redemption to mankind. The global warming story is a retelling of the flood myth, where every man is a potential Noah. If you take your life seriously, you can save yourself—and maybe the entire world. And this is why the story of impending doom resonates so powerfully with so much of the American public.

Tolkin wrote and directed The Rapture, the 1991 film about a woman, Sharon, who believes that the prophecy from the New Testament book Revelation is about to come true, and believers will be swept up into God’s bosom. She goes to the desert, despairs of God’s promise, and, in a play on Abraham’s near-sacrifice of Issac, resolves to kill her daughter and herself so that they may be reunited in heaven with her husband. Sharon kills the girl, but cannot commit suicide, and so is put in jail.

And then the end of the world really does come to pass. In one of the most stunning sequences in American cinema, Tolkin portrays the four horses of the apocalypse, in a steady, somber gallop, and then the horn of Gabriel blowing. The prison bars fall, and Sharon is free. Sharon uses her freedom to reject a God who’d let her kill her daughter. As the young girl pleads with her mother to forgive God, the darkness of eternity descends.

The account of the rapture is a central story for many American evangelicals, and Tolkin uses it to tell a story about, among other things, the Holocaust. There really is a God, and he let this happen. What part of his plan can this horror possibly fulfill?

The mainstream tradition of American Jewish literature is essentially a series of strong variations on a story about ethnic immigrants or their progeny struggling to make it in America or to prove they have. The paradox of course is that the crisis, or the wound, is so specific that the deeper the yearning for assimilation the further they are from shore.

Tolkin, on the other hand, draws on the energies of Judaism to turn Jewish experience outward and has given it American names. His apocalypses, like global warming, are, in a sense, optimistic accounts of a collective fate that we can control through right action. They are American accounts, premised on human freedom. If you take the promise of freedom seriously, you can save yourself. Maybe it’s America that will save you.