The Holy See’s 2018 provisional agreement with Beijing is failing, but the problems with the Vatican’s China policy did not begin five years ago. They stem from the 1980s, when the Holy See began pursuing dialogue with the Chinese Communist Party. The Vatican has capitulated more and more to keep that dialogue alive.

The capitulation has accelerated during Pope Francis’s papacy and under Vatican secretary of state Cardinal Pietro Parolin. Pope Benedict XVI, in a 2007 letter laying out fundamental principles for China’s Catholic Church, called the Beijing regime’s unilateral appointment of Catholic bishops “one of the most delicate problems” in Vatican–Sino relations. The provisional agreement was supposed to begin to solve it.

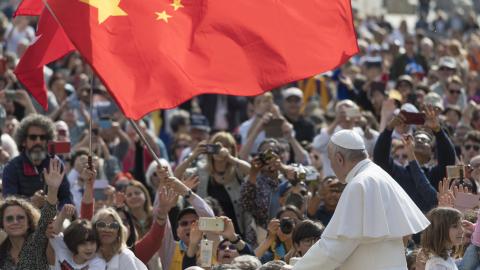

Five years after the signing of the agreement, though, the Chinese government continues to appoint bishops on its own. Pope Francis began giving his after-the-fact blessing to these appointments and over the past two years has done so routinely. No deal with Beijing was needed to obtain this result, but Vatican diplomats present it as a “remarkable” achievement in the long quest for “communion” with and “unity” among China’s bishops. They forget that the strategy undermines the pope’s “supreme spiritual authority,” as Benedict called it, to appoint bishops by delegating it de facto to a repressive atheist regime.

The Vatican adopted its policy of pursuing dialogue to counter Communist Party efforts to sever the Chinese Catholic Church’s ties to the Holy See. Those CCP efforts began in 1951 with the expulsion from Beijing of papal nuncio Antonio Riberi, his entire diplomatic staff, and foreign Catholic clergy. In 1955, after rejecting a Communist demand to lead a CCP-aligned church, Cardinal Ignatius Kung, then bishop of Shanghai, China’s most important diocese, was arrested, subjected to a show trial, given a life sentence, and imprisoned until his release 30 years later. In 1957 the regime established the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association (CCPA) as a government body that required from its members profession of their independence from the pope, and in 1980 it set up a Catholic Bishops Council, also independent. The Vatican has not recognized either of these entities.

Western criticism of the Vatican’s China policy has focused on its silence about human rights. It is true that the Vatican has been silent. The silence is similar to that of the Ostpolitik it practiced in Eastern Europe before Pope John Paul II took a more assertive — and successful — stance. Worldwide, Catholic bishops are expected to refrain from speaking publicly about China’s repression, particularly against the Catholic Church. Vatican diplomats try to promote this policy broadly, too. Monsignor Claudio Celli, then the Vatican’s chief China negotiator, criticized me for documenting the names of jailed Chinese bishops: In a side meeting at a Washington reception 20 years ago, he told me it could “hurt the dialogue” (while conceding that, as a lay Catholic, I had every right to do it). A long-term Vatican adviser on China who has nurtured relations with the CCP-endorsed Patriotic Church, Father Jeroom Heyndrickx, denied my recent request for the names of 17 Chinese bishops who, according to the Pontifical Institute on Foreign Missions, are being persecuted by the CCP. He said that he favors dialogue instead.

The Vatican is mum about other injustices, including the cases of lay Catholic Jimmy Lai, who was arrested and tried by authorities after the newspaper he founded was shut down, and of a thousand other political prisoners in Hong Kong; the genocide of Uyghur Muslims; the crackdowns on Tibetan Buddhists and Falun Gong; mass forced abortion and sterilization; forced organ-harvesting; indefinite detention without trial; and the refoulement of desperate North Korean refugees.

The principles in Benedict’s letter are nuanced and provide pros and cons for Chinese clergy to weigh when making very hard choices. But they have been selectively cited by Vatican diplomats and made to sound like Ostpolitik’s no-criticism, no-dissent rule. In 2018, Cardinal Parolin, the Vatican secretary of state, cited Benedict’s principle against conflict with legitimate civil authorities. As Hong Kong’s Cardinal Joseph Zen noted at the time, Parolin dropped Benedict’s caveat that “compliance with those authorities is not acceptable when they interfere unduly in matters regarding the faith and discipline of the Church.” Parolin quoted another Benedict principle, stating that the church must not “replace the State,” but he dropped the crucial clause: “Yet at the same time she cannot and must not remain on the sidelines in the fight for justice.” Zen said that in both instances, Parolin had lost “the balance of Pope Benedict’s thought.”

Some church officials have even promoted CCP propaganda. Before being disgraced and laicized, Cardinal Theodore McCarrick was viewed in Washington as a leading authority on China’s Catholics. In 2000, when he and I both served on the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, he gave a briefing in which he falsely asserted that Bishop James Su Zhimin — detained in 1996 for praying without CCP authorization — had been freed, was no longer a bishop, and did not need the commission’s help. New York’s Cardinal O’Connor helped me prove him wrong. Bishop Su never resurfaced and, according to the U.S. Congress, now ranks among the world’s longest-held political prisoners. Catholic News Agency reported that McCarrick has made eight trips to China, staying in a government seminary. In 2003 he became the first Western cardinal to visit China after a diplomatic dispute over the Vatican’s canonization of Chinese martyrs three years before; Monsignor Celli denied that McCarrick represented the Vatican even as McCarrick intimated that he did. Two years before the 2018 deal between the Vatican and Beijing, in an interview with the CCP outlet Global Times, McCarrick enthused about “the similarities” between Francis and Xi, which were a “special gift for the world.” He explained: “I see a lot of things happening that would really open many doors because President Xi and his government are concerned about things that Pope Francis is concerned about, . . . especially the ecology.”

Bishop Marcelo Sánchez Sorondo, former chancellor of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences and a member of the World Economic Forum, made headlines in 2018 when, referring to climate-change policies, he startlingly claimed that “those who are best implementing the social doctrine of the Church are the Chinese,” since Beijing “is defending the dignity of the person.” The Argentine monsignor added: “The economy” of China “does not dominate politics, as happens in the United States. . . . On the contrary, the Chinese . . . propose work and the common good.” In 2018, at the behest of longtime CCP Central Committee member Huang Jiefu, Sánchez Sorondo successfully promoted a proposal for the World Health Organization to create an advisory task force, focusing on the ethics of organ transplants, that would appoint Huang as a member. The task force was apparently intended to preempt an investigation into mounting complaints that China forcibly harvested organs from Falun Gong and Uyghur prisoners. At an international conference in 2017, Sánchez Sorondo had also, without independent evidence, defended Beijing against charges of forced organ harvesting, according to the pontifical outlet AsiaNews. Sánchez Sorondo’s controversial views found an echo in Laudate Deum, the October 2023 apostolic exhortation on climate change, in which Pope Francis criticizes the United States for having higher per capita emissions than China’s and urges “a broad change in the irresponsible lifestyle connected with the Western model.” This would be to make progress in showing “genuine care for one another.” The pope neglects to mention that China is the world’s biggest carbon emitter and builds two coal plants a week.

When the 2018 agreement was signed, anonymous Vatican sources cast it as a “historic breakthrough,” an assessment repeated in headlines around the world. Xi’s repressive campaign of “Sinicizing” religion, which began earlier that year, before the agreement was signed, did not lead Rome to change its mind. The Vatican felt it could live with Sinicization requirements forcing clergy to “spread CCP principles,” “implement CCP values,” preach Xi’s thought, bar minors from attending church, allow surveillance of churches, and generally conform to party ideology. The Jesuit magazine America reported that Pope Francis was “convinced that even in the present difficult situation of a crackdown on religion in China, more is to be gained through dialogue, encounter and friendship.”

As a precondition of the deal, Francis recognized seven formerly “illegitimate” bishops appointed by Beijing, lifted the excommunication of three of them, and assigned one to replace a papally appointed bishop. The Vatican gave assurances that the seven had requested “reconciliation” with the pope.

The text of the 2018 agreement has been kept secret, but America published a summary from an “informed” source, just before it was signed. The terms allowed the Communist Party and the Council of Bishops it oversees to select bishop candidates after a “democratic election” system devised in 1957, “whereby the priests of the diocese, together with representatives of women religious and laypeople, vote from among the candidates presented by the authorities that supervise church affairs.” The pope was to be given a veto. The Vatican reportedly thought that China understood “that both sides share much in common on global issues and can work together toward peace and stability in the world.” But this hope was wishful thinking. Two years later, Beijing published regulations on appointing bishops that omitted any papal role. The last appointment approved by both sides was on September 8, 2021. Since then, the pope has been denied even a veto. Some 30 percent of China’s dioceses still lack bishops. Only a handful of episcopal appointments have been made since 2018, half without papal involvement. One bishop was transferred behind Francis’s back to a diocese created by the CCP, about which the Vatican issued a note of “regret.” For the sake of “unity and communion,” Francis approved the Chinese government’s unilateral appointment in April of Bishop Shen Bin to Shanghai. Shen also heads the Council of Bishops.

Benedict’s letter gives instruction to bishops recognized by the pope after joining the Patriotic Association: They “must increasingly give ‘unequivocal signs of full communion with the Successor of Peter.’” Bishop Shen, ordained with papal and government recognition, does not agree. In an interview last August, using terminology paralleling that from October’s Synod on Synodality, he said, “We cannot always stick to the old rules, think rigidly, be stuck in our ways, and live in the security of our own fantasies.” He also insisted on independence from papal authority:

We must . . . adhere to the principle of independence and autonomy in running the Church, adhere to the principle of democracy in running the Church, and adhere to the direction of the Sinicization of the Catholic Church in China. This is the bottom line, which no one can break, and it is also a high-pressure line, which no one should touch.

This view should not be surprising, however, since the Holy See yielded to the demand that China’s bishops join the Patriotic Association. Created under Mao for “reeducation” and oversight, in 2018 the Patriotic Association was brought under the direct authority of the Chinese Communist Party’s United Front Work Department, a propaganda arm that Xi has called one of his “magic weapons.” The association enforces a mandatory pledge of “independence” from foreign influence, which contravenes one of Benedict’s principles (“Communion and unity . . . are essential and integral elements of the Catholic Church: therefore the proposal for a Church that is ‘independent’ of the Holy See, in the religious sphere, is incompatible with Catholic doctrine”). Benedict also approved the underground church that formed after China’s Communist takeover and stated that “pastors and faithful have recourse,” if they feel constrained, to “the clandestine condition though it is not normal.” The agreement itself did not address the Patriotic Association issue. In 2019 pastoral guidelines, the Holy See, for the first time, permitted clergy to join the association. The guidelines theorized, preposterously, that the pledge’s reference to “independence” applied only in the political sphere because China’s constitution protects religious freedom.

The Patriotic Association doubtless includes faithful Chinese clerics. And it certainly includes CCP infiltrators. Chinese Communist espionage in the West is notorious and has not spared the church. In the 1970s, the FBI uncovered a spy in the Church of the Transfiguration in New York’s Chinatown. He posed as a Catholic priest but was actually a married Chinese-state-security agent and had trained over several years for the mission by saying Mass and hearing confessions in churches throughout Asia. Just as Ostpolitik was exploited by the KGB to send Eastern European clerics as spies to the Holy See and Vatican II, the current policy of Sinicization will provide further opportunities for CCP infiltration of the church. In 2020, China’s state-sponsored hackers targeted Vatican computer networks, according to Catholic News Agency.

Since the agreement, the CCP has rounded up for detention or banishment, by my count, six Catholic bishops who refuse to pledge their independence from the Vatican. Bishop Su and eleven others, arrested before the agreement, have continued to suffer persecution. At a 2020 press conference, Parolin admonished a questioner not to talk of “persecution” of China’s church, saying there were only “regulations that are imposed and which concern all religions, and certainly also concern the Catholic Church.” When pressed about Beijing’s repressive Sinicization policy, he incorrectly conflated it with “inculturation,” the benign practice, favored by 16th-century missionary Father Matteo Ricci, of adopting local dress and manners, as if this settled the question of ceding papal authority.

The Holy See does not acknowledge that China is breaking the agreement. It claims the deal is “working well,” if slowly, and that it was a “remarkable step forward.” Parolin praises it for “unifying” the church and creating conditions in which “both sides recognize the pope as the supreme leader of the bishops.”

With the agreement in shreds, the Vatican still makes various proposals to enhance dialogue, all based on a mischaracterization of the regime and its goals. Requests for a papal visit to China or a meeting elsewhere between Francis and Xi have gone nowhere. Xi even snubbed Francis during a Rome visit shortly after the agreement was signed, and he rebuffed a papal request to meet last year when both were in Astana, Kazakhstan.

The Vatican is now promoting Hong Kong’s newly minted cardinal Stephen Chow as a “bridge” to Beijing. Last April, Vatican public relations declared that then-bishop Chow’s receipt of an “invitation” to Beijing was another “historic” breakthrough. “A Jesuit like Matteo Ricci,” Chow would be “the first bishop of Hong Kong to make an official visit to the Archdiocese of Beijing since the former British colony was returned to China in 1997,” the Catholic press dutifully reported. In reality, Chow could not well refuse, since the invitation came from the party’s Patriotic Association chair, Li Shan, who also serves as Beijing’s bishop. Additional meetings were set up for Chow with Bishop Shen of the Council of Bishops and with the government religious office. Chow left Beijing saying that Xi “respects” the pope. Probably he was told to say this since, bizarrely, he also said that Xi’s “Community of Common Destiny” — the CCP’s global model embodied in his Belt and Road Initiative — “coincides” with Pope Francis’s “love for humanity.”

Chow also learned from Li that the Hong Kong church would have further visits with the mainland’s “official” church “to see how we can have more collaboration, in the formation of clergy.” The first group of Hong Kong priests quietly visited Patriotic Association priests in Beijing in September, and other priests and religious sisters are slated to go next. These visits are a tightened screw in the CCP’s consolidation of control over Hong Kong’s civil society.

China’s Catholic Church has grown to 12 million. In 2007, Benedict said that “during the last fifty years, the Church in China has never lacked an abundant flowering of vocations to the priesthood and to consecrated life” and “has seen a large number of adults coming to the faith.” Since then, the ground has shifted. Shen, of the Bishops Council, asserts that a drop in priestly vocations is being “felt significantly in China.” The church will struggle to survive as clergy are encouraged by the Vatican and pressured by the CCP to leave the underground for party-controlled churches that foster mutual suspicion and, instead of Christian truths, preach “Xi Thought.” Few among today’s younger Chinese, forbidden any exposure to religion as part of the repressive Sinicization program, can be expected even to consider the priesthood.

Benedict’s principles cite Pope John Paul II, who referred to Father Ricci’s own letters from Beijing and commented: “So too today the Catholic Church seeks no privilege from China and its leaders, but solely the resumption of dialogue, in order to build a relationship based upon mutual respect and deeper understanding.” But 40 years of flawed Vatican diplomacy in seeking dialogue has culminated in a 2018 agreement that gave CCP hard-liners permission to co-opt and undermine the Catholic Church in China. Unfounded assurances from papal functionaries that the regime respects the pope and shares his global-climate ambitions cannot hide this fact. The more the Vatican cedes its moral and spiritual authority, the more China’s church will be turned into a party asset, the more uninterested in actual dialogue the CCP will grow, and the less free China’s Catholics will be.