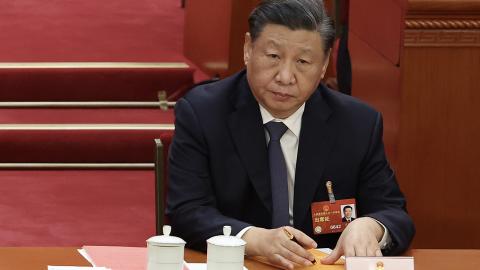

Xi Jinping spoke with unusual candor about the international situation at the start of China’s recent National People’s Congress. According to him, “Western countries — led by the U.S. — have implemented all-round containment, encirclement, and suppression against us,” and this campaign is “bringing unprecedentedly severe challenges to our country’s development.”

He forgot to mention that his own actions have caused this backlash. China’s belligerence is increasingly alarming its neighbors, who are drawing close to each other and to the U.S. for protection. To counter them, Xi is trying to centralize his control over China and make gains in Europe and the Middle East. The question is if China’s neighbors can build up defenses faster than China can break through them. And so far, the signs are not encouraging.

As the international situation grows more fraught, Xi is trying to fix China’s precarious finances and harden the country against further sanctions. To do so, he is doubling down on centralized control. At the congress, Xi announced that Communist Party leaders would take more direct control of China’s financial policy. Another party-directed commission will lead China’s high-tech sector.

He also showed off his new diplomatic clout and announced his worldwide ambitions. Celebrating the diplomatic thaw China recently brokered between Iran and Saudi Arabia, Xi said that Beijing should “actively participate in the reform and construction of the global governance system.” As he arrived in Moscow last week, Xi proclaimed that China is ready to “stand guard over the world order.”

Xi is not neglecting China’s near abroad, though. His government is exerting greater control over disputed territory in the South China Sea and now blocks foreign companies from laying underseas internet cables there. China is also continuing its long-running campaign to wear down Taiwan’s morale and diplomatically isolate the island, and it recently convinced Honduras to drop its diplomatic relations with the Taiwanese.

Of course, not all is going smoothly for Xi. The Biden administration has made some important moves of its own, such as reaching an agreement with the Philippines to allow more U.S. access to some of its military bases. These bases would be helpful in a crisis in the South China Sea or Taiwan, and President Marcos has said that “it’s very hard to imagine a scenario where the Philippines will not somehow get involved” if such a crisis arises. The Netherlands recently confirmed that it will cut off China from the only machines capable of producing cutting-edge computer chips, significantly harming China’s tech sector. And President Biden recently announced a plan to co-produce submarines with fellow AUKUS members Australia and Britain.

Perhaps most important of all, after years of acrimony, South Korea and Japan are resolving a dispute over claims stemming from Japan’s mistreatment of Koreans during World War II. South Korean president Yoon’s visit to Japan earlier this month didn’t just allow the two countries to resume security cooperation; it may also have marked the start of another big shift in regional politics.

A senior Korean official said that “although we have not yet joined the Quad” — the strategic security partnership between the U.S., Australia, Japan, and India — the Yoon administration “has been emphasizing its importance in terms of its Indo-Pacific strategy.” As part of a “gradual approach” to seeking Quad membership, South Korea “will have to proactively accelerate working group participation” with the group. Whether or not South Korea joins the Quad, closer interaction with the group will tighten the circle around China.

The question is which strategy will pay off faster. Xi’s control over China’s government is no guarantee of control over China’s future. As China’s recent agreement to bail out Sri Lanka reveals, Xi projects such as the Belt and Road Initiative can create financial risks for China. But even flawed successes can still serve his purposes: Though Iran and Saudi Arabia are unlikely to have a warm relationship, Xi doesn’t really need them to. Egypt and Israel did not become fast friends in the 1970s, but the United States nevertheless managed to drive them both away from the Soviets by demonstrating that only Washington could deliver on their demands.

Meanwhile, there are still causes for concern among America’s partners and allies. As the pro-AUKUS analyst Zack Cooper warns, if the submarine deal works as planned, “the United States could essential lose nearly one-tenth of its submarine fleet in the decade of its greatest need.” Moreover, Japan and South Korea have repeatedly tried and failed to resolve wartime issues since the first attempt at a final settlement in 1965, and 59 percent of South Koreans oppose Yoon’s rapprochement.

The ground is shifting rapidly in Asia, and the swift-footed and clear-eyed have much to gain. Biden is betting that slow and steady will win the race, but, in this situation, he risks doing too little too late.