This summer’s bad news—floods in Louisiana, the spread of the Zika virus, police shootings, the threat of domestic terrorism—reminds us of a central challenge for any president: what to do when disaster strikes. Rush to the site and roll up his (or her) sleeves? Trust state and local leaders to handle the mess? Pick up the putter and finish that round of golf?

Modern presidents—with enormous federal capacities at their disposal and a media spotlight on the White House—are under great pressure to rise to the occasion. But it hasn’t always been this way.

In 1889, President Benjamin Harrison responded to the Johnstown flood in Pennsylvania, which killed more than 2,000 people, by sending a personal donation to the victims. His decision followed the bipartisan consensus of the time that presidents shouldn’t be involved in local crisis response. Principles of limited government were also at stake. In 1887, President Grover Cleveland vetoed relief funds for drought-stricken counties of Texas on the grounds that he could “find no warrant for such an appropriation in the Constitution.”

But such constraints didn’t last. In response to the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, President Calvin Coolidge sent his commerce secretary, Herbert Hoover—who had won praise for orchestrating food distribution in Europe after World War I—to run relief efforts. Before this intervention, Coolidge was criticized for dallying: Will Rogers quipped that he was stalling in the “hope that those needing relief will perhaps have conveniently died in the meantime.”

During Hurricane Camille in 1969, President Richard Nixon sent his vice president, Spiro Agnew, to the Gulf Coast. Noting the limitations of forecasters in predicting dangerous weather, Nixon later ordered federal officials to improve their forecasting capabilities—which led the National Hurricane Center to develop the five-category hurricane-wind scale familiar to us today.

Today, once a crisis dominates headlines, cable news and social media, presidents don’t really have the option of standing aside. They must make practical and political calculations about whether and how to get involved, as President Barack Obama did this week in deciding to visit flood-ravaged Louisiana after initially remaining on vacation on Martha’s Vineyard.

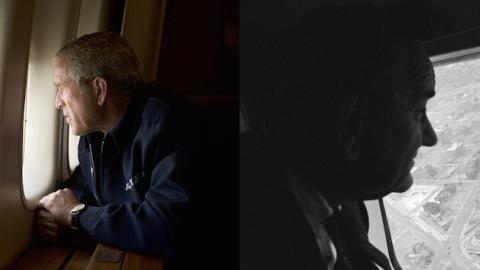

Presidential visits aren’t always the right answer: They gobble up local personnel and resources that are often needed urgently elsewhere. But a mere “flyover” is no substitute, as President George W. Bush learned in 2005 when he did an aerial survey of a drowning New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina. It made him look detached, wary of involvement, and it confirmed impressions made by his administration’s slow, botched early response to the disaster.

But he wasn’t the first to make this mistake. In 1968, during the unrest following the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., President Lyndon Johnson rode in a helicopter over riot-torn areas of Washington, D.C. A photo taken at the time of LBJ looking down on the devastation is a perfect image of presidential remoteness.

In 1979, President Jimmy Carter created the Federal Emergency Management Agency, but catastrophes today require more than behind-the-scenes presidential deployment of FEMA and other assets. They demand a show of compassion. No president can afford to be seen as callous about widespread loss of life. In 1918, Woodrow Wilson did and said little as 675,000 Americans died in the Great Influenza; no modern president could get away with that. Franklin Roosevelt offered a better approach for dealing with crises during the Great Depression—not just marshaling federal resources but also using his mastery of the new medium of radio to reassure the American public.

Still, the most effective approach to disasters is to prevent them. Here, presidents can look to the model of President Bill Clinton, who faced the Y2K crisis, which threatened an epic crash of computer systems unprepared to change from 1999 to 2000. Mr. Clinton brought together government agencies at multiple levels with the private sector to ensure that the country’s computer systems were ready.

We cannot know in retrospect how severe the damage might have been, but avoiding a crisis is always better than responding to one. Whoever is inaugurated in January 2017 should keep that in mind.