Executive Summary

For more than 80 years, Australia has relied upon its isolation and peaceful relations to protect its interests. But technology proliferation and a multipolar environment have created conditions that encourage revisionist governments to use military force in pursuit of territory and influence. The Australian Defence Force (ADF) therefore needs to be able to defend the homeland again.

In its most recent defense strategy, the Australian Department of Defence (ADoD) argued that it would pursue a strategy of denial to deter aggression. However, the ADF lacks the size or capabilities to implement this strategy under realistic budget and personnel constraints. Potential aggressors will likely deploy larger forces than the ADF and view denial as out of reach for Canberra.

Outright denial may not be feasible, but the ADF could deter aggression through a strategy of cost imposition that would threaten an attacker with the prospect of unacceptable losses or delay. This approach is especially advantageous for Australia, which is unlikely to be an essential or existential interest for an aggressor. An attack on Australia will likely seek to coerce Australia regarding economic or security policy or keep ADF forces occupied during military actions against other countries in the region. If an aggressor believes that operations against Australia would lead to unacceptably high losses or protraction, they could pursue other paths to their objective without reputational risk.

The challenge with a cost-imposition strategy is understanding which avenues of attack the aggressor is considering and what costs will be unacceptable. Canberra will need a campaign that uses signaling and operations to help policymakers estimate enemy leaders’ risk tolerance while in parallel establishing a defensive posture that can guard the country’s northern approaches.

The current ADF is not well-suited to implement either of these tasks. While it can effectively protect Australia from attacks in limited geographic areas, the ADF’s relatively small number of multimission ships, aircraft, and ground formations cannot address all the most likely avenues of attack. The ADF also has too few crewed multimission ships and aircraft to posture or adapt in novel or unexpected ways that could elicit responses that reveal adversary leaders’ risk tolerances.

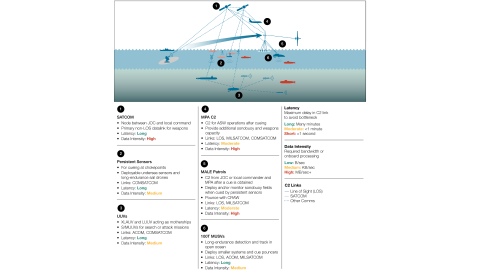

This study used a series of tabletop exercises (TTXs) to develop operational concepts that could deter conflict and defend Australia within the ADF’s fiscal and personnel limits. These concepts relied predominantly on uncrewed systems organized into hedge forces that conduct distant anti-submarine warfare, offensive counter-air operations, and anti-surface warfare to prevent threats from approaching Australian territory during conflict. Crewed ships and aircraft that are the bulk of today’s ADF would focus on peacetime responses and acting as a last line of defense in war.

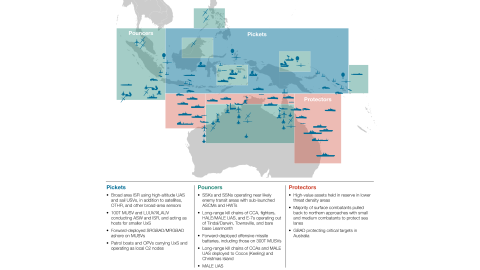

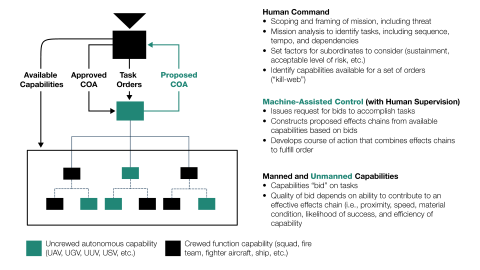

To support these concepts, teams in the TTXs developed a posture that organized the ADF into pickets, pouncers, and protectors as shown in figure ES.1. Uncrewed pickets detect and respond to threats; a mix of crewed and uncrewed pouncers delay or stop threats; and crewed protectors surge to augment pouncers or defend high-priority locations such as cities or military installations.

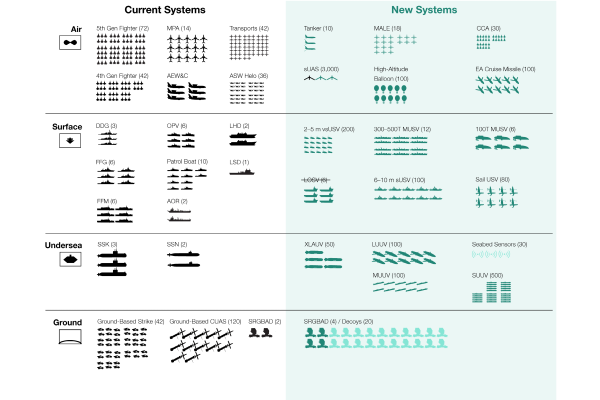

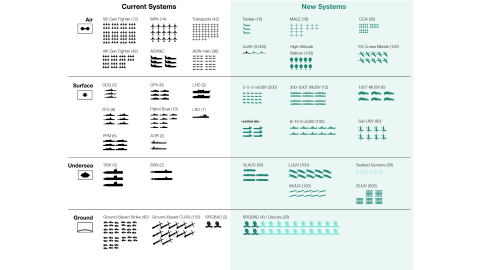

This study translates the concepts and posture developed during TTXs into a new force design that could sustain a deterrence campaign, summarized in figure ES.2. This design is affordable, assuming that the ADoD can redistribute the AUD 12.8 billion it earmarked for uncrewed systems between 2025 and 2035 to a new combination of crewed and uncrewed systems.

The force design only proposes modest changes in crewed units. Fiscal and industrial base constraints preclude growing crewed forces substantially while economic concerns prevent eliminating larger programs, such as in shipbuilding, that provide sizable employment. As shown in figure ES.2, the force design eliminates the Large Optionally Crewed Surface Vessel and adds short-range ground-based air defenses and aerial refueling aircraft.

The proposed force design makes almost all of its changes to the uncrewed system portfolio, primarily because they offer the scale and adaptability to address the ADF’s need for a distributed force that can defend the northern approaches while mounting a deterrence campaign against likely opponents.

Australia needs a new, more realistic defense strategy and a rebalanced force design to implement it. The strategy of cost imposition proposed by this study would seek to deter aggression by increasing enemy losses in a conflict and raising the likelihood of protraction. Facing the prospect of an embarrassing inability to quickly bring Australia to heel, adversary leaders may forgo military action and choose other avenues to pursue their interests against Canberra.

Figure ES.2 Proposed Force Design

Source: Authors.

In addition to being affordable within the ADoD’s existing spending plans, the changes recommended by the force design are implementable largely through domestic manufacturing and assembly. Although the ADoD may initially need to purchase some uncrewed systems from suppliers in allied countries like the United States, it can quickly pivot to building them in Australia. In addition to promoting economic development, this approach would allow the ADF to draw on a common allied industrial base and supply chain.

Of course, this study’s proposed force design is probably not the exact right answer. Systems will require rigorous assessment and testing, and some concepts may prove too challenging to execute in practice. The concepts and programmatic recommendations of this report are intended to give force planners an idea of the challenges and opportunities in building the future force and the possibilities within the ADF’s likely fiscal and personnel limitations. While the ADF’s challenges are substantial, it can still field an effective force during the next decade. But to realize this vision, the Australian government will need to act now while budgets enable the ADF to embrace the potential in uncrewed systems and other new technologies.

1. A Strategy in Denial

Australia has enjoyed more than 80 years without an attack on its territory thanks to its isolation and lack of natural enemies. But the Lucky Country’s fortunes may be starting to turn. Technology proliferation and a multipolar environment have created conditions that encourage revisionist governments to use military force in pursuit of territory and influence.1

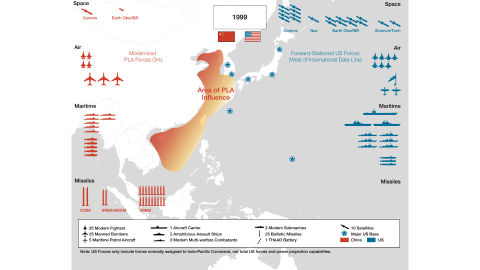

Australia has long depended on allies to bolster deterrence, but that may no longer be a reliable assumption. The US Department of War (DoW) considers China to be its pacing threat, but as shown in figure 1.1, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) outnumbers US and allied forces in the Western Pacific1 The US government is unlikely to devote substantial forces to defending Australia if such operations might reduce US deterrence against Beijing in Northeast Asia. And although the DoW plans to surge up to four times the capacity shown in figure 1.1 during a conflict, those forces will take weeks or months to arrive.3

Recent trends in US defense strategy and economic policy also undermine reassurance. Despite advocating an approach of peace through strength, the US Congress and the Trump administration are, like Australia’s government, planning for only modest increases in defense spending over the next decade.4

The Trump administration has further argued that US security guarantees to allies are contingent on them investing more in their own defense and rebalancing their trading relationships to buy more US exports.5 And although the Indo-Pacific remains the Pentagon’s priority theater, President Donald Trump and other national security officials have not committed to defending Taiwan against Chinese aggression.6

An adversary could also attempt to convince allied leaders that they should not come to Australia’s aid. In addition to economic or diplomatic coercion, an aggressor and its proxies could attack Japanese, British, or US territory and compel those governments to keep their forces home for domestic defense. For example, drone attacks, counter-shipping operations, or undersea cable disruptions could cause US leaders to divert troops to protect America’s military installations and economy. Under these conditions, Australia could find itself facing an attack essentially alone, with support only from forces the US has already deployed in the region.

Figure 1.1. Comparison of US Force Postures in 1999 and 2025

Source: Brian Everstine (@beverstine), “.@GenCQBrownJr shares this slide comparing US and China weapons platforms, but adds USAF Airmen are the 'force multiplier' that make the difference,” Twitter (now X), September 14, 2020, https://x.com/beverstine/status/1305512270571745282.

A Return to Self-Reliance

Until recently, Australia’s post–World War II military was largely designed to support overseas operations rather than to defend Australia. Under the early Cold War approach of forward defense, Australian Defence Force (ADF) units expected to combine with those of the United States and United Kingdom to counter Soviet aggression in Europe or Northeast Asia. The Australian government adopted more self-reliant strategies through the late 1970s and 1980s following the US withdrawal from Vietnam and reduced its presence in East Asia. However, as the 1987 Defence White Paper articulated, the Australian government viewed homeland attacks as a low-level concern and considered substantial threats to be a decade or more in the future.7

Subsequent white papers sustained these assumptions through the 2010s. The 2016 Defence White Paper was the first to highlight that the ADF should prioritize Australia’s northern approaches to protect the nation. But it assessed overall that “there is no more than a remote chance of a military attack on Australian territory by another country.”8 The 2020 Defence Strategic Update followed suit by prioritizing nonmilitary efforts to influence events in Australia’s region over defense or deterrence against potential attacks.9

Political leaders sometimes opposed the paradigm of focusing the military on overseas actions and relying on nonmilitary influence near home, arguing that the Australian Department of Defence (ADoD) should place greater emphasis on protecting Australian territory.10 However, substantial threats to the homeland did not materialize, and uniformed officials valued overseas operations as a way to remain proficient and justify continued defense investment.

The Australian government shifted course in its 2023 Defense Strategic Review (DSR). Whereas previous reviews emphasized cooperation and stability in the region, the DSR explicitly prioritized defense of Australian territory, especially the country’s northern approaches, against immediate and substantial threats. Moreover, the DSR identified that the ADF would pursue deterrence through denial, which would require capabilities that would prevent an aggressor from succeeding. Beyond deterring and defending against attacks on Australian territory, the DSR’s main objectives were protecting Australia’s global economic connections, contributing to collective regional security, and maintaining a rules-based global order.11

In conjunction with the DSR’s more muscular approach to defense policy, the Australian government pledged to spend more on defense. As described in the 2025–26 Portfolio Budget Statement (PBS), the government plans to increase defense spending by an average of 6 percent per year.12 This translates into about 3 percent of actual growth given Australia’s current inflation rate of about 2.6 percent.13 The 2025 landslide reelection of Labor Party leaders suggests this growth trajectory is likely to continue.14

But these relatively modest budget increases may not be enough to achieve the DSR’s objective of deterrence by denial. Revisionist nations continue to press ambitious—and generally extralegal—territorial claims. If an adversary dedicated a substantial portion of its forces against Australia, the ADF alone would be unable to protect Australian territory from air and missile attacks. And a relatively modest naval force would be sufficient to exploit Australia’s dependence on sea lanes by interdicting shipping going to and from the country’s ports.

With US support no longer assured, the Australian government will need to close the gap between the 2023 DSR’s aspirations and the ADF’s current capabilities. In the 2024 National Defence Strategy and Integrated Investment Program (IIP), the ADoD argues it will improve Australia’s defense mainly through the following efforts:

- Acquiring conventionally armed, nuclear-powered submarines through the Australia, United Kingdom, and United States agreement (AUKUS)

- Developing the ADF’s ability to precisely strike targets at longer range and manufacture munitions in Australia

- Improving the ADF’s ability to operate from Australia’s northern bases

- Improving the growth and retention of a highly skilled defense workforce

- Incorporating disruptive new technologies in close partnership with Australian industry

- Deepening diplomatic and defense partnerships with key partners in the Indo-Pacific15

These initiatives would strengthen the ADF and improve Australia’s ability to deter and defeat aggression. However, each line of effort could consume a substantial portion of the ADoD budget without realizing the ADoD’s strategy of denial. The ADF will need to reframe its strategy around achievable objectives and prioritize the initiatives and investments that can best achieve them.

Adopting a Cost-Imposition Strategy

The goal of deterrence by denial, which the 2023 DSR and 2024 NDS advanced, is a classic military strategy in which the defender prevents an attacker from realizing the benefits of its aggression.16 In most interpretations, a military pursuing a strategy of deterrence by denial would mount a defense that could credibly prevent an attacker from succeeding.17 This approach creates vulnerabilities, as historical examples like France’s World War II Maginot Line demonstrate. Unless the defending military is the dominant force, it will need to devote most of its capabilities to a so-called goal-line defense that could stop an offensive from reaching its objective. As in the World War II case, the attacker could circumvent a goal-line defense using new operational concepts or technologies. Or, in the case of Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, the aggressor could achieve many of its objectives by operating in the gray zone short of war.18

The US strategy for defending Taiwan reflects this interpretation of deterrence by denial. Taiwanese and US forces would counter a PLA invasion of the island by using uncrewed systems (UxS) and Taiwanese troops along the Taiwan Strait, coupled with long-range fires from US ships and aircraft in the region. If the two countries organized and orchestrated this approach effectively, it could prevent PLA forces from gaining a lodgment on the island or landing enough troops ashore to succeed.19 However, as recent operations by People’s Republic of China (PRC) maritime forces show, this goal-line defense does not address other scenarios like a blockade. It also allows the PRC to continue its gray-zone harassment of Taiwan.20

Another interpretation of deterrence by denial is that the defender—or the defender’s allies—will reverse the attacker’s actions and thereby negate the benefits of the attack. This approach could work, but few historical cases highlight its effectiveness. For example, the history of both world wars and Operation Desert Storm suggests that the potential for a counteroffensive by the defender’s treaty allies, or even the presence of allied troops in the defended country, may not dissuade a determined aggressor.21

The difficulty of implementing deterrence by denial led the United States and Soviet Union during the Cold War to eventually adopt a strategy of deterrence by punishment. Each nation reserved the right to use nuclear weapons if its government was imperiled or it was at risk of losing a military confrontation. This strategy certainly contributed to the lack of major conflict between the US and USSR during the Cold War, and it probably constrains the scale of confrontations today between nuclear-armed Pakistan, India, and China.22

Deterrence by punishment was likely effective in preventing major-power war because each side could credibly threaten existential nuclear attacks on its opponent. However, this strategy has failed to prevent smaller conflicts in which neither side, or only one side, possessed nuclear weapons. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 proceeded even though the US and its allies both threatened and realized economic and diplomatic sanctions that subsequently damaged Russia’s economy.23 PRC forces have skirmished with Philippine Coast Guard and Navy units although the Republic of the Philippines is a US treaty ally.24 And Iran directly or through its proxies has attacked Israel and US forces multiple times during 2023–25 although Israel is reportedly a nuclear-armed state.25

For Australia, deterrence by punishment is probably not an option. As a middle power, it lacks the economic heft to threaten sufficient sanctions or trade constraints to influence opposing leaders. And with a relatively small, conventionally armed military, Australia is unlikely to exact enough damage on an opponent to deter its leaders, even after Canberra obtains nuclear submarines under the AUKUS agreement.

But the ADoD’s stated strategy of deterrence by denial may also be out of reach. If the ADF were able to mobilize and position forces in time, it could prevent an adversary from seizing outlying territories, like the Christmas or Cocos Islands, and stop landings on Australia’s mainland. But the ADF’s current force lacks the capacity and persistence to sustain these operations or conduct them in multiple locations.

Aggressors could also attack Australia to coerce Canberra regarding trade and economic policies or dissuade Australian leaders from supporting allies or partners in conflicts across the Western Pacific or Indian Oceans. In support of coercion, an opponent could mount air strikes on northern Australia, assaults on shipping, or cyber and EW operations against Australian defense and commerce. The ADF will be hard-pressed to prevent these attacks from succeeding.

Outright denial may not be feasible, but the ADoD could deter aggression by reframing its goal as cost imposition. In this strategy, the defender increases the aggressor’s difficulty in achieving its goals. Facing the prospect of unacceptable losses or delay in accomplishing an operation, the aggressor chooses another path or waits for a better opportunity to emerge.26

Some proponents of deterrence by denial argue that deterrence by cost imposition is just a lesser included case of denial. Under this theory, a defender that cannot render an attack infeasible could still deter an attack by making it difficult enough.27 This is flawed reasoning. Denial is a binary condition—the action is either feasible or infeasible. But for a military to deter through not-quite-denial requires understanding what the aggressor considers “too difficult.”

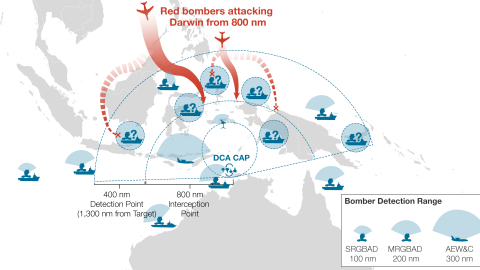

Consider the case of Australia. As a middle power, it lacks the resources to deny more than one (or maybe any) of the realistic paths available to an opposing military. For example, the ADF would need to substantially grow its current fleet of fighters, aerial refueling tankers, and airborne early warning and control (AEW&C) aircraft to deny an attack on Australia using bombers. That investment in equipment and personnel would prevent Australia from expanding or improving other elements of the ADF. A similar dynamic would occur when countering other threats, like submarines, surface combatants, or ballistic missiles. As a result, in each case the attacker would lose one option while other courses of action would become easier to execute.

In contrast to attempting denial, a military applying a strategy of cost imposition would focus its efforts on the scale and type of defenses that would create unacceptable losses or delay for the aggressor. A middle-power defender like Australia could stretch its modest pool of funding and personnel across the most likely forms of aggression by mounting sufficient defenses in each mission. For example, the ADF could complicate bomber attacks enough to make the mission too impractical for adversary leaders by using real and decoy air-defense systems at sea around the Indonesian archipelago.

The challenge with a cost-imposition strategy is understanding which avenues of attack the aggressor is considering and what costs will be unacceptable. A strategy of denial relies on the aggressor calculating that an attack cannot succeed based on the defender’s posture, demonstrations, or statements. A strategy of cost imposition requires the defender to predict the level and type of protection sufficient to dissuade the aggressor. But as recent conflicts in Ukraine or Kashmir show, defenders often underestimate the costs an aggressor is willing to accept in pursuit of an objective.28

One advantage of adopting a cost-imposition strategy is that likely aggressors will not consider conflict against Australia as a core interest. The stakes are existential for Russia in Ukraine; almost any cost is worth bearing if the alternative is collapse of the regime or the country. A country or non-state group will likely intend for an attack on Australia to coerce leaders in Canberra regarding economic or security policy, or keep ADF forces occupied during military actions against other countries in the region. If the losses or protraction of operations against Australia seem too high, the aggressor can pursue other paths to its objective without reputational risk.

The Cost-Imposition Campaign

The Australian government will need to build a feedback mechanism to better estimate the costs an aggressor is willing to accept in aggression against Australia. But the ADoD cannot wait for that analysis to begin attempting deterrence by cost imposition. It will need to pursue both initiatives in parallel—establishing the posture, concepts, and capabilities to counter the most likely attacks while using those efforts to elicit responses from potential aggressors that suggest their risk tolerance and cost thresholds.

A previous Hudson Institute study by Bryan Clark and Dan Patt describes this approach.29 Consistent with the ADF concept of integrated campaigning, deterrence by cost imposition requires a long-term, interactive process of messaging, fielding new capabilities, posture, and exercises designed to generate unguarded responses from a potential aggressor. The campaign would need to incorporate all instruments of national power, but this study will focus on the military’s role in fielding and operating a force that can support the overall campaign.30

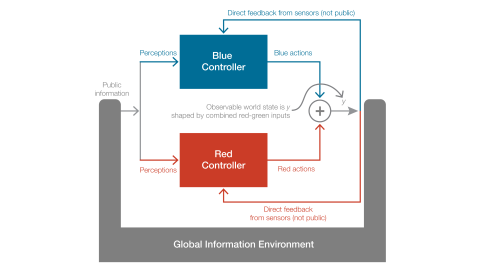

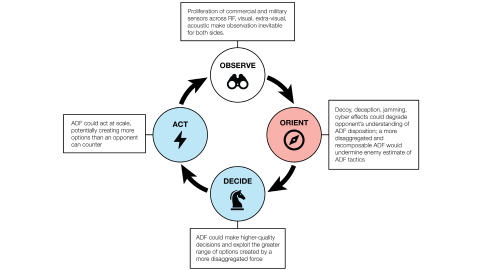

The campaign assessment process is shown in figure 1.2. Using the terms in ADF doctrine, the ADF (Blue) initially applies open-source and government intelligence information to understand the aggressor’s (Red) potential modes of attack and hypothesize what defenses may be most effective within the ADF’s capability and capacity limitations. The ADF then orchestrates public signals, such as exercises that gauge the aggressor’s concerns about the ADF’s operating areas or proficiency. The ADF can also generate effects, such as cyber or EW operations, designing them so that only the aggressor perceives them and so that they signal potential threats to the aggressor. The ADF would apply insights from analyzing the aggressor’s responses to develop the next set of public and private signals and sustain the campaign.31

To accurately estimate the aggressor’s risk tolerances, the defender will need to iteratively refine its actions based on previous responses. This requires a wide variety of potential new actions and capabilities. Moreover, the defender will need to conduct unexpected actions to elicit genuine, rather than pro forma, responses from the aggressor.

The ADF’s current force design will be unable to implement the deterrence campaign of figure 1.2 in two main ways. First, the ADF needs to mount an initial defense in the absence of feedback from potential aggressors. While it can effectively protect Australia from attacks in limited geographic areas, the ADF’s relatively small number of multimission ships, aircraft, and ground formations lacks the distribution to address all the most likely avenues of attack. And perhaps more importantly, the ADF is not recomposable enough to reorient against adversaries’ preferred forms of aggression when they are revealed.

Figure 1.2. An Assessment Process to Support Deterrence by Cost Imposition

Source: Authors.

Second, the ADF cannot provide sufficiently diverse or unexpected signals to develop an assessment of an aggressor’s priorities, pain points, and risk tolerances. The ADF’s crewed multimission ships and aircraft are too few in number to organize or posture in novel and unexpected ways and are not easily modifiable to incorporate new features or capabilities that generate surprising signals for the opponent.

The ADF will need a larger number of small platforms or units with only one or two functions to generate sufficient scale and adaptability to implement deterrence by cost imposition. This approach would bring two other benefits: First, it would reduce the consequences of any individual defensive engagement because the units involved would be smaller and predominantly uncrewed. Second, a more distributed and recomposable force design would enable the ADF to reallocate forces against threats as they materialize during combat against a larger opponent like the PLA.

Raising AUKUS’s Second Pillar

The ADF could use the AUKUS initiative to evolve its force design. In the near term, under AUKUS Pillar I, the allies will establish by 2027 a rotational force of up to five US and UK nuclear attack submarines (SSNs) operating from Australia’s west coast. Over the medium term, the ADoD will purchase up to three US Virginia-class SSNs starting in 2032. Over the long term, Australia and the UK will develop the SSN-AUKUS to replace the Royal Navy (RN) Astute-class SSNs and remaining Royal Australian Navy (RAN) Collins-class conventional submarines, which they will field in the 2040s.32

The allies have made steady progress along the “optimal pathway” of AUKUS Pillar I. Australian sailors and officers are already graduating from US and UK nuclear propulsion training pipelines and will join Royal Navy and US Navy SSN crews until Australia has its own SSNs.33 US SSNs have operated from HMAS Stirling in Western Australia and conducted maintenance at an Australian facility.34 And several US SSNs will visit Australia during 2025, with one completing a three-week maintenance period.35

Allied and Australian SSNs will surely improve the ADF’s ability to deter aggression. To attack Australia, an opponent would need to rely on naval forces or long-range missiles and aircraft. With unlimited submerged endurance and superior stealth, RAN SSNs could engage enemy ships well before they reach weapon range of Australia. And although SSNs may not be able to attack aircraft, they could strike the air bases that host them.

But SSNs are not a solution to all the potential threats facing Australia. An attacker could use unmarked ships to carry missiles and one-way attack drones within reach of Australian territory before RAN SSNs can interdict them. Several countries’ submarines are relatively quiet and could avoid RAN SSNs to conduct missile attacks against Australian territory. And as recent operations by Russia demonstrate, ballistic or hypersonic missiles could also reach Australia from an opponent’s protected interior.

The ADoD will need to raise AUKUS’s second pillar of emerging technologies to address the full range of enemy attack options and create a more distributed and recomposable force that can support a deterrence campaign. Most AUKUS Pillar II activity focuses on six technology areas, each with its own working group:

- Undersea capabilities

- Quantum technologies

- Artificial intelligence (AI) and autonomy

- Advanced cyber

- Hypersonic and counter-hypersonic capabilities

- Electromagnetic warfare36

While Pillar I is proceeding apace, the allies have made uneven progress in fielding new technologies under Pillar II. They moved most quickly on undersea capabilities, including integrating the UK Swordfish torpedo and new AI-enabled sonar algorithms on P-8A maritime patrol aircraft.37 The US and Australian navies have also conducted multiple rounds of experimentation with maritime autonomous systems, some of which they are incorporating into their forces.38

The allies have made less headway on other Pillar II technologies. For example, the ADoD and the Pentagon established the Hypersonic Flight Test and Experimentation (HyFliTE) Project Arrangement in 2024, more than three years after signing the AUKUS agreement.39 The allied nations also did not complete the first AUKUS Pillar II prize competition, focusing on EW, until late 2024.40 A second prize competition, focusing on undersea autonomy and communications, started in spring 2025.41

The allies’ modest results in AUKUS Pillar II capabilities beyond undersea systems are largely due to a lack of focus. The US military has a wide variety of investments relevant to AUKUS Pillar II technology areas and has shared many of those technologies with the other AUKUS allies. However, it has not adopted a formal program around any Australian or UK Pillar II technology efforts. As a result, UK Ministry of Defense and ADoD AUKUS Pillar II projects generally fall short of fieldable military capabilities.

The AUKUS allies recently established the International Joint Requirements Oversight Council (I-JROC) to ensure they allocate funding and leadership attention to the most important AUKUS Pillar II programs. Modeled on the DoW’s JROC, the I-JROC includes the vice chiefs of defense of each AUKUS ally, who lead their respective militaries’ force design activities.42

However, a potential limitation of the I-JROC model is that each ally has different operational problems to address. Australia’s challenges center on extended-range homeland defense, whereas the US military is mainly an expeditionary force designed to project power in defense of allies. The UK’s defense priorities encompass both mission sets due to air and naval threats from Russia and the need to defend UK interests and citizens in the Mediterranean Sea and Indian Ocean.

Given the allies’ lack of focus in AUKUS Pillar II, the ADoD should prioritize its own defense technology efforts to address the key operational problems in implementing deterrence by cost imposition. For example, the ADF faces the following operational problems in its three more important homeland defense missions:

- Anti-surface warfare (ASUW). Crewed aircraft, ships, and SSNs could conduct most ASUW operations around Australia thanks to an uncontested air and surface environment. However, the ADF’s relatively small fighter and surface combatant fleets would be unable to cover the full reach of Australia’s northern approaches and sea-lanes. They may also need third-party targeting from uncrewed systems anywhere from the seabed to space to update weapons in transit.

- Integrated air and missile defense (IAMD). Enemy fighters or bombers could attack northern Australia using cruise missiles from outside the range of land-based Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) fighters. With aerial refueling, RAAF aircraft could engage small numbers of bombers before they launch cruise missiles, but only in narrow geographic areas. And the RAN’s three air-defense destroyers may be insufficient to protect critical Australian targets from ballistic missiles or boost-glide hypersonic weapons.

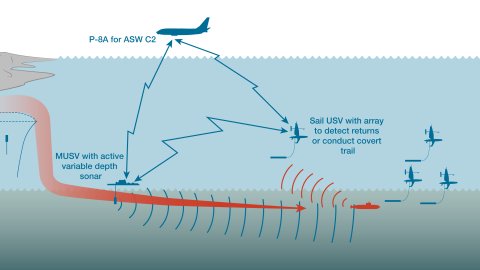

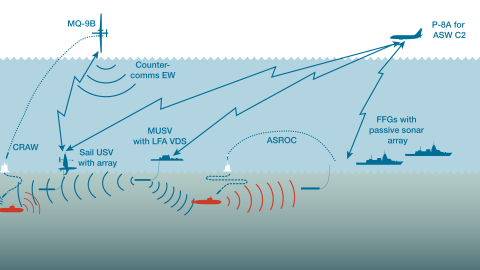

- Anti-submarine warfare (ASW). As with ASUW, the permissive air and surface environment around Australia would allow ADF ships and aircraft to conduct ASW. However, the ADF lacks the capacity to cover all relevant areas with today’s crewed ships and aircraft. The relatively short ranges of most ADF ASW sensors and weapons exacerbate this problem.

The ADoD could apply the full range of AUKUS Pillar II technologies to these gaps. For example, it could apply new undersea capabilities to ASUW and ASW sensing and engagement gaps and use hypersonic weapons against enemy surface forces or bases from which adversary bombers operate. It will need hypersonic defenses to protect Australian territory from advanced missile attack. Most importantly, UxS and AI could offer Australia’s military the scale and adaptability it needs to deter and defeat aggression.

A Changing Value Proposition

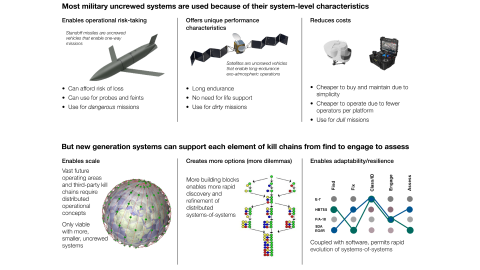

Australia is not alone in pursuing uncrewed and autonomous systems. Militaries around the world are quickly adopting UxS as a substantial portion of their forces. This trend accelerated during the last five years due to rising compensation costs, the availability of militarily relevant commercial technology, and the demonstrated success of drones during the Russia-Ukraine War and Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping. These forces have reshaped themselves around UxS as the primary battlefield weapon, confining traditional cruise and ballistic missiles and aircraft to niche missions.43

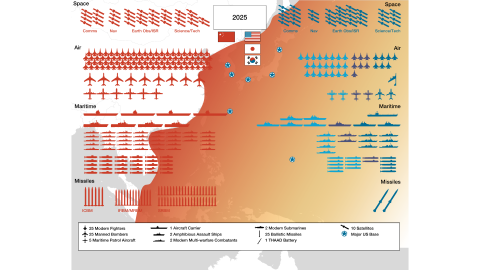

The value proposition of UxS is changing, as shown in figure 1.3. Uncrewed systems are now used for every link in military kill chains instead of being treated as adjuncts to the traditional crewed force for “dirty, dull, and dangerous” missions. Humans remain in the loop to make decisions about which targets to attack, but they increasingly rely on UxS to make their own decisions about how to reach a target, precisely when to attack it, and which effects to use in prosecuting the attack.44

This changing value proposition allows militaries to do more than simply lower risk to humans or achieve greater reach and persistence. Because they can contribute to any link in the kill chain, UxS can dramatically increase a force’s scalability, complexity, and adaptability. The force that better exploits the new value proposition for UxS can create more dilemmas for opponents, which would need to prepare for a wider variety of potential threats.

Figure 1.3. The Changing Value Proposition for Uncrewed Systems

Source: Authors.

The ADF could also dramatically reduce future personnel requirements by adopting UxS to perform a larger portion of Australia’s military missions. Using automation, the ADF could reduce the crews needed for each ship, aircraft, or ground unit and improve the efficiency of support functions like logistics or administration. But crewed ships or aircraft require sustained upkeep even when at home base and need to operate regularly to keep their crews proficient.

Uncrewed systems offer a more effective way to reduce personnel needs compared to automation. A military can grow the number of UxS faster than the associated increase in the number of required personnel because a single operator and support crew can operate multiple vehicles simultaneously. When UxS are not needed, they can be stored with only minimal maintenance, and their operators can stay proficient using simulators.

A Path to Strategic Solvency

To its credit, the ADF’s plans incorporate UxS across each domain and in many cases treat its new autonomous systems as independent actors rather than merely adjuncts to crewed platforms and units. However, the planned number and mix of UxS in the ADF does not support Australia’s current strategy or a strategy of cost imposition. And other AUKUS Pillar II technologies, such as hypersonic attack and defense, will likely need more resources to protect Australia’s northern approaches.

This study will assess the security challenges facing Australia and propose an alternative path to achieve the ADoD’s goal of deterring and defeating aggression within realistic fiscal and personnel constraints. The next chapter will describe the study approach, which used a combination of tabletop exercises (TTXs) and interactive workshops to develop a proposed force design for the ADF in 2035. Chapters 3 and 4 will describe those assessments and proposed forces in detail, and Chapter 5 will provide conclusions and recommendations for the ADF.

2. Study Framework

Hudson Institute used a combination of TTXs, workshops, and academic research to assess ways the ADF could implement a strategy of deterrence by cost imposition within its fiscal and personnel constraints by the mid to late 2030s. The study framework was structured to address a set of research questions regarding ADF force design:

- What are the main strategic challenges facing Australia and the ADF in 2035–40?

- How should the ADoD equip and posture the ADF in 2035–40 to implement its strategy, considering realistic fiscal and personnel limitations?

- How should ADF units conduct warfighting operations in the mid-2030s to take advantage of emerging technologies?

- How could US military contributions impact the needed ADF force design?

The study assumed the main constraints on ADF force design would be funding and personnel. The AUKUS agreement would likely make almost all relevant allied technologies available to the ADF, and the combined allied industrial base would likely be able to deliver equipment and systems in quantities the ADoD could afford.

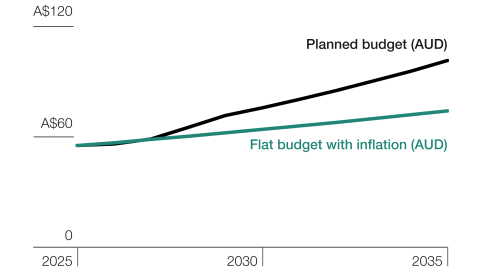

Budget

The study assumed ADoD budgets through 2035 will remain consistent with current Australian government plans. The ADoD’s planned budget as described in the 2025–26 PBS grows at an annual rate of about 3 percent above inflation from 2024–25 through 2028–29. The study assumed this 3 percent rate of real growth continues until 2035, as shown in figure 2.1. This assumption is likely to be optimistic, considering that the Australian government has not begun to grow defense spending in line with the 2024 NDS and IIP. It has deferred much of the decadal investment those documents describe to start in the late 2020s.45

Within the overall defense budget, the study assumed that funding for new capabilities would remain consistent with the 2024 IIP. In that document, the Australian government established a goal of AUD 330–430 billion for procurement and for research and development (R&D) during 2024–34. However, it has approved only about AUD 92 billion of that investment spending.46 The slow implementation of the 2024 NDS and IIP suggests the ADoD may not be able to achieve its planned total investment budget.

Figure 2.1. Assumed Spending Levels Used in the Study

Source: Authors, using ADoD data.47

The study assumed the ADoD can realistically reallocate only a portion of its planned investment funding to implement its proposed fleet design. For example, government investments in crewed ship construction provide essential employment and workforce training. Other investments—such as improvements to base, housing, or information technology infrastructure—are likely already at the minimum level to support current operations. These cannot be reduced without creating new vulnerabilities. And some investments, such as space and cyber capabilities, are classified, so this study cannot adequately assess or explain proposed changes.

To address these limitations, the study assumed that planned investment in UxS is the primary fiscal tradespace for a new fleet design. As described in chapter 1, uncrewed and autonomous systems will be the primary means to achieve the scale and adaptability ADoD needs to implement deterrence by cost imposition. Investments in crewed shipbuilding, cyber and space capabilities, and infrastructure will not be in the tradespace. The study proposed adjusting other planned investments, but on a limited basis that minimizes the need to analyze impacts on personnel and sustainment.

The 2024 IIP identifies a planned investment of about AUD 12.8 billion in UxS between 2025 and 2035. The government has approved only a fraction of this funding, but the study assumed it would eventually achieve this funding level. Of that, the study assumed the ADoD could devote about 70 percent, or AUD 8.5 billion, to UxS procurement, and the rest to R&D and fielding costs.

In general, the study assumed that reallocating investment would result in a commensurate realignment of personnel and sustainment spending to ensure the new capability mix is supported. It further assumed that the operations and support costs of the new capability mix will be within the planned spending on personnel and sustainment. This is a conservative assumption. As described in chapter 4, the proposed force design rebalances the ADF toward more uncrewed and autonomous systems and away from crewed platforms, which reduces the number of necessary personnel in the ADF and likely lowers sustainment costs relative to the current IIP plan.

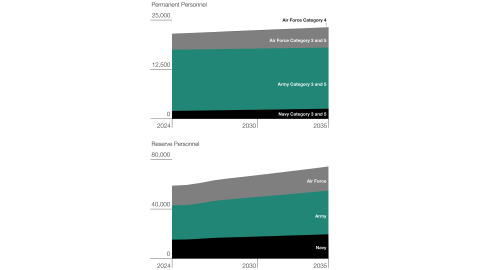

Personnel

The Australian government plans to grow the ADF to about 69,000 permanent uniformed personnel by the early 2030s and about 100,000 permanent uniformed and civilian personnel by 2040, according to the 2024 Defense Workforce Plan.48 The ADF would need to grow at about 2 percent per year to reach those levels. The study assumed personnel levels in the ADF will grow at that rate annually through 2035, as shown in figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2. Assumed Personnel Levels in the Study

Source: Authors, using ADoD data.49

Like the budget assumptions above, these personnel assumptions may be optimistic. The ADF has not met its recent recruiting targets, missing by 20 percent in 2024.50 The ADoD’s outsourcing of recruiting operations to a contractor is complicating its efforts to address this shortfall. The ADoD can penalize the contractor for failing to meet targets, but this is only retrospective and does not help fill today’s gaps in ships, aircraft squadrons, or ground formations.

Developing the 2035 Force Design

Within the budget and personnel constraints described above, the study used a series of TTXs and workshops to assess how the ADF force design should evolve between 2025 and 2035 to implement the ADoD’s strategy. Hudson Institute conducted two TTXs with a group of military officers and defense civilians from the US, Japanese, and Australian militaries, complemented by selected industry technical experts. The first TTX was held in Japan, and the second in Australia. Hudson Institute conducted workshops before each TTX to familiarize players with the capabilities to be used and after the TTX to discuss the TTXs’ implications for force design.

Scenario

The TTXs used a scenario set in 2035. In it, an ongoing conflict takes up all available US (Purple) and Japanese (Green) forces. As a result, they are unable to support Australia’s (Blue) homeland defense missions.

TTX Teams and Forces

The TTXs compared three potential future ADF force designs to assess a range of ways the ADoD could address future operational needs within its fiscal and personnel constraints. Hudson Institute based the number of crewed units in each force design, shown in table 2.1, on the 2024 IIP. The ADoD is unlikely to change its shipbuilding or aircraft production plans substantially due to the industrial base and economic impacts described above. Because analyzing such changes was unnecessary, Hudson Institute assigned each force design the same number and type of crewed units.

Table 2.1. Crewed Forces Assigned to Each Blue Team

|

Type |

Class |

TTX Inventory |

|

Nuclear Submarine |

Virginia-class SSN |

2 |

|

Conventional Submarine |

Collins-class SSK |

3 |

|

DDG |

Hobart-class DDG |

3 |

|

FFG |

Hunter-class frigates |

6 |

|

FFM |

Mogami-class frigates |

6 |

|

Patrol Boat |

Evolved Cape-class patrol boat |

10 |

|

Offshore Patrol Vessel |

Arafura-class patrol vessel |

6 |

|

OSV |

Large Optionally Uncrewed Vessel |

6 |

|

Tanker |

Supply-class replenishment oiler |

2 |

|

Assault Ship |

Canberra-class LHD |

2 |

|

Landing Ship |

LSD |

1 |

|

Watercraft |

Army watercraft |

24 |

|

Air Defense |

SRGBAD battery |

2 (24 launchers) |

|

Air Defense |

MRGBAD battery |

0 |

|

Air Defense |

CUAS system |

120 |

|

Long Ranged Ground Launch |

HIMARS |

42 |

|

Short/Medium Ranged Ground Launched |

Loitering Munition Battery |

50 |

|

Hypersonic Launcher |

Hypersonic Battery |

4 |

|

MPA |

P-8 |

12 |

|

AEW&C |

E-7 |

6 |

|

Land-Based Fighter |

F-35A |

72 |

|

Refueling Aircraft |

KC-30 MRTT |

7 |

|

Land-Based Fighter |

F-18F |

24 |

|

Land-Based EW |

EA-18G |

18 |

|

ASW Helicopter |

MH-60R |

36 |

|

Ground Attack Helicopter |

Apache |

29 |

|

Transport Helicopter |

Blackhawk |

40 |

|

Transport Helicopter |

Chinook |

14 |

|

Transport Aircraft |

C-17 |

8 |

|

Transport Aircraft |

C-130 |

24 |

|

Transport Aircraft |

C-27 |

10 |

Source: Authors.

Notes: AEW&C = airborne early warning and control, ASW = anti-ship warfare, CUAS = counter uncrewed aerial system, DDG = guided-missile destroyer, EW = electromagnetic warfare, FFG = frigate, FFM = multi-mission frigate, HIMARS = High Mobility Artillery Rocket System, LHD = landing helicopter dock, LSD = landing ship dock, MPA = maritime patrol aircraft, MRGBAD = medium-range ground-based air defense, MRTT = multi-role tanker transport, OSV = offshore support vessel, SRGBAD = short-range ground-based air defense, SSK = diesel-electric submarine.

Hudson Institute assigned each force design a different mix of UxS to assess which systems and associated operational concepts were most beneficial in addressing Australia’s future operational challenges. A different team played each force design, as described below:

- Blue Team 1. Large UxS: Emphasized multimission UxS with long endurance and organic weapons.

- Blue Team 2. Small Systems: Emphasized tactical, single-function UxS.

- Blue Team 3. Hybrid Force: Incorporated a mix of large and small UxS.

Hudson Institute constrained each UxS force list with the assumptions that funding for UxS would remain at about AUD 8.5 billion for procurement based on the 2024 IIP and that only about 7,500 personnel would be available for UxS operations, about half the new personnel added to the ADF from 2025 to 2035. Table 2.2 shows the UxS assigned to each Blue team.

Table 2.2. Uncrewed Systems Assigned to Each Team with Notional Examples

|

Domain |

Type |

Example |

Team 1 (Large) |

Team 2 (Small) |

Team 3 (Hybrid) |

|

Surface |

300T MUSV |

US Navy Ranger |

8 |

6 |

|

|

100T MUSV |

US Navy Sea Hunter |

15 |

10 |

||

|

6-12m sUSV |

US Navy CUSV |

325 |

200 |

||

|

2-5m sUSV |

Saronic Spyglass |

800 |

400 |

||

|

Sail sUSV |

Ocius Bluebottle |

100 |

90 |

||

|

Air |

HALE |

US Navy MQ-4 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

|

MALE |

JMSDF MQ-9B |

24 |

12 |

||

|

CCA |

Boeing Ghost Bat |

36 |

0 |

36 |

|

|

6’’ sUAS |

Anduril Altius-600 |

15,000 |

10,000 |

||

|

Undersea |

XLAUV |

Anduril Ghost Shark |

10 |

8 |

|

|

LUUV |

C2 Robotics Speartooth |

50 |

30 |

||

|

MUUV |

US Navy Razorback |

120 |

100 |

||

|

SUUV |

US Navy Lionfish |

630 |

500 |

Source: Authors.

Notes: These systems were chosen by Hudson Institute and are not reflective of ADF plans. CCA = collaborative combat aircraft, CUSV = common uncrewed surface vessel, HALE = high-altitude long endurance, LUUV = large uncrewed underwater vessel, MALE = medium-altitude long-endurance, MUSV = medium uncrewed surface vessel, MUUV = medium uncrewed underwater vessel, sUSV = small uncrewed surface vessel, SUUV = small uncrewed underwater vessel, XLAUV = extra-large autonomous underwater vessel.

A White cell comprising Hudson Institute personnel played the forces of other countries, whose actions were largely scripted in advance of the TTXs. Non-ADF forces did not interact with the Blue teams in the TTXs under the assumption that they focused on other operations. For example, the exercise assumed that the US force was attempting to break the blockade of Taiwan and that the Japanese force was defending Japan and attempting to close the First Island Chain across the Nansei Islands.

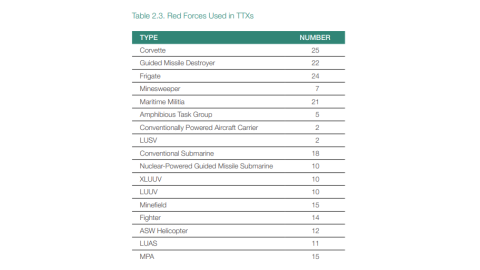

Three Red cells of two experts each played the aggressor force, with one cell opposing each Blue team. Hudson Institute scripted the Red forces’ actions but allowed each Red cell to deviate from the script when appropriate. The TTX scenario assigned each Red team the same forces, shown in table 2.3.

The Red force included only larger uncrewed systems, such as long-endurance large uncrewed air systems (LUASs), large uncrewed surface vessels (LUSVs), and larger uncrewed undersea vehicles (UUVs). The Red force would likely integrate small UxS with crewed units or larger UxS to carry them the long distances to Australia and coordinate their operations.

Table 2.3. Red Forces Used in TTXs

Source: Authors.

TTX Mechanics

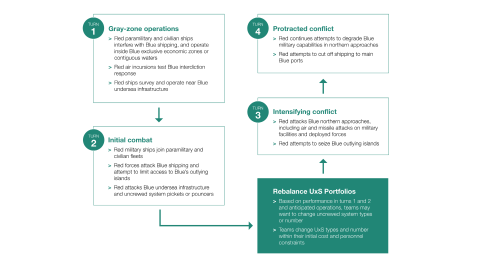

The TTXs used four main turns, shown in figure 2.3, to play through the scenario. It started with gray-zone actions against Blue, then escalated over nine months of game time through Red attacks on the Blue homeland. Teams were provided an opportunity to adjust their UxS portfolios midway through the TTXs based on insights from the first two turns.

Figure 2.3. TTX Methodology

Source: Authors.

Rules of engagement (ROE) changed during the TTXs consistent with the level of escalation. During Turn 1, Blue could not engage Red forces except in self-defense. This resulted in a protracted gray-zone operation between Red and Blue forces. The ROE changed in Turn 2 to also allow Blue forces to engage Red forces attacking shipping or uncrewed pouncers. And in Turn 3, Blue forces were allowed to engage Red anywhere because Red had begun attacks on Blue’s deployed forces and homeland.

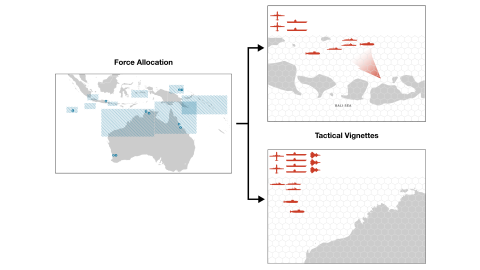

During each turn, Blue teams conducted two tasks, summarized in figure 2.4.

Force allocation. Each team allocated its entire available force across the missions and geographical areas they were concerned could be subject to Red attack.51 This task provided insights regarding the necessary number of each type of ship, aircraft, troop formation, or UxS. Teams used a physical chart and tokens to deliberate on their force allocation and a computer-based spreadsheet to track and record the results.

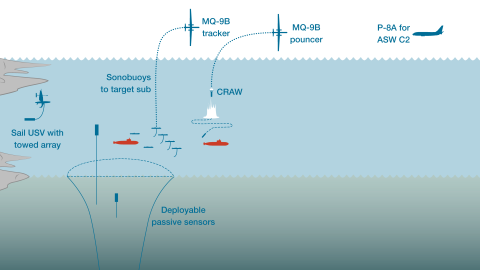

Tactical vignettes. Each team engaged Red during tactical vignettes, shown in figure 2.4, to inform which capabilities were beneficial or identify gaps that required new or different capabilities. Due to time constraints, Blue teams played only two or three vignettes of the nine total vignettes per turn, although they allocated forces to all the potential vignette operating areas. Vignettes addressed a range of missions appropriate to the setting, such as counterinvasion and air defense in the Cocos Islands or ASW in the Bali Sea. Hudson Institute used a computer-based adjudication tool to determine the outcomes of engagements during vignettes.

Figure 2.4. Blue Team Tasks During the TTXs

Source: Authors.

Blue teams built plans for tactical engagements that identified each element required to compose the associated effects chains, from finding targets to assessing results. To ensure realistic plans, the computer adjudication tool constrained teams’ selected kill chains based on the physical characteristics and performance of the systems.

The TTX scenario assumed that commercial and military space-based sensors provided situational awareness but that Australia continued to lack space-based targeting, and US targeting was not in position to support engagements around Australia due to other tasking. Therefore, the TTX mechanics and adjudication tool required teams to establish a tactical targeting source for each engagement. To capture the sensor, processing, and communications constraints of tactical targeting platforms like uncrewed surface vessels (USVs) or medium-altitude, long-endurance uncrewed air systems (MALE UASs), the adjudication tool limited the number of targets each sensor could maintain in custody.

The computer adjudication tool also automatically operated protective capabilities, such as air defenses and EW systems or decoys, that would respond to Red attacks. The computer tool adjudicated interactions of kinetic and non-kinetic effects stochastically rather than using a physics-based model, but it used parameters that were informed by detailed physical modeling where available.

Limitations and Areas for Further Study

This study does not reflect a comprehensive assessment of all the factors that could and should affect the ADF force design, such as alternative scenarios, logistics and communications constraints, and variations in Red force design. These factors, detailed below, should be addressed in subsequent analyses.

Scenarios

The proposed 2035 force design is based largely on a conflict in which US and Japanese forces are not available and the Red force is constrained as shown in Table 2.3. Other scenarios may result in a different or larger Red force or could allow the US military to devote more capacity to defending Australia. The ADoD could further refine the 2035 force design by assessing it against a wider variety of potential scenarios. This would enable it to establish a range of capacity necessary in each platform type and help identify which platforms or systems are useful across multiple situations.

Logistics

The TTXs conducted for this study did not address in detail the long-term sustainment of the force. The TTX mechanics and adjudication tool considered requirements to refuel ships and aircraft, but not repairs or maintenance. The game design also did not stress the logistics necessary to operate and maintain UxS deployed in expeditionary environments or at sea for extended periods. Because their endurance is generally lower than crewed platforms, uncrewed systems will demand more frequent refueling and maintenance than crewed platforms, even if they are operating close to Australia. The ADoD could address these considerations through detailed analysis of a more protracted scenario.

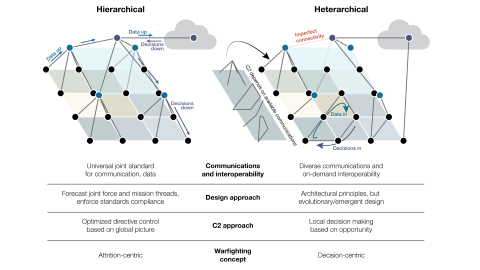

Communications

The 2035 TTXs did not address in detail the communication architectures and bandwidth necessary to enable effective intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and targeting (ISR&T) or command and control (C2). They also did not model the impact of communications jamming, which could increase the need for redundant networks or communication relays. Further studies could assess the operational concepts in the 2035 TTX using communication models that analyze the bandwidth and latency necessary for each kill chain and could incorporate the impacts of EW. This analysis would highlight where new capabilities or additional communication capacity may be necessary to improve throughput or resilience.

Laydown

The study did not address the infrastructure necessary to support the future fleet or ideal basing locations for its elements. The study team made this choice because Australia has a large number of existing bases and facilities that can host military units, and the ADoD can relocate units to address the changing strategic environment. However, the study’s recommended rebalancing of the force toward uncrewed systems would introduce requirements for facilities that can store and maintain large numbers of uncrewed vehicles.

Further research could address the changing infrastructure needs of the ADF as it evolves the force away from larger crewed platforms. For example, the ADF could reduce the number of active air bases it needs, allowing those facilities to become dual-use civilian and military airfields or transitioning them to host uncrewed aircraft.

Red Force Design

The 2035 TTXs did not consider a variety of Red force designs that could emerge during the next 10–20 years. Based on lessons from the war in Ukraine, adversaries could rebalance their forces toward uncrewed systems to address demographic challenges or to exploit autonomous capabilities that remove the uncertainty of relying on junior commanders to execute plans. Although a more uncrewed Red force would likely be more numerous and challenging from a capacity perspective, it could also have vulnerabilities that the ADF could exploit in its own force design. For example, autonomous systems relying on AI-enabled perception algorithms may be more susceptible to counter-C5ISR (command, control, communications, computers, cyber, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) capabilities than a system with an operator in the loop.

Further studies could test the proposed 2035 force design against a variety of Red force designs. For example, a replay of the 2035 TTX could place a common Blue team against three Red force designs, each with different mixes of crewed and uncrewed systems and different levels of vehicle autonomy. The TTX could reveal elements of the 2035 ADF force design that should change depending on the adversary’s evolution, as well as which ADF elements are robust across a range of potential opposing forces.

3. Campaigning and Fighting

To deter aggression, the ADF needs the ability to conduct wartime operations that increase an opponent’s risk of protraction and military losses. However, because the ADF cannot completely deny most forms of attack, the ADoD and Australian government need to conduct operations in peacetime to assess the risk tolerance of adversary leaders. The TTXs and workshops conducted for this study found that a single ADF force design could perform both of these major strategic tasks.

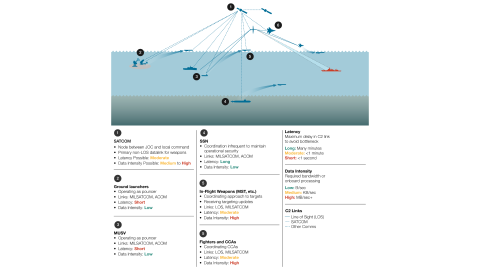

Because of Australia’s vast geography and small military, the ADF will also need highly distributed capabilities that can respond to and hold threats at bay until a concentration of forces can arrive. This suggests a basic construct like that shown in figure 3.1, with uncrewed pickets that detect and respond to threats; a mix of crewed and uncrewed pouncers that delay or stop threats; and crewed protectors that can surge to augment pouncers or defend high-priority locations such as cities or military installations.

Figure 3.1. Force Design Construct Developed in TTXs and Workshops

Source: Authors.

The construct shown in figure 3.1 would also support an ADF campaign to probe and assess adversary leaders’ risk tolerance and preferred attack scenarios. And because the individual units involved would be mostly small or uncrewed pickets and pouncers, the consequences of losses suffered in these probing activities would be reduced.

As described in chapter 1, the ADF force design should enable flexibility in posture, tactics, and force composition to pose novel and unexpected challenges against an enemy’s various avenues of attack. The reaction to ADF operations may yield insights about which attack plans adversaries prefer and which ADF concepts are most concerning to potential aggressors. By expanding the ADF’s reliance on modular uncrewed systems, the force design of figure 3.1 provides the capacity and recomposability to support a changing and diverse array of dispositions and operational approaches in a deterrence campaign.

Hedge Forces

Another feature of the posture model of table 3.1 is that it enables uncrewed systems to reduce the risk associated with high-consequence but low-probability scenarios facing Australia. Picket and pouncer forces are essentially hedge forces that provide the scale and persistence necessary for situations that are beyond the capacity of the crewed ADF and that would demand a substantial force restructuring to otherwise address.52 For example, the ADF would need a dozen FFGs or DDGs and nearly 100 fighters to counter an air campaign against the northern approaches when taking operational availability into account. This would tie up the entire surface combatant and fighter fleets, leaving Australia vulnerable to other threats.

Figure 3.2 Hedge Forces for the ADF

Source: Authors.

Using uncrewed systems in hedge forces allows crewed ships, aircraft, and troop formations to provide C2, prepare for higher-probability scenarios like border protection or interference with shipping, and back up hedge forces as part of the protector force. Because they address challenging threats that will rarely materialize, the ADF would benefit most from using hedge forces for ASW, offensive counter-air (OCA), and chokepoint and island defense operations, as shown in figure 3.2. These hedge forces would free crewed ADF units to focus on more common day-to-day missions and would enable a more dynamic defensive posture to undermine adversary planning as part of a deterrence campaign.

This chapter starts by describing concepts developed in the study that underpin the basic force design construct shown in figure 3.1 and the hedge forces of figure 3.2. The chapter then analyzes implications of these concepts for command, control, and communications (C3) and uncrewed system portfolios. Chapter 4 describes how the proposed ADF posture and operational concepts translate into a force design that fits within the ADoD’s fiscal and personnel constraints.

Operational Concepts

One of the main research questions for the study was how the ADF would operate and fight in the 2035–40 time frame. However, the ADF cannot wait more than a decade to implement new concepts like these. It will need to begin fielding them in the next several years to begin a deterrence campaign against PLA aggression. The following sections detail operational concepts developed by Hudson Institute for ISR&T, C3, IAMD, OCA, ASW, and strike/surface warfare missions.

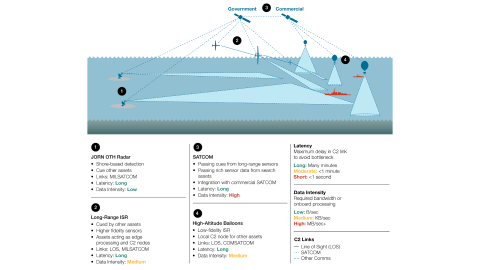

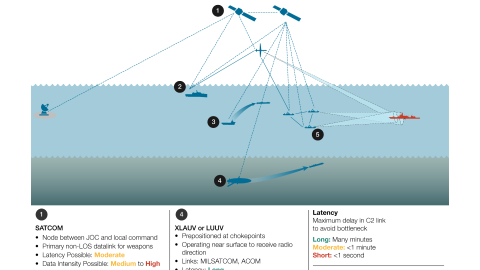

Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance, and Targeting

Military planning and operations start with ISR. In 2035–40, the ADF will be able to employ the wide variety of sensing approaches summarized in figure 3.3. Perhaps the most important new source of ISR is commercial space sensing, which has dramatically improved all militaries’ ability to maintain situational awareness of their region and provide warning of possible attacks. Countries close to a potential aggressor, like Ukraine, cannot exploit commercial satellite capabilities for warning because their attackers can quickly launch a large-scale assault. However, for the ADF, the relatively long distances from potential aggressors would enable commercial space sensing to provide adequate warning of enemy forces’ arrival.

A constraint on the ADF’s ability to exploit commercial space sensing is reduced coverage at lower latitudes. Most commercial low-earth orbit constellations are optimized to provide the densest coverage and shortest revisit rates in the mid-latitudes. This will support ISR over the northern approaches but will result in higher latency and lower accuracy along Australia’s southern approaches.53

Figure 3.3. Wide-Area ISR Concepts

Source: Authors.

The United States and other allied nations field pole-orbiting satellites to improve coverage at higher and lower latitudes, but these constellations do overfly Australia. For its part, the Australian government does not operate surveillance satellites, although it is pursuing a low-earth orbit constellation as part of a consortium to provide communications and space domain awareness.54 The US Space Force is addressing limitations of US military satellite coverage through initiatives like the Tactical Surveillance, Reconnaissance, and Tracking Program, which combines military and commercial space capabilities to provide surveillance data to allies and partners.55 This program could provide ISR data for ADF operations.

Australian forces can augment space-based ISR with the Jindalee Operational Radar Network (JORN), a set of high-frequency (HF) over-the-horizon radars (OTHRs) positioned across the northern half of Australia. Australia is the world leader in OTHR technology, and the ADF has refined its sensing concepts during three decades of JORN operation to detect ships and larger aircraft more than 1,000 nm away.66

Between commercial and military space capabilities and JORN, the ADF has sufficient ISR capabilities to build a regional operational picture. The ADF’s challenge, however, is translating that picture into the target-quality information it needs to launch long-range weapon attacks. Commercial satellites and JORN generally do not provide the precision or fidelity necessary to place a long-range weapon in the right location to see the target when its seeker turns on. And even if they do, the ADF cannot provide in-flight updates from commercial space services or JORN to weapons that could be in flight for hours before reaching their targets.

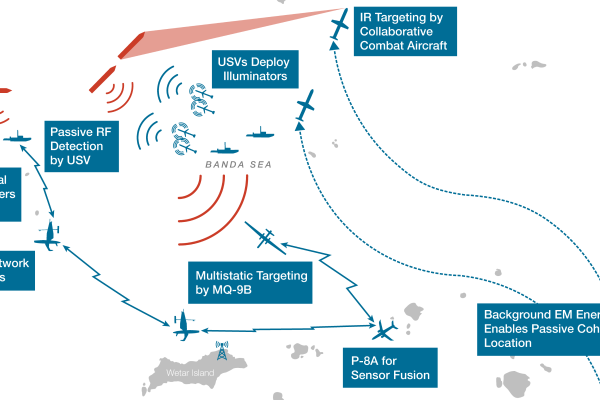

Figure 3.4. Proposed Passive and Multistatic Targeting Concepts

Source: Authors.

ADF forces will generally need a separate, local sensor to track targets and provide in-flight updates to weapons. Australia is far from most aggressors and will not experience the intense, large-scale missile fires that Ukraine endures. However, active monostatic radars would easily reveal an ADF unit’s location and identity, and anti-ship and anti-air missiles with ranges of more than 1,000 nm could strike a targeting sensor as soon as it emits.57 To manage counter-detection risks, ADF ISR&T concepts should limit radar use to crewed air-defense platforms such as guided missile destroyers (DDGs) and AEW&C aircraft that operate far from enemy forces as part of the posture construct shown in figure 3.1.

With radar too risky to use in most situations, ADF forces would turn to passive and multistatic sensors for targeting, as shown in figure 3.4. These approaches take advantage of the ADF’s need to field more uncrewed systems as part of a distributed defense and deterrence campaign. Passive sensors like radiofrequency receivers and electro-optical/infrared (EO/IR) sensors have inherently shorter ranges than radar since the target can reduce its signature through emissions control, camouflage, or jamming and obscuration. Moreover, passive techniques require multiple sensors to geolocate the target through triangulation because these sensors generally cannot obtain range information. Expendable or attritable uncrewed systems can overcome these disadvantages by approaching targets more closely and deploying at the scale necessary to geolocate contacts.

Integrated Air and Missile Defense

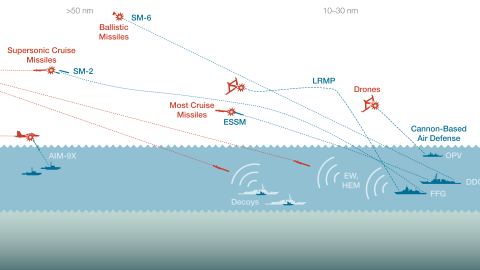

One advantage of the new posture construct in figure 3.1 is that it shifts most forward operations to uncrewed systems that require minimal or no protection from air threats. As a result, crewed pouncer units or protector forces stationed around Australia and its outlying islands would conduct nearly all ADF IAMD operations.

In its IAMD concepts, the ADF should apply recent lessons that US and allied militaries have learned in real-world air-defense operations. For example, US naval forces in the Red Sea have been preferentially using short-range air defense systems, such as guns or Evolved Sea Sparrow Missiles (ESSMs), that cost less and that they can carry in greater numbers than long-range surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) like the SM-3 or SM-6.58 The US Navy is also beginning to use EW more frequently to defeat drone and missile threats by confusing their seekers or jamming their satellite navigation signals.59

In ground combat, Ukrainian forces are employing similar approaches that rely on high-capacity, lower-cost defenses like short-range surface-to-air missiles (SAMs), guns, or EW and reserving sophisticated, long-range SAMs like the Patriot and PAC-3 to counter Russian hypersonic and ballistic missiles.60 As part of this approach, Ukraine is fielding a range of ad hoc air-defense systems that repurpose infrared-guided short-range air-to-air missiles (AAMs) to defeat missiles or larger drones.61 Reportedly, these systems have also been deployed on expendable USVs to provide an offensive anti-air capability in otherwise denied areas.62

Figure 3.5. Metinvest Radar Decoy Under Construction in Ukraine

Source: Metinvest.

Recent US and Ukrainian operations also highlight the growing diversity of counter-UAS concepts and capabilities. In addition to radar-guided cannon-based air defenses (CBADs), US and allied ground troops are using drones like the Coyote to down adversary UASs and using EW to jam drone control signals and sensors. New systems that can engage UASs at longer ranges or greater scale are now joining these capabilities. For example, existing 5-inch guns can launch General Atomics’ Long-Range Maneuvering Projectile (LRMP), which forces could employ against drones at longer ranges than traditional artillery rounds.63 And high-energy microwave (HEM) systems like the Epirus Leonidas can defeat drone swarms and some cruise missiles at dozens of kilometers by damaging or resetting their onboard electronics.64

Decoys, which fell out of favor in the years following the Cold War, have also proven themselves in Ukrainian and US air-defense operations.65 Ukrainian ground system decoys like the simulated radar shown under construction in figure 3.5 can often emulate the visual, RF, and infrared signature of the real system. Because an inexpensive, expendable system will be too small to simulate a modern warship’s visual signature, maritime decoys would rely primarily on radiofrequency and infrared signals to seduce incoming weapons away from protected platforms. For example, the US Navy Airborne Offboard EW (AOEW) decoy system in testing today is designed to draw incoming weapons away from a defended ship by emulating the radar return a missile would expect from the defended ship. A small USV, like the Saronic Spyglass shown in figure 3.6, could carry and power the AOEW payload to create a persistent air-defense decoy.66

Persistent ADF ground and maritime decoys will likely lack the fidelity to deceive adversary sensing and sensemaking capabilities for more than a few hours. However, these decoys would be more effective against cruise and ballistic missiles, whose seekers are less sophisticated than ship, space, or aircraft sensors. And because of the reduced space and airborne communication coverage around Australia, enemy missiles may not be able to quickly compare seeker data with data from space or airborne sensors. As a result, decoys could draw incoming weapons away from defended forces and reduce the number of weapons that real ships, aircraft, and ground units need to engage with air-defense systems.

Figure 3.6. US Navy AOEW Decoy (left) and Saronic Spyglass USV (right)

Source: Lockheed Martin.

Guns, EW, short-range SAMs, HEM systems, and decoys offer high air-defense capacity at low cost. But they have a significant downside: They require commanders to let threats more closely approach defended forces. However, with advancements in predictive AI-enabled models, IAMD C2 systems can help commanders determine which threats to engage at long range, which to engage at short range, and which to ignore because they will miss defended targets.67 IAMD battle management systems can also help operators identify which air-defense systems are best suited to counter which incoming threats.

The ADF is pursuing improved IAMD C2 capabilities through its Air6500 program, which seeks to provide broad-area airspace awareness and battle management for air defense of the northern approaches.68 These decision-support capabilities will be valuable in defending Australia, which has large areas that may not require protection and has a small force that must use its air-defense systems efficiently.

Figure 3.7 summarizes the IAMD concept for ADF units to protect themselves and nearby areas. This approach would shift most air-defense operations to shorter-range systems and increase the ADF’s reliance on non-kinetic capabilities such as decoys, HEM systems, and EW jammers. The concept also relies more on uncrewed systems to draw weapons away from defended forces.

Figure 3.7. Proposed New Air-Defense Concept for Deployed ADF Forces

Source: Authors.

Although it represents a naval application, the principles and capabilities shown in figure 3.6 are equally relevant to ground operations. The ADoD is fielding two National Surface-to-Air Missile System (NASAMS) ground-based air defense (GBAD) batteries, which will provide the ADF with six firing units of three launchers each. NASAMs can conduct short-range GBAD (SRGBAD) using AIM-9X Sidewinder missiles or medium-range GBAD (MRGBAD) using AIM-120 missiles.69 However, the ADF will need to add more firing units, complemented by new HEM systems and cannon-based defenses, to protect deployed forces across the northern approaches and support the OCA concepts described later in this chapter.

Another insight from the war in Ukraine is the growing prevalence of ballistic and hypersonic weapons. Through the Air6502 program, the ADoD is pursuing a dedicated MRGBAD solution that could include a system like Patriot and can defeat ballistic and hypersonic threats, but it is not funded in the 2024 IIP.70 The RAN’s three Hobart-class DDGs could conduct hypersonic and ballistic missile defense (BMD) using their Aegis Weapon System and SM-3, SM-6, or PAC-3 interceptors. The Hunter-class guided missile frigates (FFGs) may also incorporate this capability. This is, in part, why the force design includes these crewed warships in the protector forces stationed around Australia. From these operating areas, DDGs and FFGs can help defend units that the ADF has deployed on bases in northern Australia and intercept attacks against population centers, including Brisbane, Perth, and Sydney.

A potential weakness of this IAMD approach is that it consigns multimission warships to small operating areas close to the coast, where they may not be able to contribute to ASW or strike and surface warfare. To keep these protector platforms close to home, the proposed force design shifts most of their missions outside of air defense to UxS, as described in the sections below.

Offensive Counter-Air Operations

New IAMD concepts will improve the ADF’s ability to protect itself and civilian targets from missile attack, but the ADF will lack the capacity to sustain a purely defensive effort past the first few salvos. To present adversary leaders with a risk of unacceptable losses and delay, the ADF will need the ability to engage the sources of air and missile attacks—to shoot the “archers” before they can release their “arrows.”

ADF units conducting OCA operations can attack enemy aircraft either on the ground or in the air. Enemy fighters and fighter-bombers will be unable to reliably reach Australia due to long distances and a lack of aerial refueling. As a result, the main air threats to Australia are long-range bombers or theater and intercontinental ballistic missiles.

Bombers could launch missions against Australia from bases beyond the reach of ADF strike-fighters. However, the ADF could attack enemy aircraft on the ground using hypersonic missiles like the US Army’s Dark Eagle. The RAN could also use its future Virginia-class SSNs to launch missile attacks on bases to destroy enemy aircraft and their support infrastructure.

The ADF’s other approach to OCA will be to attack bombers in the air before they can launch their cruise missiles. Air-launched cruise missiles generally have ranges of more than 1,000 nm, allowing bombers to launch attacks outside the reach of ADF strike-fighters, which have combat radii of about 600 nm.71 ADF fighters could go farther using aerial refueling, but the RAAF can likely operate only five of its seven KC-30 tankers at a time and will need to devote them primarily to keeping combat air patrols and AEW&C aircraft in the air. ADF fighters will therefore need a different approach to engage enemy bombers before they reach their launch points.

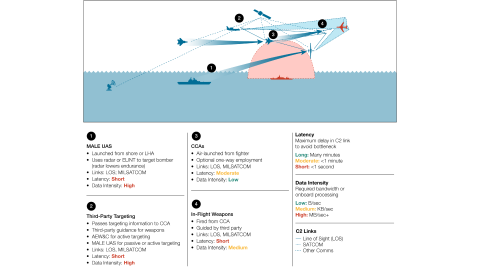

Figure 3.8. Proposed ADF OCA Hedge Force Concept

Source: Authors.

Figure 3.8 describes the OCA hedge force concept developed during the TTXs conducted for this study. In it, ADF fighters remain on alert on northern bases such as Darwin and Tindal or fly continuous combat air patrols if an attack is likely. The fighters, equipped with smaller collaborative combat aircraft (CCAs) like the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Longshot, launch when long-range sensors like JORN detect bombers. Larger CCAs, like the MQ-28 Ghost Bat, can accompany them.72 Fighters would launch their on-board CCAs when they approach their maximum range, which aerial refueling from KC-30s can extend; these refuelers would already be supporting E-7 Wedgetail AEW&C aircraft orbiting in the northern approaches. The E-7s or—if the range is too far for the E-7 to reach within RAAF tanker capacity—short take-off and landing MQ-9B UASs launched from amphibious assault ships (LHAs) guide CCAs into the vicinity of incoming bombers. The CCAs would attack bombers with AAMs like the AIM-120D medium-range missile or AIM-9X short-range missile.73

The kill chain shown in figure 3.8 demands a substantial portion of RAAF force structure. For example, an AEW&C orbit requires two or three aircraft total, each fighter combat air patrol requires three or four, and the fighters need about eight CCAs per orbit. The RAAF KC-30 fleet would also be fully occupied with keeping the force airborne. The ADF will lack the capacity to establish this kill chain in each possible bomber attack lane across Australia’s northern approaches, which could demand a dozen or so force packages like that shown in figure 3.7.