Following is the full transcript of the April 30th, 2020 Hudson online livestream event titled The Future of Venezuela: A Conversation with Special Representative Elliott Abrams

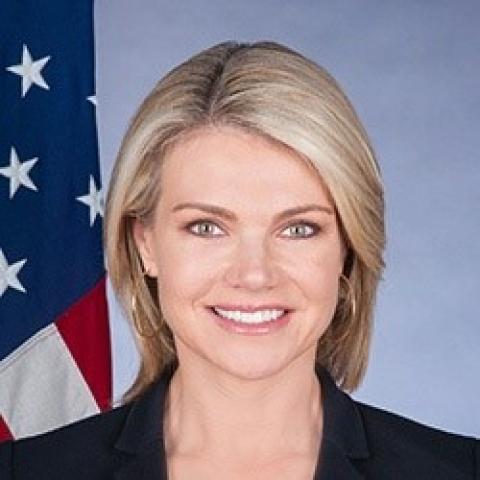

Heather Nauert: Good morning, and welcome to the Hudson Institute. I'm Heather Nauert, a senior fellow here at Hudson. Today, we're joined by the US Special Representative for Venezuela, Elliott Abrams. He has served three US Presidents and has taken the diplomatic lead on trying to fix the situation and restore true democracy to Venezuela. He joins us now to talk about a new plan that was recently put forward by the State Department.

It's called the Democratic Transition Framework. And, sir, thank you so much for joining us. We have a lot of other things to talk about today, including the oil markets, the impact that prices have right now on Venezuela narco-terrorism, and a lot of other issues, including coronavirus and its impact on Venezuela. But let's start first with the new diplomatic outline that you have laid out. And tell us a little bit about it and what it includes.

Elliott Abrams: Thanks, Heather. I'm really glad to be with you today. It's a framework for how we get from where we are, we’ll just say a “dictatorship” in Venezuela, back to the kind of democracy they used to have. And we put it forward because everyone has been asking the question, "Well, how does this happen? How do you get there? And what does it take to lift US sanctions?" So, in this framework, we outline, and I should say outline, this is a proposal by the United States.

Some people have said it's an outrage because it's an ultimatum. It's not an ultimatum. It's a proposal. And what it suggests is that they need a transitional government that would run the country for let's say nine to 12 months and hold three presidential elections. And that would be an agreed government, a negotiated transitional government, in which all the parties would be represented. They would choose an interim president.

The National Assembly would stay as it is with Juan Guaidó as its president. They would hold those elections in it for the first time in a long time. They'd have a democratically-elected legitimate president. When the transition started, we would suspend US sanctions. When the transition was completed, that is, they hold really free presidential elections. Then, we would permanently lift the US sanctions.

Heather Nauert: What reaction are you getting from the international community so far?

Elliott Abrams: It's really been pretty good. We've had a large group of Latin American countries and the EU countries thank us for doing this. Some of them saying just, "We're in. This is a great idea." Others saying, "We think this is the thing that needs to be taken into account, that needs to be worked on, because this is the path forward." Guaidó himself, Juan Guaidó whom we recognize as the legitimate interim president of Venezuela has what he calls a national emergency government, which is really the same proposal.

There's been a tremendous amount of international support of countries that want to help, that is, rolling it back to democracy saying, "This is the transition that they need to go through."

Heather Nauert: Just the other day at the United Nations, there was a closed-door session of the Security Council in which coronavirus was the topic of conversation for Venezuela and the impact there. But one of the things that came up of course is Russia and China. And Russia and China have continued to meddle in the affairs of Venezuela. So, what do you see it taking to eventually get Russia, China, and there's also Iranian influence there, to remove those outside actors from the future of Venezuela?

Elliott Abrams: Yeah. I would say the four countries that are the most significant bad actors, Russia, China, Iran and Cuba.

Heather Nauert: Oh, right, Cuba, of course.

Elliott Abrams: Yeah. So, each one is different. The Cubans desperately need Venezuelan oil. And the Cubans, by supplying roughly 2,500 intelligence agents who are all over just permeating the military, even the presidential palace, Maduro's own bodyguards are not Venezuelan. They're Cuban. That's one relationship. China at this point is mostly a commercial relationship. They have lent Venezuela something on the order of $15 billion and they want it back.

And what we keep saying to them of course is, "Well, you're not going to get it back from Maduro who is bankrupting the country." The Russians are yet in another situation. First of all, they are the main protector of the regime internationally, particularly in the Security Council of the United Nations. Secondly, there are a couple of hundred Russian military people on the ground helping them train and recondition their Sukhoi jets, their tanks.

All of the military paraphernalia they bought from Russia over the last 20 years, a lot of weaponry. So, Iran now, the last one, the numbers are not great, but it's been interesting. We've recently seen Secretary Pompeo mention this yesterday in a press event he did. Thursday morning, he said, "We see Iran now sending more and more planes to Venezuela, particularly this week.” And we think, our guess, is that they're being paid in gold.

And that those planes are coming in from Iran that are bringing things for the oil industry are returning with the payment for those things, gold. One of the reasons I mentioned that is not just to show that Iran is playing an increasing role, but notice that it's cash. And so, neither Russia nor China is willing to give their great friend Maduro a dime. Everybody wants cash on their hand. And we know that Maduro has, over the last year, wanted Russian and Chinese additional loans, additional investments, and he has not gotten a dime.

Heather Nauert: There's a lot to dive into there. And one of the things you mentioned of course is Iran. My understanding, and perhaps you can confirm this, there's a new oil minister in Venezuela. And that person has some close ties, according to my understanding, to Hezbollah and also to Iran. Can you confirm that?

Elliott Abrams: Yes. This is Tareck El Aissami, who is sanctioned by the US, indicted by the US for involvement in drug trafficking. And he was, just this past week, named the new oil minister. So, this is a regime that is dealing with some of the worst states and entities in the world. And it isn't surprising that a regime like Maduro's would reach out for help, where to run. Because countries that are not involved in that illegal conduct, smuggling of weapons and other things, support for terrorism. Most don't want to have anything to do with Venezuela.

Heather Nauert: So, these nations have a pretty strong toehold in the Western Hemisphere now. And I know we want to talk about democracy in Venezuela, but I'm just wondering, what is it going to take to remove those countries from this important country in our hemisphere, to get them out, Russia, China, Venezuela and Cuba as well?

Elliott Abrams: Well, that's a question we ask ourselves all the time. Because obviously, Maduro is still there as you and I speak. The hold that his regime has is quite fierce and brutal. You might ask, "Well, why haven't people in the army, nationalistic or patriotic people in the army, done anything about this?" And the answer is, I think to that one, the Cubans. What are they doing there? What they're really doing is they're spying. They're spying on everyone in the military.

They're deeply in the intelligence agencies. And their whole goal is to protect Maduro and prevent coups so that they keep that flow of oil going. "What happens if you protest? Why don't people protest more?" I have heard that question. "Why aren't the Venezuelans protesting more?"

The jails are full of people who were protesting. Moreover, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in a report that she did last year, said that the Police Special Forces in Spanish, the initials are FAES, F-A-E-S, had killed 7,000 people, 7,000. So, I think we can understand that the brutality of this regime is really what has kept it in place. But something is changing now. They've never been under this pressure before.

Oil prices, I mean, it's a one growth economy, oil. And oil prices obviously have collapsed. We've increased their sanctions. So, there's really no market for Venezuelan oil. And Maduro himself has admitted that the sales price they're getting is lower than the cost of production. So, they're getting no income there. Add to that, secondly, the pandemic.

Heather Nauert: Other countries that have bought their oil in the past can get it more cheaply from countries that are a lot closer to them than they can get it from Venezuela. So, that revenue stream may increasingly dry up for Venezuela as well.

Elliott Abrams: That is exactly right. I mean, why buy from Venezuela if you can get the same product from say the Arabian Gulf? And we do think their markets are drying up and their income is drying up. The condition of the Venezuelan people is a terrible thing to behold in what was a few decades ago the richest country in Latin America. But these pressures are combining and they're getting worse. So, what the Secretary said yesterday was, "His days are numbered."

We really think that's true. And the Secretary announced yesterday that he instructed us in the department to start doing again something we were doing about a year ago, which is planning for the reopening of US Embassy. We can't do it. We won't do it with Maduro there because it wouldn't be safe. But we think a transition is coming and we need to be prepared for it.

Heather Nauert: Okay. So, a couple of things that have changed and evolved since you took on this position, just over a year ago, the United States policy has largely been on putting sanctions in place against Maduro and his cronies. We haven't seen him leave as a result of that just yet. The United States has provided money via USAID and others to Juan Guaidó, and Guaidó’s team, in order to keep them afloat and to encourage democratic reform.

But that has still failed to achieve the results of getting Maduro out. So, you've put forward this new plan and you started to outline it there, but I'd like to dig down into the details of the democratic transition framework. And talk about the Council of State that you propose setting up and which parties would feed into that democratic Council of State, and how that would lead to a transitional government.

Elliott Abrams: Thanks for the question. We thought, look, this has to be a plan that would appeal to many, many millions of Venezuelans. Now, something like a fourth of Venezuelans still consider themselves Chavistas. That is, they may not like Maduro and they can see he is destroying the country, but they were followers of the late Hugo Chavez. And they still support his party, even though they don't support Maduro. And there's also the military.

Obviously, they have a role to play here. They could prevent change. And they do have a role actually in the future. I mean, look at Venezuela, a country with long borders, and particularly Brazil and Colombia with a maritime border. You've got Colombian narco-traffickers and Colombian terrorists who are in Venezuela, the FARC, ELN. You've got criminal gangs, many of them armed by Maduro and his government. So, you're going to need security forces.

So, what we built in here was, how did this happen? What's the structure? The structure is that in the National Assembly, there are basically two sides, the Chavista Party, and Guaidó is the leader of the opposition, of the Democratic Party. Each side would pick two individuals, and each could veto the other. And we did the veto because we wanted, not each side to pick its most radical guys, but to pick the men and women that are generally viewed as reasonable, sensible people.

Those four people would form the Council of State. That would really be the executive branch. And those four people would pick a fifth, who again would have to be a compromise candidate to be the interim president. And what we're saying to people in the military, and in the Chavista Party is, "Look at this structure. This is done to protect you, to be fair, to be balanced." So, that we're not saying, "Okay, you're out. You mishandled things. You go to jail."

We're saying, "Everyone should have a fair share, not a criminal in this transitional government to hold free elections. And by the way, this government is needed because you can't say Maduro is going to hold a presidential election. He held one in 2018, the corrupt one that got Venezuela into this political mess, because everybody in the world understood that was an unfair election." So, that's the basic structure.

We have also said by the way, "They're going to need a Truth and Reconciliation Commission like from South Africa to the formerly communist countries in Eastern Europe, most of these countries have had some historical lookback, a Truth Commission, a Reconciliation Commission in a form of amnesty." And also we've said, "We're willing to lift sanctions right at the start for people who we've sanctioned only because of the job they hold.”

That is, if you're the Minister of something, labor, well, we've sanctioned you because you're part of Maduro's government. If you leave that job, the sanctions come on off.

Heather Nauert: But no removal of sanctions for Maduro himself?

Elliott Abrams: Any sanctions for human rights violations for example, stay on. Maduro's case is tougher. He has been indicted. And we have made it very clear, the indictments do not come off. Sanctions are a matter of policy. State Department, Treasury Department decide on sanctions. The judicial system, and we had to explain this to a lot of foreigners in our country, is independent. And juries in New York and Florida indicted Maduro and others and they can try those cases if they want.

They can try dealing with the Department of Justice. We at the State Department, we can talk to people about sanctions. But it's very clear, we do not talk to people about indictments. Hire a lawyer to talk to DOJ.

Heather Nauert: The United States has no extradition treaty obviously with Venezuela. What do you see happening to Maduro in the long run? If the elections go forward and someone else is elected even though he can conceivably run if he wants to, or at least somebody from his party, where do you see him going?

Elliott Abrams: Yeah. He can run. I have colleagues who wish he would run because he'd be the weakest possible candidate for the Chavista Party. His support is now not far, almost 10%. So, he might stay in Venezuela. He might go to Cuba. Or also, obviously, we have no extradition treaty in Russia, Turkey. Those are two other countries that don't extradite people to the US. So, he would have a few choices. He needs to be extremely careful, however.

Because if he were to go to another country, he could be grabbed and extradited to the US, which is of course what has happened in a few other cases in the past.

Heather Nauert: Part of the plan calls for the election of an interim president, and that interim president wouldn't be able to run for the presidential election himself or herself. So, how do you see that playing out? And I'm also wondering if this overall strategy somehow diminishes the role of Juan Guaidó in any way that you see it?

Elliott Abrams: Again, very good questions. Why did we do that in our plan? Again, it's a proposal. It's not an ultimatum. But why did we say that? We thought, when you are the political crisis that Venezuela is, people are going to be very suspicious that the election will be free. If you are the interim president, again, the Council of State, four members elected by the National Assembly, two for each side. And those four agree on a fifth person, a man or woman, who would serve as the interim president.

That man or woman can't run. Because we thought in the Venezuelan system, you want somebody to say, "I'm not a candidate. I'm just going to try to run a free election and it won't affect my personal interest." If that person could also run, we think many, many millions of Venezuelans would say, "Oh, look. He or she is going to fix it so that they can be reelected." Juan Guaidó, I would just say, if Juan Guaidó were in this Council of State serving as president, he couldn't run under our plan.

And so, I don't even think he wanted because I think he may well want to run for president. But remember that during this period, he remains the president of the National Assembly. And the National Assembly is critical in the plan that we've proposed. The National Assembly elects the four members of the Council of State, and you elect a new Supreme Court membership, and you elect the members of the Electoral Council. That's actually going to administer the election.

So, the National Assembly, which is the only democratically-elected institution of Venezuela, is critical, and Guaidó remains its president.

Heather Nauert: When we talk about international negotiations or plans, we often talk about confidence building measures, and you hit on something a short while ago where you talked about how people are skeptical of free and fair elections, believing that that simply isn't possible in a country like Venezuela. So, what confidence building measures can you put in place to try to reassure people that things will be handled fairly this time?

Elliott Abrams: The beginning I think is just the departure of Maduro so that they know, "Well, this is not going to be what happened a year ago." I think the presence of a very, very large number of international observers from the beginning, not on election day, but from months in advance, we do that very well in this country. The National Democratic Institute, the International Republican Institute, Freedom House, the International Foundation for Electoral System, and other countries do too.

There's a lot of experience with this. And everybody now knows you've got to start early. You've got to make sure that there's no censorship, that everybody has equal access to the media. And they're going to have a hard time in Venezuela establishing a voting system because it's been a while since they had a free election. The last one was 2015. So, if you had an election the end of this year, it's five years since the last one.

In those five years, think about this, five million Venezuelans have left the country. Now, once Maduro goes, some will come back. But you probably need to arrange also for voting outside the country, in places like Bogota, Colombia, where there are thousands of Venezuelans. So, it's a hard test. But if you have an honest political council and lots of international help, including some money, we're confident it can be done.

Heather Nauert: And we've talked about the timeframe for transitional government has been six to 12 months. But this overall plan, very ambitious, including cleaning up its Supreme Court, letting out political prisoners, getting a free media back in place. It's a hugely ambitious plan. What's the overall timeline for that?

Elliott Abrams: Well, if you say a year for the election, which I think is reasonable, you've got this one year to begin to try to get the economy moving again. And I think there'd be a lot of help from the international community. Meaning, above all, the World Bank and the IMF. Because you start that, you start some migrants and refugees coming home. You start rebuilding a political system. The oil industry, a couple of years ago, looked a lot better than it does today, obviously.

And unless the world economy picks up, that's going to be quite difficult. But if you assume we're talking about let's say a year from now, we all hope the world economy has picked up a lot. And so, if you think about it, the main customer for Venezuelan oil for decades and decades, was us. You mentioned before the geography. Well, of course, it just went to the Gulf Coast where refineries were set to handle the quite thick, viscous high sulfur content Venezuelan oil.

Well, once Maduro goes, and we have repaired our relationship with Venezuela, that can restart. So, I think one has to say, honestly, it's taken 20 years for the Chavez and Maduro regimes and the socialist policies they have followed to destroy the Venezuelan economy. It's not going to come back in one year. It is going to be quite a long time before they achieve the levels of prosperity they had the day that Hugo Chavez took office.

Heather Nauert: I see you're describing something that requires a lot of patience. But it's taken this long for Venezuela to get to this really sad and disastrous point, because it's such a country that is rich in its culture and in its natural resources, and everybody. As you and I have seen in the State Department, people who are forced to leave their countries really only want to go home, which leads me to something else, and that is the issue of migration.

You touched on millions of people having left Venezuela. So many have crossed the border into Colombia. Yet, in Colombia now, they've been affected too by coronavirus, of course. A lot of those Venezuelans aren't able to get jobs, aren't able to pay the rent in Colombia. So, some of them now are going home. And I've seen reports that indicate in the tens of thousands maybe returning to Venezuela to a much more fragile state than the one that they left.

So, what do you see that situation looking like for them upon the return home? And what can the United States do to help?

Elliott Abrams: Well, it's a very difficult situation. We think roughly 50,000 have returned, which in a way isn't a big number in that we think there are about two million Venezuelans in Colombia. By the way, we should really know the way the Colombians have been so hospitable for years. There were many years when Colombians went to Venezuela because it was so rich and it was a democracy. And so, they are returning the favor.

And they were being really very hospitable and trying to take care of Venezuelans. We really don't know whether that 50,000 will turn into a few hundred thousand who've gone back or will those 50,000 go back to Colombia if coronavirus gets a lot worse in Venezuela, because Colombia has a better medical and hospital system? What are we trying to do? Well, we're trying to help.

First of all, the United States has given about now, I'd say, about $670 million to help Venezuelans inside the country and who are outside the country. Last, I guess it was about a week ago, we announced there'd be $9 million more that USAID is going to give exclusively for COVID-19. Juan Guaidó has access to some funds in the US that were left over from the Central Bank of Venezuela. And he is trying to get the regime to agree to let him give $20 million to UNICEF and other agencies.

They are afraid to accept the money because they're afraid of repercussions from the regime. But we will be continuing to give help. You mentioned the UN session that was held this week.

Heather Nauert: Yes.

Elliott Abrams: The Maduro regime sent a big long letter, these pages and pages, saying, "Our sanctions are killing people in Venezuela." Of course, US sanctions never, never cover humanitarian goods, medical good, food, never. They gave five instances of when they said our sanctions prevented people from giving medical goods, food to Venezuela. All five of them were actually incidents that took place before our sanctions went into effect. So, they were just following. We have said that publicly and privately to the regime.

Heather Nauert: If I could pause you there for one minute because that's one of the things that drives me crazy about so many in the media or some people, other foreign policy, they claim that sanctions hurt people in that way. And we’d come back time and time again and say, "There are exemptions for food. There are exemptions for medicine." And still, that falls on deaf ears, whether it's in Venezuela or Iran. I just wanted to mention that.

Elliott Abrams: You're absolutely right. And believe me, the regime knows that what you just said is true, because throughout last year, they were buying food in the United States. They know they can buy all the food they want in the United States. We have said to them, "Look, if there's anything you want to buy, pacemakers, you want to buy food. You want to buy any medical aid," and the company is reluctant because of sanctions or the bank doing the transaction.

So, they know there are sanctions. We say, “Tell us. Tell us.” We can ask the Treasury Department to give them a comfort letter or sometimes you just call the bank and say, "This is the Treasury Department. Don't worry, do it." Not once have they been able to give us a transaction where our sanctions actually blocked it. We're still waiting.

Heather Nauert: So, back to Russia and China, and also Iran and their influence in the region, I know we touched on it before, but I feel like we haven't drilled down enough on that. How does the United States, backed by the international community, backed by the people of Venezuela, who probably don't want those regimes influencing their country and meddling in their country, what can be done to try to get those countries and those regimes out so that Venezuela can finally be a free and prosperous country without the influence of others?

Elliott Abrams: The critical thing here is probably to get a democratic government that is acting in the interests of Venezuelans. Take the Cubans for example. What are they doing there? They don't bring any food. They don't bring foreign aid. What are they doing? Spying. So, I think the Venezuelan army would be very happy to be rid of them because they are, as I said before, infiltrating every aspect of the national government.

In the case of Russia, I mean, we all know what they're doing. This is an effort to get a foothold in the Western Hemisphere. They have Cuba, but this is on the mainland for the first time. They're not willing now to spend any money. It's quite interesting, actually. They did make loans. At one point, Rosneft, a fuel company, it was owed $5 or $6 billion. But the last few years, they're taking money out last year.

And think of the health problems. Think of the food shortages in Venezuela. Last year, Rosneft took a billion, $800 billion out of Venezuela back to Russia. They're also paying off military debt to Russia. You think the regime could if they cared enough about the Venezuelan people, could say, "We don't want to pay that back right now. Give us another few years to pay it back." But that didn't happen.

So, I think that the critical change here is not going to come because we're going to persuade Vladimir Putin that he should care more about the Venezuelan people or certainly about Venezuela democracy.

Heather Nauert: Right.

Elliott Abrams: It's going to come when they get an elected government. An elected government that like the rest of the governments in Latin America, may not have the same policies that we do on everything. They don't have the same economic policies, but it's going to be in the interests of their people. We don't have the same views of economics as the president of Mexico. Yet, we hear President Trump all the time saying how well they're working together on many, many issues.

Venezuela used to be a close friend of the United States. We want it to be again, and I am confident that the vast majority of Venezuelans want to be close friends again as well. It just cannot happen while the Maduro regime is in power.

Heather Nauert: I want to ask you a question because we talked about Rosneft, but about PDVSA (Petróleos de Venezuela). And there was a report that came out earlier this week, it was in Reuters, that PDVSA wants to essentially invite investors back in, which is ironic, because the company once had lots of Western and other investors, and then kicked them out. And now, they want them back. Can you confirm that report and what can you tell us? What's your take on that? What do you think will happen?

Elliott Abrams: I've seen the report and it's been in the press in Venezuela. Whether it'll happen or not is a different question. I think they have a big problem. Why are they doing this? When the money was rolling in because the oil was selling for $50, $60, $80, $90 a barrel, they weren't doing this. They're doing this now because they feel it's the only way to get oil companies maybe to put some money in. I don't think it's going to work.

Because right now, why would you invest in the oil sector in Venezuela? I mean, it is very heavy crude, so it's expensive to refine. And many, many countries, starting with the United States, won't take that oil. There hasn't been any real investment in the sector for years or even decades. It's quite decrepit. And then, there were US sanctions. So, who are the companies that are going to do this, European companies? I don't think so, not with our sanctions in place.

Heather Nauert: We talked about China before, and we know what China tries to take for collateral when loans aren't paid back. We talked about that a lot through the US's Indo-Pacific Strategy and how China will get countries into this debt trap situation. Do you think China is trying to grab any pieces of national infrastructure in Venezuela? They're not going to just give up their money and go home with empty pockets, I wouldn't think.

Elliott Abrams: No. And when we talked to them about Venezuela, which we do, what they generally say is, "We don't have a geopolitical interest here. That's not what we're doing. We want our money back." That's their message. I don't think they're going to put any more money in. I think that if Maduro thinks that with this announced plan for PDVSA, the oil company, they're going to get lots of Chinese investment.

I think the Chinese are frankly sick and tired of putting money and not getting repaid. And we've seen Chinese projects in Venezuela that just get stopped as soon as they stop getting their repayments. So, I don't think it's going to be China. Russia is conceivable because Putin's interest really is geopolitical, not financial.

Heather Nauert: Well, a lot to watch there, certainly. A lot of what we're talking about today depends on security. Elections will depend on people having confidence and security in their country. Western investment and investment from other countries and industries will depend on security. You mentioned, looking forward to the US Embassy reopening at some point. What do we need to get to those points?

And can you give us any timeline which we think something like that might be possible?

Elliott Abrams: That's a hard question. Security is a huge problem. Even if you assumed a very smooth political transition, you'll still got those Colombian narco-terrorists who've been given safe haven. They're not going to leave overnight. You've got criminal gangs that are doing narcotics trafficking. You've got the so called Colectivos, which are armed gangs armed by Maduro. How do you bring all those under control?

That's one of the reasons that we think we could, after Maduro goes, begin to revive a partnership with the Venezuelan military. Because the real answer to that ought to be, the military, their military, the army and the police, and that ought to be the answer. But you're right that international oil companies and others are not going to look just at the natural resources. They're going to look at the security situation. Same thing for us, reopening the embassy.

We left because the Maduro regime really wouldn't provide security for the embassy. Before we reopened it, we would need to be sure there's a government in place that guarantees the security of that embassy. We have marine guards and so forth. But fundamentally, you rely on the security guarantees of the government.

So, if you want to be an optimist, this could start happening. But it could start happening tomorrow if Maduro would leave. It isn't going to be the smoothest transition in the world. It's not like the Czechs or one of those experiences. I think we have to be honest about that. But I think that, really, once Maduro and the Cubans are gone, you'll find that the army really does want to serve as a patriotic national army and bring security to the country.

Heather Nauert: Well, part of that army and that military, I want to ask you, have emboldened Maduro, have allowed him and enabled him to stay in place. So, how do you see getting that military to back away from Mauro and come around for the benefit of the country's own people?

Elliott Abrams: Yeah. And there's a lot of corruption. There's no question. I mean, how has Maduro kept them in line? Two ways, one is terror, the Cubans. But the other is money, allowing them to make money corruptly, bringing them into corrupt schemes. There's no question about that. They're going to need to do their own house cleaning. It's not going to happen overnight. It may not happen during the transition.

Because you won't have an elected government with all of the confidence and credibility that it's going to have. I do think that the problem is mostly at the higher levels. Hugo Chavez at one point basically thought, "Well, how do I keep all these colonels loyal? I know. I make them all generals." And Venezuela had more, this is literally true, Venezuela had more generals than every NATO country, including the United States altogether.

So, there will need to be changes. There's no question about that. But we do think that as you go down in the ranks, you have more and more people who want to serve the country, who look at their own sisters, brothers, aunts and uncles, cousins, and see them suffering, and know that the country needs a radical change.

Heather Nauert: So, I always like to leave things with not only a little bit of optimism but also a prediction or a bit of a heads up on what we think might come next. If we can look ahead and try to make some news here, what can you share with us that might happen next?

Elliott Abrams: Well, I think the situation in the short run, meaning, the next couple of months, is going to get worse internally. I think the pressures are going to grow and grow. And as Secretary Pompeo said yesterday, really, Maduro's days are numbered. I think you'll see more and more pressure from outside the country and more importantly from inside, that he needs to go. And the transition really does need to begin, and it needs to begin in the next few months.

Heather Nauert: Let me ask you one last question about giving voice to the Venezuelan people and helping to better support any media or reporting that comes out of the region. What can the United States do a better job of, or NGOs that the United States works with, to try to give voice to some of those, not only the dissidents, but also people who report down there? What could we do better?

Elliott Abrams: Well, communications are critically important particularly in a country where there is censorship. Whatever we can do to support the remnants of the press, whatever we can do to support websites that provide independent news, whatever Voice of America and BBC, and Deutsche Welle, and all these other international stations can do, is critically important for getting the news into Venezuela, because people are not getting it from the regime.

Elliott Abrams: So, this question of communications is absolutely critical to bring change to Venezuela.

Heather Nauert: Right. Special representative to Venezuela, Elliott Abrams, sir, thank you so much for your service to our country, your continued service. You're a real public servant and a diplomat as well. We certainly appreciate it. And it's a real joy talking with you today. So, keep us posted on how the situation goes, and always happy to talk with you about that message.

Elliott Abrams: It's been my pleasure, Heather. Thanks very much for having me.

Heather Nauert: All right. Thanks again. We'll talk to you real soon.