The Islamic State in Somalia has received much attention in the global media over the last few years. U.S. intelligence analysts reportedly believe that the leader of the Islamic State’s Somalia outfit, Abdulqadir Mumin,has become the new overall leader of the Islamic State.1 In Sweden, police arrested the so-called Tyresø gang, consisting of four individuals, in May 2024 for planning terror attacks and having ties to the Islamic State in Somalia.2 Prior to that, in 2018, police arrested former Islamic State member Omar Mohsin Ibrahim in Bari, Italy, allegedly for planning a terror attack against St. Peter’s Basilica.3

The Islamic State in Somalia also has regional significance. Its decision to reorganize its global chain of command in 2018–2019 resulted in the establishment of the so-called al-Karrar office in Somalia. The Karrar office has a regional responsibility to distribute funds to other Islamic State provinces in East and Central Africa. The office has become a financial hub for money transfers to several other provinces, allegedly including the Khurasan Province in Afghanistan, which is one of the deadliest and most internationally oriented of the Islamic State’s branches. In 2023, the Washington Post printed an article suggesting that the Islamic State in Mozambique sent battlefield reports to Somalia and that funds from (or transferred through) Somalia saved the Islamic State’s Central Africa Province in 2019.4 The many foreign fighters in the Islamic State in Somalia, as well as its alleged contacts with the Shia-majority Houthi armed group in Yemen, have also made headlines.5

Yet, within Somalia, the Islamic State has never held significant territories beyond small hamlets around the Cal Miskaat mountains in a remote area of Somalia’s Puntland state, where it relies on support from one local clan. The Islamic State in Somalia is thus both “global” and “local,” both foreign fighter-based and clan-based.6 To follow Adib Bencherif, global-local interaction takes place as a “dialectical process and as a sequence of events and actions occurring in intertwined layers.”7 This article studies how local factors such as geography and local trade patterns made the Islamic state more global, and how, in turn, global impulses drove the small group that became the Islamic State to split from Somalia’s al-Qaeda affiliate, al-Shabaab. Meanwhile, local clan protection has enabled the Islamic State to survive in Puntland. This article also introduces a third level, a regional level, by illustrating how regional refugee patterns have generated foreign fighters. The Islamic State in Somalia has thus had a global impact even as it reassembles, in some ways, a group of Somali “hillbillies.” This contradiction might be less drastic than observers often believe if we understand that local factors can enable forms of global agency.

Origins: Global Ideas, Local Clans

Somalia’s Islamic State is a product of global ideas fertilized by a local context. The original Islamic State expanded rapidly by taking territories in the Levant and broke with al-Qaeda in 2014, creating a new global jihadist outfit.8 Its rapid expansion and its belief in eschatology and militarism made it a successful rival to al-Qaeda, projecting an image of success that al-Qaeda lacked at the time. Meanwhile, the Islamic State and its affiliates actively wooed the longstanding Somalia-based insurgency and al-Qaeda affiliate Harakat al-Shabaab al-Mujahideen (“the movement of youth jihadists,” better known as al-Shabaab). For example, they waged an outright media campaign against al-Shabaab aimed at getting them to switch sides.9 Al-Shabaab’s problems in 2011–2014 may have made joining the Islamic State more appealing at the time. Al-Shabaab had gone through several years of setbacks, losing territories since 2011, suffering an internal purge in 2013, and facing the loss of its leader in 2014.10 Moreover, and often overlooked, the group had not been clear in its condemnation of the Islamic State prior to 2015. This ambiguity may have indicated either that its leadership had secretly considered joining the Islamic State or that it knew Islamic State sympathizers were within its ranks and wished to maintain unity by neglecting the matter for as long as possible.11

However, al-Shabaab’s internal security units quickly killed the various mid-level leaders who eventually declared their loyalty to the Islamic State (none of the top al-Shabaab leaders defected). The Islamic State’s attempt to take over al-Shabaab and/or establish a viable alternative to the latter thus failed. Some Islamic State loyalists might have survived in Somalia’s capital, Mogadishu, and conducted sporadic extortion in the city, but even this was limited.12 It was rather in Puntland, a northeastern province of Somalia, far away from the central territories of the al-Shabaab, that the Islamic State established a more permanent presence. This minimized the threat from al-Shabaab, which had a much weaker presence in the area in which the Islamic State grew than in central and southern Somalia. It is not a coincidence that the Islamic State indeed decided to establish its al-Karrar office here: The part of Puntland where the Islamic State established its province, in the remote Cal Miskaat mountains, offered survival to the new group. It offered security against both Puntland’s security forces and al-Shabaab, while its proximity to the strategic coastline along the Gulf of Aden provided ample income-generating possibilities and logistical advantages for an organization loyal to a Middle Eastern insurgency.

The Puntland State of Somalia is an autonomous federal state that enjoys considerable self-rule and shuns the influence of the central authorities in Mogadishu, but it has not declared full independence from the country (unlike Somaliland, located to Puntland’s west). Puntland was formed in 1998, but its roots go back to 1993.13 Over the years, there have been several clan-based state-like entities in the area that today constitutes Puntland. The most famous was the Majeerteen sultanate, the political entity closest to functioning as an independent local state in nineteenth-century Somalia. The northeastern part of the country has also historically had strong maritime ties to Yemen, Oman, and the wider Middle East. Mercenaries from Yemen played a considerable role in the history of the Majeerteen sultanate, and political leaders from northeastern Somalia at times fled across the Gulf of Aden to Yemen.14 The region is today a hub of human smuggling, where refugees seek to migrate to the Middle East (and, when the civil war in Yemen grows intense, also refugees going in the opposite direction), alongside maritime trade between Somalia and Yemen and the wider Middle East. Puntland’s rugged terrain also makes it ideal for piracy, illegal smuggling, and insurgency.

Puntland is not a militarily weak actor. While its security forces, the Darawisha, are not large in number or capabilities, its strength lies in its popular support among specific subclans of the Majeerteen (itself a clan of the larger Darod clan family), particularly the Omar Mahmoud, Osman Mahmoud, and Issa Mahmoud subclans (although there is considerable rivalry between these groups when they do not face an external threat).15 Other clans in the area include the Dhulbahante and Warsangeli clans (separate from the Majerteen but related to them by membership in the Harti subgroup of the Darod), which have at times affiliated themselves with Puntland. Voices within these clans have also argued for their own independence and even, in the past, for a union with Somaliland.16 There are smaller clans with less influence on Puntland politics, such as the Ali Suleiman subclan of the Majerteen, which is marginalized in the province, though its members play a major role in maritime commerce as well as piracy and illicit trade.17 These clan dynamics and the geography of Bari province in Puntland were important factors that first drew the Islamic State to the region in an effort to protect itself and explain why the Islamic State has survived in the north of Somalia and not in the south.

The Islamic State group emerged from the northern part of Somalia’s al-Shabaab. While in southern Somalia, al-Shabaab initially expanded slowly but steadily out of a small group based in Mogadishu, in the north it had entirely different origins: the Warsangeli clan, more specifically its Dubya subclan. It resulted from animosities toward Puntland’s oil exploration in the mountains of northern Sanaag, located slightly west of the present-day core areas of the Islamic State. Arms smuggler and businessman Said “Atom,” who has deep ties to smugglers in Sanaag, established the group as a small militia in 2010.18 Over time, Atom developed extensive ties with al-Shabaab, partly due to his arms smuggling.19 He was a pragmatist whom al-Shabaab had to convince to remain loyal at times. Al-Shabaab even sent two emissaries from Mogadishu, Yasin Kilwe and Mohamud Mohamed Nur Faruur, to Puntland to ensure Atom’s loyalty.20 Indeed, it might have at first similarly dispatched Sheikh Abdulqader Mumin, the founder of the Islamic State in Somalia, to join the northern group as an emissary like Kilwe.21 Upon his return to Somalia in 2012 after several decades as a refugee in Sweden and the United Kingdom (where he came under surveillance for his incendiary preaching and ties to homegrown British jihadists), Mumin gave a fiery introductory speech that al-Shabaab media networks broadcasted, illustrating his role in the group at the time and specifically as an ideologue conveying ideological messages to the organization and its sympathizers.22

The arrival of Mumin might have helped al-Shabaab to expand eastward within Puntland into other clan areas, including the Dhadaar area that Mumin’s own clan, the Ali Suleiman subclan of the Majeerteen, inhabited. The group also developed ties with the business community in Puntland’s major port city of Bosaso, including the prominent businessman and smuggler Isma’il Hassan “Kutuboweyne,” also from Mumin’s clan. Another top northern al-Shabaab official from Mumin’s clan was Muhamed Ismael “kini kini.” In 2012–2013, the organization established a 50-to-80-man outfit operating in the Ali Suleiman–inhabited parts of Bari. Their leader was Abdirahkim Dhuqub, Mumin’s cousin, who brought with him other notable al-Shabaab leaders from the Ali Suleiman, such as Abdikarim Ahmed Ibrahim.23

This small Ali Suleiman component of al-Shabaab enjoyed many advantages in Bari. First, the terrain was well suited to guerrilla warfare. Mountain ranges and limited road access made it harder for Puntland to conduct counterinsurgency campaigns. Second, the members of this unit were probably protected by members of their clan, the Ali Suleiman. The clan had long opposed the Puntland authorities, who had often excluded them from the top positions in government.24 Somali clans tend to protect their own members when they are threatened as individuals. This does not mean that Ali Suleiman protected or protects al-Shabaab or the Islamic State. However, it has often protected individual clan members in these organizations who may have been fleeing or trying to hide from the government (in Somalia, a jihadist on the run will often turn into a clannist, fleeing first to his clan for protection). In some cases, clan militias will fight to defend such clan members. This does not mean a clan will protect jihadists at all costs, however. The clan will yield if there is a threat to the security of the clan as a whole or if the military odds against the clan are too large. Moreover, some individual clan members might betray other clan members if they benefit enough from doing so. The importance of clan ties does, however, mean that an individual jihadist from a local clan will have some protection and warning from his clan members and have interlocutors in the security forces through fellow clan members serving in these institutions. This is especially true if the clan as a whole is skeptical of the security institutions, as the Ali Suleiman clan has been. It meant that Puntland security forces could face costly resistance when intervening in Bari (most clans in Somalia possess arms), especially if they had failed to negotiate with local clans to get a “permit” for offensives. Finally, the small Bari offshoot was far from the Puntland authorities’ main offensives against the rest of al-Shabaab’s northern group, which was predominantly in Sanaag. By 2013, it seemed that Mumin often based himself in the Bari region, among his own clan.25

The northern al-Shabaab encountered serious problems between 2012 and 2015, as they were under pressure from Puntland’s military offensives and from tensions within the group in the Sanaag mountains. Their old leader, the not-so-ideologically-conformist Said Atom, in the end defected from the organization. It was in this context that Mumin publicly declared his loyalty to the Islamic State in June 2015.26 The most prominent Ali Suleiman leaders in al-Shabaab, Mahad Moalim and his cousin Abdihakim Dhuqub Ali, also joined the new group in the following months.27 Indeed, all the leaders of the largely clan-based al-Shabaab group in Bari joined the Islamic State in 2015, when the splinter faction first emerged. At the time, the new group might have enjoyed logistics support from legendary Ali Suleiman pirates, including Isse “Yulhowe” and Mohammed Mussa Saeed “Aargoosto.”28 (Some sources also stipulate that the former paid a percentage of his ransom to al-Shabaab even as he smuggled supplies to the Islamic State, but this writer finds this unlikely; Yulhowe was simply too strong at the time.29

Much as it had been for the small unit of then-al-Shabaab fighters, the Bari province was filled with opportunities for the new Islamic State group. The area is both remote and hard to reach for Puntland forces yet also globally connected through its extensive smuggling routes. Bosaso, the largest city in the region, has strong historical trade ties to Yemen, Oman, and the wider Middle East. Militarily, the new Islamic State–affiliated group in Bari faced the weakest part of al-Shabaab, the weak and disunited northern group based predominantly in neighboring Sanaag. The Bari group simply had better chances of survival than any nascent Islamic State movement in southern Somalia. In the end, several Islamic State sympathizers among al-Shabaab based in the south had to flee to this relatively safe location in Bari, to the protection of their fellow jihadists, who in turn enjoyed local clan protectors.30 The state of affairs became even more advantageous for the Islamic State group when the Bari governor of Puntland, Abdisamed Gallan, a member of Mumin’s clan, went into open rebellion against Puntland in 2016. The rebellion was to the Islamic State’s advantage because it distracted Puntland security forces and increased clan loyalty among the Ali Suleiman, who now saw their clan, inclusive of the Islamic State leaders, as under threat from Puntland.31

Al-Shabaab tried to kill off the Bari group early on, as they did (more successfully) to other Islamic State cells in the south.32 It tried to reinforce its northern component by landing its Khalid bin Walid brigade on a beach in south Puntland in 2016.33 But this unit failed to even reach the battlefield; the Puntland militia (Darawisha) defeated it en route, illustrating the advantages of the Islamic State’s distance from the core areas of al-Shabaab. The Puntland Darawisha and the clan militias loyal to it were also strong, yet this coalition faced problems in areas where they lacked the loyalty of the local clans, as in the Ali Suleiman areas of Bari. Puntland’s security forces, in many ways, thus acted as a “protection belt” for the Islamic State, hindering al-Shabaab from projecting its power northward but still unable to vanquish the Islamic State itself due to terrain and clan-related issues.

The remote nature of coastal Bari areas also enabled the small group to take control of smaller hamlets, the most well-known being Qandala, a former smuggling and pirate hub on the northern Puntland coast, which they took in 2016. The city had little Puntland security force presence (if any at all) and was an easy target.34 The international press made much of this early victory by the emergent Islamic State faction and indeed probably overestimated Qandala’s importance. Yet, it took time for Puntland to launch its counteroffensive. Puntland had to actively work to create alliances with local Ali Suleiman leaders to avoid clan conflict, and Qandala’s remoteness meant it was hard to reach. Some of the more famous Ali Suleiman leaders, such as the infamous pirate Yulhowe, actively fought the Islamic State during this offensive after the Puntland government paid them to do so, a pattern not too unlike classical European privateering during the golden age of piracy. Yulhowe, mimicking the historical pattern of pirates and privateers, followed financial gains and later resorted to aiding the Islamic State, again for his own profit.

All in all, the northern group enjoyed the protection of geography and clan factors. One may say the group was a product of foreign influence (through the ideology of the Islamic State, which gained international attention due to the startling successes in the Levant, and possibly through the Islamic State’s specific media campaign targeting al-Shabaab) that nevertheless survived only because of local dynamics. The Islamic State’s Somalia branch thus had its roots both in clan politics and in global jihadist ideology.

Creating Stable Income Sources

Though it was small and new, al-Shabaab already had a blueprint for income generation, namely its well-tested system of extortion of the Somali business community. The group’s geographic position made extortion potentially quite profitable. Bosaso is, as mentioned previously, a key city in both legal and illegal trade between the Middle East and the Horn of Africa. A suicide bombing of the Juba Hotel in Bosaso in 2017 was a major milestone for the new organization, sending a clear message to the city’s businessmen to “pay or die.”35 Subsequent assassinations were forceful reminders that helped generate protection money. Abdirahman “Fahiye” Isse Mohamud, whom Puntland authorities also accused of planning the initial 2017 attack, oversaw the racket.36 Fahiye hailed from the small Dashishle clan that dominates the area around Bosaso. Extortion of the city’s business community enabled the group to become relatively profitable given its size. However, it might also have contributed to the development of internal rivalries over money and control of extortion rackets. At one point, a group around Abdirashid Luqmaan (from a local subclan of the Leelkase clan) challenged Mahad Moalim, Abdihakim Dhuqub, and Mohamed Ahmed “Qahiye,”37 which led to the killing of Moalim.38 Nevertheless, older leaders such as Fahiye and Mumin held their positions during this internal tussle.39 In fact, the showdown might have broadened the clan base of the organization by removing some Ali Suleiman leaders, though all the top leaders remained from local clans in central, northern, and northwestern Bari and remain so today.

There were clearly also Islamic State activities in southern and central Somalia in 2017 and 2018. The Islamic State took responsibility for more than 50 assassinations and five improvised explosive device (IED) attacks in Mogadishu and the nearby suburb of Afgoye in this time.40 Three men went on trial for the attacks, including Jama Hussein Hassan, who the Somali authorities claimed the Islamic State had sent from the north to plan the attacks.41 Yet, the group’s attempts at extortion in Mogadishu appear to have been less successful than those in Bosaso, and its attempts to gain finances from Mogadishu are likely limited today, if not nonexistent.42

Nonetheless, the relative wealth the small organization gained from its activities in Puntland might have been one of the factors prompting the Islamic State to eventually give the Somalia branch more of a leadership position within its global network, for the simple reason that the Islamic State in Somalia had the money to reinvest elsewhere.

Going Global from the Mountains of Bari?

On July 27, 2018, the Islamic State officially designated the Somali group a full “province,” which it announced in that week’s edition of its official al-Naba magazine. The following year, in December 2018, Somali national Omar Mohsin Ibrahim was arrested in Bari, Italy, allegedly for planning an attack against St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City as well as for other terror attacks.43 The steady growth of the Islamic State in Somalia, mostly in terms of finances but also in manpower and international outreach, quickly attracted the attention of the United States, which started to launch air strikes against the organization.44

The biggest change for the Islamic State in Somalia came with the global reorganization of the Islamic State in 2018–2019, and with it the establishment of regional offices. All in all, the organization established nine regional offices, basing one, Maktab al-Karrar, in the small Puntland chapter of the group.45 The reorganization meant a still small and largely clan-based group would hold global responsibilities. The Islamic State made the Somali group responsible for overseeing its activities in the Central African (based in the Democratic Republic of Congo) and Mozambique provinces. Money transfers from the Islamic State might have contributed to the Somalia province’s coffers, but the aforementioned extortion money, flowing steadily from Bosaso and other Puntland cities, was probably much more important for the province’s longevity.46 In 2022, the U.S. Treasury claimed that the organization generated nearly $2 million in the first half of the year alone, a relatively good income for such a small group. The Somalia province also lacked the more costly governance structures that al-Shabaab had developed farther south, meaning it was a cheap organization to manage compared to its rivals.47 The al-Karrar office and Mumin himself thus emerged as key financial players in East Africa and even beyond, handling modest but important financial streams48 from their base in Buur Dexhtaalin Bari.49

The geographic location of the group, as well as its increased importance and media prominence due to the establishment of the al-Karrar office, might have contributed to the Islamic State’s ability to recruit foreign fighters. The increasing number of foreign fighters joining the Somali branch contributed to an increase in the group’s size from an estimated 350 fighters in 2019 to 600–1,500 fighters in 2024.50 Drawing on various sources, Caleb Weiss and Lucas Webber find that Moroccans, Ethiopians, Yemenis, Tunisians, Tanzanians, Kenyans, and Sudanese are among the nationalities that have joined the group.51 Similarly, in 2024, one of the ethnic Swedes in the Tyresø group attempted to join the Islamic State in Puntland, although he was stopped in Turkey.52 The Islamic State in Somalia actively tried to recruit foreign fighters, especially targeting neighboring Ethiopia.53 The Puntland authorities claimed that one such Ethiopian, Abu Albara Al Amani, became the head of operations and possibly even the second in command of the organization before his death in 2023.54 Several foreign fighters have also defected to Puntland, confirming reports of the relatively large inflow of such fighters.55

Yet, the flow of foreign fighters was heavily influenced by local factors, such as the role of Bosaso as a trading and smuggling hub. Human smuggling routes enabled easy access for foreign fighters, and connections with Yemen eased recruitment in that country. Bossaso was, and is, the end of human smuggling routes running from the various countries in East Africa and the Horn of Africa into the Middle East. In fact, analysts have recorded the passage of 47,800 individuals through Bosaso on their way to Yemen and the Arabian Peninsula in 2023 alone.56 Many of them end up in refugee camps in Bosaso, waiting in transit for months if not years. The majority of these refugees are Ethiopian, perhaps explaining the Islamic State’s focus on Ethiopia in their propaganda efforts.57 A local source claimed that while some foreigners joined the group as experienced fighters, others may have joined due to the pressure of their circumstances and vulnerable status as refugees.58 As the International Crisis Group has stated, the Islamic State may pressure refugees into joining, or they may join because of poverty.59

The influx of foreign fighters might be one reason the group was able to finally stop al-Shabaab’s periodic attacks against them in the Cal Miskaat mountains after intense fighting in 2022 and 2023. These fighters may have helped the Islamic State develop sufficient manpower to confront al-Shabaab far from the latter’s main bases in southern Somalia.60 Yet despite the growing number of foreign fighters in its ranks, Fahiye and Mumin have led the group for a time (and still do, according to local sources). The group appointed a new head of finance, Abdiweli Mohamed Yusuf “Waran-Walac,” in 2019.61

The Islamic state in Somalia was, by 2024, a strange hybrid, partly clan-based in its recruitment but also including a large number of foreign fighters. Similarly, while still small compared to al-Shabaab, it had outsized financial strength owing to its successful extortion practices. The Islamic State was still tumbling around in remote mountains but was also able to build more permanent bases by this time in the remote Jecel Valley (Togjaceel) area of Bari. Yet, for all its apparent growing influence, the group remained vulnerable in many ways.

Not So Great After All?

Reports regarding the Islamic State in Somalia and its al-Karrar office are often overblown. Regarding foreign plots, the accusations against the Tyresø group for a planned attack on the Israeli embassy in Stockholm failed to hold up in court.62 In the case of Omar Mohsin Ibrahim's plans to attack the Basilica of St. Peter, it seems Mohsin had already broken off his relationship with Mumin by the time he was in Italy and planned the attack on his own, without the guidance of the Islamic State.63

As for the 2024 reports that the U.S. intelligence community now suspects Mumin has become the overall leader of the Islamic State, there is reason for skepticism. According to the Islamic State’s own understanding of its movement as a caliphate, any leader of the group must be from a tribe that can trace its lineage to the Quraishi of the Arabian Peninsula (of which the Prophet Muhammad was a member). Because of this and the small size of the Islamic State in Somalia compared to the other Islamic State provinces in Africa, it is doubtful that Mumin is the global leader of the group.64 Moreover, several factors would explain the large number of foreign fighters in the organization apart from any plans to move its global leadership to Somalia. The geographic position of Puntland as the hub between the Middle East and East Africa and the center of regional refugee streams is sufficient to account for the influx of foreign fighters.65 Second, because of the income-generating capacities of al-Karrar, in addition to some of the attention the Somali province has received in the Islamic State media ecosystem, this province has likely appeared attractive to foreigners. It is nevertheless important to underline that the province receives much less attention than the other Islamic State provinces in Africa in al-Naba magazine, the Islamic State’s only remaining official periodical. Al-Naba has flagged Africa as a whole as a new and successful “field of jihad,” partly to encourage non-Africans to join the African groups, which may have likewise motivated some of the foreign fighters who joined the Somalia province.66

Puntland’s Campaign in the Valleys (Operation Lightning)

The other reason to mitigate some of the fears about an Islamic State resurgence in Somalia is that the Puntland authorities launched a relatively successful counteroffensive against the Islamic State that began on December 31, 2024. As is typical of the Puntland Darawisha, they needed to save up ammunition over time to prepare for offensives due to low funds. Moreover, they typically need to gain a form of local clan consensus in the areas where they want to undertake a campaign, a process that takes time. The wait is worth it, as negotiating with local clans prevents additional conflicts from breaking out and usually results in additional clan militias joining the Puntland forces, acting as a force multiplier. The above factors likely explain why the Puntlanders waited so long before launching an offensive against the Islamic State, both when preparing their 2025 offensive and before the offensive against Qandala in 2016.

Puntland forces hold several strategic advantages over the insurgents. The United States has been extensively involved in attacks against the Islamic State in Somalia, including since President Donald Trump took office. This an example of American engagement in a period when the U.S. government’s stated position is often to disengage from conflicts around the world.67 Puntland also has a long-standing strategic relationship with the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The Emiratis conducted drone strikes against the Islamic State during the 2025 campaign68 and have also trained the Puntland Darawisha and coast guard, the latter having received regular support and the deployment of Emirati advisers since 2010.69 However, there is also a cost to having the Emiratis as allies: UAE activities in the region are increasingly alienating the federal president of Somalia, who fears that Puntland might move toward more autonomy or even independence. The UAE’s presence in Puntland inevitably creates rumors in Mogadishu, including speculation that the UAE funds the Islamic State. Such conspiracy theories can have an impact on Somali politics. Notably, the main federal security force, the Somali National Army (SNA), did not contribute to Puntland’s offensive in 2025. The SNA is currently preoccupied with attempting to contain a heavy offensive by al-Shabaab in central Somalia, though there might also be political reasons for Somalia’s lack of support for Puntland: relations between the two governments are fraught.70 Nevertheless, Puntland Darawisha, with the support of Emirati and U.S. drone strikes, performed quite well in the 2025 offensive, which it officially launched on January 2.

The main thrust of the Puntland Security Forces offensive focused on the Islamic State’s bases in the Cal Miskaat mountains, in the center of Bari. The Darawisha and its allies managed to medevac soldiers through the use of a helicopter while extensively employing drones in its operations.71 The Islamic State similarly relied on the deployment of armed drones, suicide bombers, suicide-vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (SVBIEDs, aka suicide car bombs), and extensive use of caves to store supplies and men as counter-strategies in an effort to disrupt and stall Puntland’s campaign.72

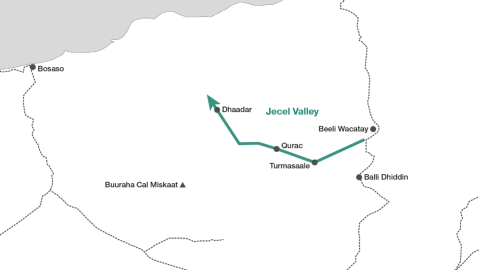

The Puntland forces pushed through the Jecel Valley (Togjaceel) within the Cal Miskaat range, deploying from the rough road between the northern coast and Iskuban to fully clear this remote area. There were also thrusts in the nearby Miirale valley. The objective of Puntland forces in the Jecel thrust was to destroy the main Islamic State bases in Dhaadaar and Buur Dexhtaal as well as the smaller bases on the route there. The Islamic State responded to this campaign with frequent attacks by drones armed with simple munitions like grenades. A Puntland officer, Jiib Gurey Bootaan, at one point destroyed an enemy drone by grabbing it by hand and smashing it on the ground.73

Figure 1. The Cal Miskaat mountain range in Somalia’s Puntland state (Source: Author)

Figure 2. The direction of Puntland security forces’ advances through the Cal Miskaat mountain range in early 2025 (Source: Author)

The Islamic State’s resistance was selective: In many instances, fighters withdrew without putting up a fight, while in other locations, significant battles occurred. For example, on January 24, Puntland fighters captured Turmasaale after intense combat with the insurgents, perhaps constituting the third-largest battle of the campaign in terms of casualties.74 The battle of Dharin and Qurac farther up the valley, February 4–5, was the second-largest of the campaign according to figures from the Puntland government, which claimed to have killed 57 Islamic State fighters at the cost of 15 Puntland soldiers.75 In the last major battle of the campaign, the Islamic State counterattacked on February 8 around Haraaryo, and Puntland authorities successfully repelled the attack and killed 70 Islamic State fighters.76 By late February, the morale of the Islamic State fighters seemed to break, and Dhasaan and Dhaadaar fell within a few days. Puntland captured Buur Dexhtaal in early March.77 With that, all the larger (known) bases had fallen, although there was a failed counterattack against Dhasaan on May 3, and U.S. drone strikes likewise continued against Islamic State targets into early May. Sporadic fighting has continued as of this writing in Miirale as well as the Curaar valley, but these skirmishes have so far been limited.

The Islamic State in Somalia Today

The Puntland offensive has culled the Islamic State in Somalia but has not defeated it. Authorities captured many fighters, particularly foreign fighters, after they fled their bases.78 (The considerable number of captured foreign fighters has had the broader societal effect of creating animosity toward foreigners and refugees among the Puntland population.) Local clan elders mediated a six-day amnesty for Islamic State fighters at the end of the campaign that contributed to the surrender of additional fighters as well.79

Puntland authorities claim that 180–200 Islamic State fighters were killed in the recent 2025 campaign. This is a substantial victory. However, it also means 400–1,400 Islamic State fighters remain (although some might have been imprisoned or received amnesty), depending on which estimate of the prewar forces of the group one chooses to believe. The rugged terrain of Puntland will enable some of the remaining fighters to hide from Puntland’s drones and ground patrols as well as ongoing air attacks by Emirati forces. Neither Abdulqader Mumin, now over 70 years old, nor his second in command, Abdirahman “Fahiye,” nor the reported head of finance, Abdiwali “Waran-Walac” (still in his forties), has been confirmed killed or captured by Puntland authorities. All three are most likely still alive.

Some of the surviving members of the group might still defect to Puntland authorities. Local fighters may return to their clans—meaning that, under some circumstances, they could be activated by the Islamic State again, as Somali clans keep their own arms. It is an open question whether the culling has curtailed the Islamic State’s ability to extort money from the northern business community. The Puntland police prevented several bomb attacks in Bosaso during the campaign, which is encouraging. Such police activities are essential to stopping the Islamic State from continuing to generate income from the strategic port city. The struggle for extortion money in Bosaso is perhaps the most neglected battlefield in the fight against the Islamic State and yet perhaps the most important.80 Extortion money will enable the Islamic State to replenish its losses by recruiting from the large numbers of refugees in the city as well as recruiting poor locals who need jobs all over the Bari province. Whatever happens next, it is worth remembering that the Islamic State has proven more adaptable than many expected: In the course of their campaign, the Puntlanders discovered primitive facilities for producing missiles alongside evidence of a large number of foreign fighters.81

The current status of the province illustrates its major paradox. It shoulders large responsibilities for the Islamic State’s global mission and is located close to one of the region’s maritime hubs and the center of extensive illegal trade networks. Yet, its members are also stragglers dependent on moving and surviving in the harsh mountainous areas of the remote Bari province of northern Somalia. The organization will likely remain a strange mix of foreign jihadists and members of local, marginalized clans. Though it may have some global importance because of its management of financial streams and its geographical location, it will likely lack the number of fighters necessary to act as a major insurgency on the ground. The Islamic State in Somalia is, to a certain extent, a historic anomaly, a group of hillbillies with a form of limited global reach.