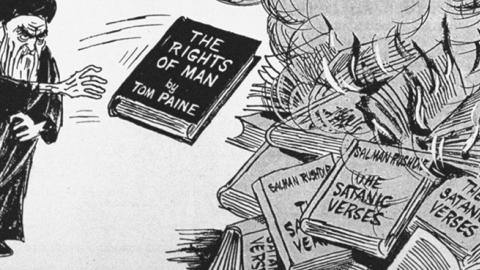

The initial theme of Mustafa Akyol’s "Liberty Forum essay":https://www.lawliberty.org/liberty-forum/islam-blasphemy-and-the-east-w… is the famous or infamous fatwa that the Ayatollah Khomeini pronounced in 1989 against the novelist Salman Rushdie, author of The Satanic Verses. Khomeini condemned Rushdie, as well as all of his collaborators, to death for this book’s alleged insult to Islam. Although we have reached the 30th anniversary of this fatwa and Rushdie has thus far survived its verdict, Akyol reminds us that it is still in force.

But his essay’s subject is broader than this particular event. In the first instance, it concerns the general question of blasphemy, that is, language insulting to pieties, and the great power that this charge has among contemporary Muslims. But this question has a still broader general import. It bears upon the relationship between contemporary Muslims, their states and societies, and modern liberal, democratic ways and norms. This is because the latter have as their touchstone freedom of speech—absolute freedom of speech, including the freedom to blaspheme.

As a result, Akyol cannot help but raise, in diverse ways, the question of whether contemporary Muslims can, should, or will adapt to or adopt modern ways and norms, a question which, as he notes, has been on the table for well over a hundred years, dating at a minimum to the days of Muhammad Abduh in the 19th century. To explain the issues involved in the Muslim perspective on blasphemy, he is obliged to discuss two aspects of it: first, the actual, technical status of blasphemy under Muslim law, as expounded by the five official schools of Muslim jurisprudence; and second, the more general role that “honor” and “shame” play in the Muslim sensibility as a whole.

The Iranian Revolution Turns 40

In all these respects, Akyol has given us a fine introduction for non-Muslim readers, however necessarily compressed, to the centrality of blasphemy and the issues it raises—issues that have often been at the center of tensions, not to mention conflict, between Muslims and non-Muslims. He goes beyond mere exposition to consider ways in which circumstances may or may not change in the future.

Thus Akyol has presented us with very large matters to deal with. Where to begin? Perhaps it is best to begin where he does, with the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and the Islamic Republic of Iran. For this month marks not only the 30th anniversary of Khomeini’s fatwa, but the 40th anniversary of Khomeini’s revolution and founding of the radical Shiite Islamic Republic.

Of course, and as Akyol makes clear, over the last 30 years it is not only Shiites but Sunnis who have pronounced denunciations of alleged blasphemies and sought to effect their punishment. Among those he cites are the murder of 12 employees of the French satiric magazine Charlie Hebdo in 2015 and the furor in Pakistan over the acquittal of Asia Bibi, a Christian, on blasphemy charges.

But one may say that Khomeini and the Islamic Republic took the lead in promoting the issue of blasphemy and have continued to try to claim the mantle of leadership in this regard. Thus some attention to Khomeini’s intentions in founding both a radical Shiite movement and a radical Shiite state, as well as his ambitions for both, may shed more light on the issue of blasphemy and its wider implications.

Indeed it does, for the radical Shiite movement that Khomeini created was a direct response to the most fundamental fact of Islam’s recent history: the enormous decline of Muslim political and military power around the world and, as important, the attendant decline in Muslim global prestige and honor. This decline, which occurred over the last three centuries, came against the background of a period of some 1,000 years during which Muslim polities were the predominant ones in the world by a very large margin. During this earlier period, Muslims could and did take satisfaction from the renown and glory to which Islam laid claim.

The great decline, which might be said to have reached its absolute nadir after the First World War with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the last great Muslim political power, could not help but be disappointing, in ordinary ways, to Muslim feelings and a wound to Muslim pride. But the meaning of this trauma was deepened by the fact that prior Muslim success and glory were understood to be a vindication of Islam’s claim to be the final dispensation that God had made for the whole world and the whole of humanity.

The “Rule of the Jurisprudent”

Khomeini (1902-1989) set about to remedy this situation. He and his radical Shiite disciples were not the first modern Muslims to do so. They were preceded by radical Sunni Muslim leaders and their movements, whose ultimate goal was to establish a new and powerful “Islamic State” that would restore Muslim prestige by contesting for power with the contemporary non-Muslim order of the world. But despite the numerical superiority of Sunnis among the world’s Muslims, Khomeini and his successors proved to be relatively more successful in achieving their goals and emphatically more direct in their hostility to the existing global order.

On the one hand, Khomeini managed to overturn a secularized modern regime in a Muslim-majority state, the regime of the shah of Iran, and to create a new “Islamic State.” In doing so he could congratulate himself on having “defeated” the Western forces that supported the shah. He also managed to overcome the opposition of mainstream Shiite tradition (of which he was originally an exemplar) to an emphatically Islamic “political” project. He did so through the promulgation of a new theological/political teaching, the “Rule of the Jurisprudent,” and the concrete embodiment of it in his new “Islamic Republic.”

On the other hand, Khomeini’s success supported his ambition to lead the Muslim world as a whole to “export the revolution.” His was a deliberate assault on the existing international order, and on “Global Arrogance,” the contemporary Iranian term for the United States—the creator and leader of that order, whose arrogance consists in the very presumption to lead the world in place of Islam, its proper leader.

It may be true, as some have suggested, that Khomeini’s fatwa against Rushdie was a tactical move designed to address the temporary weakness of the Islamic Republic after its eight-year war with Iraq. Nevertheless, the attack on blasphemy was and is the natural complement of the sensibility that informs contemporary radical Muslim movements, Sunni as well as Shiite, as well as a sensibility that affects Muslims more generally. Given the general circumstances of Muslim decline, it is natural that blasphemy and the disrespect it conveys should have become a specific focus.

Honor and Shame

It is somewhat difficult for non-Muslims to appreciate this sensibility, which Akyol shows in his descriptions of the hostile reaction to Rushdie’s novel as a form of “religious nationalism” that is, as he says, a product of the alienation and humiliation many Muslims feel living within the modern world. Of course, in the first instance this is because non-Muslims are hardly likely to share Muslims’ preoccupation with their relative status in the world, or what my friend Ambassador Husain Haqqani has termed Muslim “longing for past glory.”

But Akyol adds a further consideration: a difference in attitudes regarding “honor” and “shame” as such. This, he says, is a difference not only between Muslims and non-Muslims but between “East” and “West.” In the “East,” and certainly among Muslims, honor and shame play, as a matter of cultural tradition, a very great role, in matters both big and small. In the “West” they do not. This seems to me to be true and important.

It is of course the case that people in the West still seek to have honor and to avoid shame. Indeed, we sometimes accord people honor: for example men and women in our armed forces, and people of distinctive achievement in various fields of endeavor. But we are not obliged to. In Western societies, there is something that trumps honor: freedom. We often feel obliged (with however much irritation and controversy) to accept, if not like, insults to things we and others hold dear—to our our flags, our anthems, our heroes, even to our religious beliefs. We may hope that a deeper and broader reflection upon freedom may lead to an appreciation of its higher and fuller expression in dignified behavior, the dignity of a free person. We may even try to promote such an understanding. But we are not allowed to dictate it.

Moreover, this inclination to privilege, if necessary, freedom over honor or respect is embodied in our laws: laws that uphold the rights to freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom of assembly, and ultimately the full panoply of individual rights that are the foundations of liberal democracy and the institutions that are meant to protect them and give them expression.

As Akyol indicates, the situation as regards Muslim law is altogether otherwise, irrespective of the particular school of Muslim law to which individual believers adhere. Disrespect in the form of blasphemy is completely forbidden. Moreover, Muslim law, as well as ancestral custom, privileges certain understandings of honor in other matters—for example, family law and interactions between families.

This tension between honor and freedom, to which Akyol leads us, appears to be the heart of the matter.

The differences between Muslims and non-Muslims in this regard would not matter if two circumstances obtained: first, and most obviously, if Muslims and non-Muslims could and did lead completely separate lives according to their own understandings of the relationship of freedom and honor; second, if Muslims in their separate existence were entirely content with their lot—content with the privileged status of honor and the subordinate status of freedom, but also content with a diminished place in the world.

But neither of these circumstances obtains in the contemporary world. Large numbers of Muslims are citizens of Western countries. Moreover, the world is now too much, as we say, interconnected for Muslims and non-Muslims to lead completely separate lives. Nor are many Muslims, radical or otherwise, content with their diminished status in the world.

“Friction,” as Akyol writes, “between the West’s commitment to free speech and Muslims’ aversion to blasphemy” is unavoidable and “begs to be addressed.” He closes his essay by trying to address that task and its requirements.

Akyol would like to place part of the burden on non-Muslims who might make “Muslims feel at home in the modern world rather than being ‘otherized’ by that world.” But his procedure implies, and rightly so, that it is Muslims who largely insist on their “otherness.” It is therefore quite appropriate for him to focus on the necessity for and prospects of internal Muslim reform, beginning with Muslim jurisprudence and the foundations upon which it rests, namely the Qur’an and the Sunna of Muhammad.

Rereading, Reinterpreting, Contextualizing the Sacred Texts

Such reform efforts have by now a long history, and Akyol cites important figures in these efforts. He also offers examples of “reformist” arguments or interpretations, beginning with the Qur’an and the Sunna, some of them of his own. A more general mode he delves into is “historicist,” in which the objective is to “contextualize” the Qur’an and the Sunna. I am in some doubt that the jurisprudential and historicist modes are simply distinct—at least to judge by the person Akyol cites as the leading “historicizing” scholar, Fazlur Rahman, who happened to be my teacher. For I understood Professor Rahman to have argued that the Qur’an manifestly expressed itself “contextually” and therefore pointed to the future need for interpretation from the beginning.

However that may be, and despite the long history of reform, Akyol indicates that such efforts are far from coming to fruition, comparing as he does the present state of the Muslim world to that of the West in 1689, when John Locke published his Letter on Toleration. One may hope that such efforts will accelerate.

In the meantime, one might pursue a complementary path that Akyol implicitly suggests when he concludes by invoking the term “dignity.” Such a path entails a rethinking of the meaning of “honor,” a meaning of which free men and women could be proud. For reasons described above, this would not be a bad idea for non-Muslims, either, especially Westerners. Perhaps in this way, Muslims and non-Muslims could begin to find some common ground.