Executive Summary

This paper begins by explaining the importance of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan to the Sino-Russian relationship. The next section analyzes Russian and Chinese goals regarding these two states and other Central Asian countries. These two major powers have security objectives that are sometimes similar and rarely confrontational. Their economic goals more often diverge, but Moscow and Beijing still collaborate more than they conflict, and several recent joint initiatives have achieved substantial mutual gains. The final section analyzes the evolution of the Sino-Russian partnership concerning Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, the limited role of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) in sustaining their collaboration, the main drivers of their cooperation, future potential scenarios, and the implications for the United States.

Hudson Institute has produced this paper for the study Russia-China Security Interactions in Central Asia: Bilateral and Multilateral Dimensions. This project analyzes the Sino-Russian relationship in Central Asia through three case studies. The first two papers assess Russian and Chinese ties with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, which have the largest militaries, economies, and populations in the region. The third paper evaluates Sino-Russian interactions with the SCO. This final paper draws on these three texts and other data to assess Russia’s and China’s overall relationships in Central Asia, project their future interactions in various scenarios, and evaluate the implications for the United States and its partners. Senior Fellow Richard Weitz is the primary author of this paper. Alexander Peris and Marie Mach provided research assistance. David Altman, Mark Melton, Hannah Skaggs, and Konstantin Shchelkunov helped edit the text, while Ian Maready helped with the design. Hudson Institute would like to thank the Russia Strategic Initiative of the US European Command for funding this study.

Takeaways

- Central Asia has been a bellwether of the Sino-Russian relationship.

- Russia accounts for almost all of Kazakhstan’s imported weapons systems, while Uzbekistan buys most of its imported arms from Russia.

- China has pursued a less assertive stance toward potential territorial conflicts in Central Asia than in other regions.

- Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have constrained their security cooperation with Russia, but their economic ties with Russia and China have strengthened substantially.

- The transformation of Eurasian energy markets promotes Sino-Russian cooperation and provides Moscow and Beijing with additional leverage over Central Asia.

- Western sanctions have spurred Chinese, Kazakhstani, and Uzbekistani efforts to construct alternative transportation routes and pursue foreign markets outside Russian territory.

- A peace deal with Ukraine could allow Russia to devote more security resources to Central Asia while reducing Kazakhstan’s and Uzbekistan’s importance to sanctions circumvention.

This publication was funded by the Russia Strategic Initiative, U.S. European Command. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Defense or the United States Government.

Introduction

Central Asia has been a bellwether of the Sino-Russian relationship. Against some expectations, the region did not become an arena of rivalry between a rising People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the new Russian Federation, whose predecessor had tightly controlled the Central Asian republics from Moscow. Instead, Russia and China rapidly established and consistently sustained a cooperative framework in Central Asia to pursue their common, or at least non-conflicting, regional goals. This collaboration may partly explain the relatively low level of interstate violence the region has experienced since 1990 despite the border disputes and many transnational challenges facing Central Asian states. Among these troubles are terrorism and religious extremism, narcotics and human trafficking, underdeveloped infrastructure, and, until recently, leaders who often cooperated better with extra-regional governments than with neighboring regimes.1

|

Paper Roadmap

|

Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are important for both Central Asia and the Sino-Russian relationship. Thanks to the vast revenue from its sizeable oil and gas exports, Kazakhstan has the largest economy and defense budget among the five Central Asian countries (see table 1). Kazakhstan is a formal military ally of the Russian Federation and the second-largest contributor to the Moscow-led regional alliance, the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO).

Table 1. Central Asian Countries Ranked by GDP (Nominal, 2023)

|

1 |

Kazakhstan |

$262.64 billion |

|

2 |

Uzbekistan |

$101.59 billion |

|

3 |

Turkmenistan |

$60.63 billion |

|

4 |

Kyrgyzstan |

$13.99 billion |

|

5 |

Tajikistan |

$12.06 billion |

|

Source: “GDP by Country,” Worldometer, accessed May 21, 2025, https://www.worldometers.info/gdp/gdp-by-country/. |

||

Table 2. Central Asian Countries Ranked by Population (2025)

|

1 |

Uzbekistan |

36.36 million |

|

2 |

Kazakhstan |

20.59 million |

|

3 |

Tajikistan |

10.59 million |

|

4 |

Turkmenistan |

7.49 million |

|

5 |

Kyrgyzstan |

7.19 million |

|

Source: “Central Asia Population,” Worldometer, accessed May 21, 2025, https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/central-asia-population/. |

||

Yet ethnic ties continue to complicate Russian-Kazakhstani relations. In recent years, prominent Russian figures have called on Moscow to take stronger measures to defend ethnic Russians and Moscow’s interests in Kazakhstan. Despite the Moscow-led CSTO intervention in January 2022 in support of the current government, Kazakhstan has not provided military support to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. Kazakhstan’s multi-vector foreign policy is also evident in the economic realm and in its support for Central Asian solidarity and cooperation. Nonetheless, though China has surpassed Russia as Kazakhstan’s leading economic partner, Russia will remain its most significant military ally for the foreseeable future.

Uzbekistan is important to Central Asian stability. It has the largest population of the five Central Asian countries (see table 2). Furthermore, many ethnic Uzbeks reside in neighboring countries, providing pathways for internal instability to spill across national boundaries. Additionally, Uzbekistan is the only Central Asian country bordering the other four Central Asian states, giving Tashkent a pivotal position in regional integration efforts.

During the past decade, Uzbekistani diplomacy has transformed from routinely resisting such cooperation to regularly backing it, often in collaboration with Kazakhstan. In contrast with the other Central Asian countries, moreover, Uzbekistan does not adjoin Russia or China, which gives Tashkent geopolitical maneuvering room. Uzbekistan has maintained good relations with China while moving closer to Russia since Shavkat Mirziyoyev became president in 2016. During that time, Russia and Uzbekistan have resumed large-scale bilateral military exercises and defense-industrial cooperation.

Moscow wants Uzbekistan to integrate with Moscow-led regional institutions, deepen defense connections through expanded arms sales and military exercises, and assist Russian economic and energy aspirations throughout Eurasia. Though Uzbekistan has strengthened ties with Russia in recent years, it has declined to rejoin the CSTO’s military structure, which it left in 2012.

Russian and Chinese Goals

Maintaining influence in Central Asia remains a critical national interest for the Russian government. The region has arguably become more important to the Kremlin in recent years due to the deterioration of Russia’s relations with so many other countries following its aggression toward Ukraine. Meanwhile, Central Asia is significant to the PRC as a potential source of transnational threats, energy security, and economic interactions with the rest of Eurasia. Given their large size, pivotal location, and other characteristics, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have been priority countries for achieving Moscow’s and Beijing’s policies in the region.

Russian Objectives

|

Moscow’s Priorities Concerning Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan

|

Moscow wants Central Asian governments to integrate with its regional institutions, deepen defense ties through expanded arms sales and military exercises, and support its economic and energy aspirations throughout Eurasia. Russian authorities strive to prevent terrorists, drug traffickers, and illegal migrants from entering their territory. Strengthening border security with Kazakhstan, the largest country in Central Asia, has been a Russian priority. The two countries share the longest continuous national land border in the world along northern Kazakhstan, but Russian strategists also see Kazakhstan as a buffer against external threats originating farther south, including from Afghanistan. Foreign fighters from Central Asia and Afghanistan have supported separatism and terrorism in the North Caucasus and participated in last year’s deadly attack on the Crocus City Hall music venue in Moscow Oblast.

The Russian government strives to intensify multilateral ties with Central Asian countries. For example, Moscow presses Uzbekistan to elevate its engagement with the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and the CSTO. Uzbekistan holds observer status in these Moscow-led regional organizations, but Russia hopes it will eventually become a full member in the EAEU and rejoin the CSTO. Russia also strives to increase weapons sales and exercises with Uzbekistan’s armed forces. Though Kazakhstan is a reliable member of the EAEU and the CSTO, Astana has not accepted Moscow’s invitation to join the BRICS Plus bloc (which includes Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa).

Conversely, Moscow wants Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan to limit their security ties with Western countries. The Russian government routinely promotes non-Western multinational structures, such as the SCO, as tools to disrupt the established international order and advance its own regional diplomatic, economic, and security goals. Participating in the SCO elevates Russia’s diplomatic status, helps Moscow pursue economic integration in Asia, and supports its advocacy for a Eurasian security system independent of the West. Russian diplomacy advocates this restructuring in both the security and economic domains. According to Vladimir Putin, the core components of the new Eurasian security system could include a partnership among the Union State of Belarus and Russia, the CSTO, the Commonwealth of Independent States, and the SCO.2

Russia’s longstanding economic objectives regarding Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan include maintaining strong trade, energy, investment, transportation, and business ties and supporting Moscow-led regional economic structures. Russian leaders envisage a Greater Eurasian Partnership that aggregates the EAEU, the SCO, and other Eurasian regional associations, along with Russian and Chinese regional integration projects. A new and growing Russian priority is securing Kazakhstani and Uzbekistani participation in re-exporting and other schemes to circumvent Western sanctions. They have also encouraged Russia’s partners to use non-Western financial instruments that are less vulnerable to international sanctions.

Chinese Objectives

|

China’s Priorities Concerning Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan

|

Following the Soviet Union’s collapse, the PRC focused on preventing ethnic Uyghurs and other Muslims in Uzbekistan and particularly Kazakhstan from challenging its control over the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. More generally, it has sought to work with Kazakhstani and Uzbekistani authorities to limit transnational terrorism, political instability, and other potential threats. Economic objectives have become more significant as Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have emerged as major sources of China’s growing energy imports. Like their Russian counterparts, PRC policymakers perceive Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan as conduits connecting China with the South Caucasus, the Middle East, and Europe.

The PRC initially prioritized neutralizing potential threats from Central Asia to its control over the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. For years, the PRC has repressed Xinjiang’s previously dominant Muslim ethnic Uyghur population, which shares cultural, linguistic, and other ties with the populations of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. All the PRC’s land-based commercial transit with Central Asia traverses Xinjiang.

Beyond Xinjiang, an uptick in terrorism and instability in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan could pose serious threats to Beijing’s New Silk Road vision for Central Asia as well as its trade and investment assets in those countries. Such instability near China’s western frontiers (i.e., its strategic rear) would also divert PRC attention and resources away from confronting the United States and its allies and partners in other parts of Asia. These concerns became more pressing after the Taliban’s 2021 return to power and the resurgence of Islamic State–Khorasan in Afghanistan. That terrorist group has conducted large-scale attacks inside Russia and Iran and has launched rockets into Uzbekistani territory.3

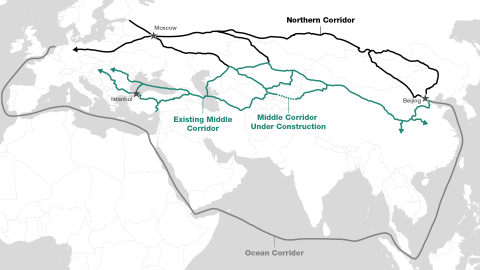

The PRC’s economic goals concerning Central Asia have become more important as the region has contributed more to China’s energy security and foreign trade. Chinese investment helped construct the pipelines and other infrastructure that enable the PRC to import oil and natural gas from Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. These overland energy shipments obviate the need for Beijing to rely on vulnerable sea lanes susceptible to disruption by pirates or foreign navies. The PRC wants the Kazakhstani and Uzbekistani governments to protect Chinese economic investments and nationals in their countries. For example, Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) finances infrastructure development in other countries to envelop them within PRC economic networks. The PRC aspires to use the BRI and other transportation initiatives to exploit Kazakhstan’s and Uzbekistan’s pivotal locations between China, Europe, South Asia, and the Middle East (see map 1).

Map 1. Primary Railway and Sea Routes between China and Europe

Source: Adapted from “To Secure Exports to Europe, China Reconfigures Its Rail Links,” The Economist, April 6, 2025, https://www.economist.com/china/2025/04/06/to-secure-exports-to-europe-china-reconfigures-its-rail-links.

China also wants Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan to support its other economic, security, and ideological foreign policy initiatives. These have waxed and waned over the years but have included, most prominently, the BRI and, more recently, the Global Development Initiative, Global Security Initiative, and Global Civilization Initiative. Beijing tries to wield these initiatives in an integrated manner to further its international economic, security, and other objectives. China also expects full backing for its positions regarding Taiwan, Tibet, and other issues of critical concern to its leaders.

Russian Means

Russia has combined bilateral agreements involving Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan with multinational initiatives channeled through Moscow-led regional organizations, such as the CSTO and the EAEU, to project influence in Central Asia.

|

Moscow’s Tactics Regarding Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan

|

Security Sinews

Russia remains the leading defense partner of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. They conduct frequent military exercises and cooperate extensively on defense-industrial development. Russia is the source of almost all of Kazakhstan’s imported weapons systems and most of Uzbekistan’s foreign arms. Central Asian governments have sought to manufacture more weapons systems and diversify arms suppliers beyond Russia’s heavily sanctioned military-industrial complex, which prioritizes Moscow’s war needs. However, Russia’s policy of subsidizing arms sales is enticing to countries like Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan given their modest defense budgets.

The Moscow-dominated CSTO is Central Asia’s most important regional security institution. Russia employs the organization to support its regional security operations, justify its military presence in Central Asia, and constrain members’ defense cooperation with Western countries. In return, other members can purchase Russia-made weapons at a discount, participate in the Russian professional military education network, and exercise with Russia’s experienced combat forces. Kazakhstan is the most significant CSTO member after Russia, assigning many elite units to the organization and regularly participating in its missions. In January 2022, a Russia-dominated CSTO force intervened to support Kazakhstan’s government against mass riots. Though Uzbekistan did not object to the military intervention, it has resisted Moscow’s pressure to become a full CSTO member to preclude the organization’s interference in its internal affairs in a crisis.

Despite the Soviet Union’s breakup and Central Asians’ diversifying security ties, the connections between Russian and Central Asian intelligence, law enforcement, and internal security entities have always been strong. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan do not face conventional military threats from other nation-states (excluding potential Russian military aggression). However, transnational security challenges—such as Islamic militarism, narcotics trafficking, and natural and human-made disasters—present perennial risks. The Russian and Central Asian security services regularly collaborate against terrorism, extremism, cybercrime, illegal migration, drug trafficking, and other transnational challenges. Their security establishments share doctrines, weapons, and training. Uzbekistani authorities cooperated with the Russian intelligence and law enforcement agents investigating the Uzbekistani nationals implicated in the March 2024 attack on Moscow’s Crocus City Hall. They also assisted the investigation of alleged Uzbekistani involvement in the subsequent killing of General Igor Kirillov, chief of Russia’s Nuclear, Biological and Chemical Protection Troops, in Moscow.

The governments of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have formally adopted neutral positions regarding the Russia-Ukraine War and barred their citizens from joining the fight. Their governments have urged an end to the conflict and have declined to recognize Moscow’s annexation of Ukraine’s internationally recognized territory. The Russian government has not openly challenged Kazakhstan’s and Uzbekistan’s positions on the war.

However, some Russian media commentators and public figures associated with the Kremlin have voiced their irritation and proposed potential retaliation. Entities in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have provided dual-use assistance to Russia’s war machine, which may have mollified Moscow’s anger. Many defense-related goods from China also enter Russia via Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. For example, Kazakhstan re-exported to Russia approximately half of the $5.9 million worth of drones it imported from China in 2023.4 The Russian invasion of Ukraine depreciated Uzbekistani interest in moving closer to Moscow by rejoining the CSTO or becoming a full member of the EAEU. However, Russian-owned factories in Uzbekistan produce cellulose-based ingredients that Russian defense factories use to manufacture explosives and propellants.5

Economic and Energy Connections

The Russian Federation has remained an important economic partner of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, though its share of their trade has fallen below that of China. Russia is a leading source of foreign direct investment in each country. Major Russian state corporations like Rosatom, Gazprombank, VEB, Gazprom, and Lukoil operate in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan in such sectors as aerospace, automotive, chemicals, energy, metallurgy, mining, pharmaceuticals, telecommunications, and textiles.

For many years, oil and gas exports from Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan depended heavily on access to Russia-controlled pipelines that flowed northward to central Russia before branching off to European markets. Despite construction of alternative routes, more than 80 percent of Kazakhstan’s oil exports still traverse Russian territory. Kazakhstan also imports electricity from Russia, and the two countries cooperate extensively in the nuclear power sector.

The millions of Central Asian nationals who pursue temporary employment in Russia provide Moscow with another source of influence. Russian employers need migrant workers from Uzbekistan and other Central Asian states to alleviate labor shortages. The Russian government therefore offers them visa-free entry and other inducements. Yet the Russian authorities can curtail these inducements and migrants’ movement, employment, or remittances to exert leverage on their home countries.

Russia has encouraged Central Asian governments to use more non-Western financial instruments, which are less vulnerable to international sanctions. Despite Western sanctions, the Russian ruble remains an essential business currency in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan since their national currencies are not internationally convertible. More than half of the two-way transactions involving entities in Russia and those in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are settled in their national currencies. However, more extensive use of non-Western financial instruments is almost exclusively bilateral, between Russia and another country, rather than through multinational cooperation. Russian proposals to establish a payment and settlement system within the SCO have failed.6

Soft Power and Influence Assets

In Central Asia, knowledge of the Russian language is extensive due to the legacy of the Soviet era, the large number of ethnic Russians, and the teaching of basic Russian in many schools. Ethnic Russians comprise approximately one-sixth of Kazakhstan’s population. Russian TV broadcasts, newspapers, magazines, and websites are widely accessible. Tens of thousands of students from Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan study at Russian universities, either within Russia or at universities and joint educational institutions operating in Central Asian countries. The Russian government subsidizes some of these programs, while Russia-supported nongovernmental organizations promote the Russian language and official Russian values in Central Asia.

In Kazakhstan, authorities have encouraged wider use of Kazakh, but Russian remains an official language for government business. Even though President Kassym-Jomart Kemeluly Tokayev has orchestrated the Kazakh language’s transition from Cyrillic to Latin script, he has stressed his support for continuing Russian education and language use in Kazakhstan. Tokayev proposed establishing an International Organization for the Russian Language, which Kazakhstan, Russia, Uzbekistan, and other former Soviet republics formally launched in 2023.7 It promotes the Russian language for international communication and for advancing historical and scientific knowledge and literature. Public opinion polls find that Central Asian respondents generally rate the Russian Federation and President Putin favorably.8

Chinese Means

During the past 35 years, the PRC has forged strong diplomatic ties with Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and other Central Asian countries. China defines its relationship with Kazakhstan as a “permanent comprehensive strategic partnership,” and with Uzbekistan as “an all-weather comprehensive strategic partnership for a new era.”9

Interestingly, China has taken a less assertive stance toward potential territorial conflicts in Central Asia than in East Asia. Instead of exploiting the collapse of Soviet military power to press its suppressed territorial claims and other ambitions, PRC diplomats have shown atypical restraint regarding Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. Yet Chinese officials do successfully insist that their Central Asian counterparts back their view of sensitive issues, such as Taiwan (embracing “the one-China principle”), Xinjiang (pledging to fight the “three evil forces” of terrorism, extremism, and separatism), and international order (praising Xi Jinping’s Global Security Initiative, Global Civilization Initiative, and Global Development Initiative).10

|

Beijing’s Tactics Regarding Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan

|

Through the SCO, the PRC can pursue its intertwined diplomatic, economic, and security objectives in Central Asia within a cooperative multilateral structure that does not disrupt these other regional initiatives. Beijing has been the driving force behind the SCO’s evolution outside the security realm. PRC discourse emphasizes the congruence of Chinese-SCO values and takes pride in how the so-called Shanghai Spirit animates the organization.11

More concretely, China has found the SCO a valuable instrument for advancing its priority programs and challenging Western influence in Central Asia. It does so without overtly threatening Russian interests by characterizing its activities as SCO rather than PRC projects. China can advance its objectives directly through SCO-related measures and indirectly by leveraging SCO diplomatic and economic ties. It induces other governments to pursue its preferred policies, such as suppressing anti-PRC messaging and embracing Beijing-backed economic initiatives.

Security Ties

Beijing has been slowly enlarging its security profile in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan due to its growing economic interests, concerns about regional terrorist movements, and generally more assertive foreign policy orientation. Initially, major obstacles inhibited more traditional defense cooperation between China and these Central Asian countries. These barriers included their different military traditions, the absence of Chinese bases in Central Asia, local concerns about Beijing’s long-term ambitions in the region, and PRC deference to Moscow’s security primacy in Central Asia. Language barriers have also impeded Chinese exchanges with Kazakhstani and Uzbekistani military leaders.

Over time, though, China’s security presence in Central Asia, including Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, has grown. This enlargement reflects Beijing’s expanding stakes in the region as well as the overall increase in PRC foreign policy activism and security capabilities. Protection of Chinese citizens abroad has become a more prominent foreign policy objective. As China has increased its economic projects in Central Asia, more PRC nationals have been working there, raising Beijing’s concern about their safety.

The Chinese, Kazakhstani, and Uzbekistani governments routinely share intelligence about terrorist threats. The PRC also offers education and training opportunities to Kazakhstani and national security personnel. China’s and Kazakhstan’s regular armed forces participate in various bilateral and multilateral exercises. In addition, their law enforcement agencies and paramilitary forces—in China’s case, the Ministry of Public Security and the Chinese People’s Armed Police—also frequently engage in joint drills.12 The PRC conducts special operations, counternarcotics, and counterterrorism exercises with Uzbekistan as well.

Though the PRC has substantially increased its overall military budget in recent years, relatively few funds have gone toward reinforcing China’s frontier forces bordering Central Asia. But one previous barrier to a much more significant presence in the region has waned as the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has developed more effective power projection and logistical capabilities on its western frontier. At first, China provided only nonlethal military equipment to Kazakhstan, such as uniforms, jeeps and other vehicles, communications systems, and information technologies. But recently, the PRC has given Kazakhstan more dual-use equipment—items with both military and commercial applications—such as drones and microelectronics.13 China has occasionally also sold weapons to Uzbekistan. Recent open-source reports indicate that Uzbekistan may purchase advanced fighter planes from the PRC.14

Economic and Energy Developments

During the past two decades, China has forged strong economic links with Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and other Central Asian countries. Their governments have generally welcomed the opportunity to diversify their commercial ties and finance major telecommunications, transportation, and other development projects. PRC investment in Central Asia has grown rapidly since 1991. Its entities possess considerable capital and substantial experience in constructing massive infrastructure projects.

Large loans, with more flexible terms and fewer conditions than US financing requires, have supported the construction of east-west transportation networks, including energy pipelines through Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan that have enabled growing Chinese–Central Asian economic ties. Not only do Central Asian countries have significant oil and natural gas deposits, but their proximity to western China also obviates the need for less secure maritime deliveries.

Although trade with Central Asia represents a small proportion of China’s overall foreign commerce, PRC officials have been eager to enhance economic ties between Central Asia and their country’s relatively impoverished northwestern regions. One example is Xinjiang, whose development has lagged behind China’s vibrant eastern cities. Despite international concerns about forced labor in Xinjiang, the PRC recently launched a new cargo train on its China-Europe international freight railway that can deliver small e-commerce consumer items produced in Xinjiang to postal services throughout Europe.15

Even so, the PRC has had less success in removing non-physical barriers to trade and investment in Central Asia. These include unhelpful visa and customs policies; inadequate financial and communications networks; terrorism, extremism, narcotics trafficking, and other border security threats; and insecure property rights and rule of law, which discourage foreign investment.

Xi launched the BRI during a 2013 speech in Kazakhstan, underscoring the country’s importance to the initiative and to the Chinese economy. PRC-Kazakhstani trade exceeded $40 billion in 2023.16 Kazakhstan accounts for almost half of the PRC’s trade with the five Central Asian countries, while more than one-fifth of Kazakhstan’s foreign trade is with China.17 The PRC has also displaced Russia as Uzbekistan’s leading trade partner in terms of overall turnover and imports, though China ranks only as Uzbekistan’s second-highest export destination. Kazakhstan supplied China with 4.4 billion cubic meters of gas in 2022 and 5.8 billion in 2023.18

Through the BRI and related initiatives, the PRC has helped improve Kazakhstan’s and Uzbekistan’s transportation, energy, and other networks. The Kazakhstani and Uzbekistani governments have launched independent but complementary initiatives to enlarge and accelerate transit across their territories. Through their parallel infrastructure-building initiatives, China, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan have increased trade and investment flows and decreased trans-Eurasian transport times.19 PRC messaging depicts this interaction as a win-win partnership. China’s exports to Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and other Central Asian states have surged since 2022, which suggests it exports some goods to Russia through Central Asia when it cannot send them directly due to Western sanctions.

Soft Power and Influence Assets

While lacking Russia’s regional linguistic advantages, China has strived to envelop Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan within its influence network. The PRC maintains five Confucius Institutes in Kazakhstan and two in Uzbekistan. Thousands of Kazakhstani and Uzbekistani students study at Chinese universities, and Beijing subsidizes many of them.20 Mirroring Russia’s approach, China has expanded its local higher-education offerings as well. Presidents Tokayev and Xi jointly attended the opening of the Beijing University of Language and Culture in Astana in early 2024.21

The PLA has pursued educational and training exchanges with the two states’ service members. The Xiangshan Forum, an annual PLA defense and security conference that shares PRC perspectives on international security issues, regularly includes representatives from both countries. In 2014, Beijing established a training institute for the officers of SCO member states. Chinese professional military education (PME) institutions have educated senior military officials from Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan.22 Nonetheless, language, cultural, and other barriers to interaction between Chinese and international students continue to hinder PRC efforts to expand PME to Central Asian officers.23

As COVID-19 travel restrictions ended, reciprocal tourism between Central Asia and China rebounded. Kazakhstan and China have implemented a lenient visa regime for each other’s nationals and taken other measures to attract each other’s tourists, with moderate success.24 Uzbekistan has also worked to attract Chinese tourists, dubbing 2025 the “Year of Tourism” at an event in Beijing.25 Uzbekistan has already achieved some success in attracting PRC visitors: Chinese tourism to Uzbekistan increased by 75 percent in 2024.26 Chinese television broadcasts in both Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan are widely available if not manifestly popular. A larger number of Central Asians use PRC-origin apps and telecommunications systems. The PRC has launched a dedicated China–Central Asia mechanism with leadership summits and a permanent secretariat.27

Russia-China Interactions and Implications

|

Evolution of Sino-Russian Partnership Regarding Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan

|

Following the Soviet Union’s breakup, the Russian government initially attempted to erect barriers between the newly independent states of Central Asia and the Chinese economy. For instance, Russian authorities tried to prevent the Russia-Kazakhstan-Belarus Customs Union from serving as a backdoor for smuggling inexpensive PRC products into Russia by pressing Kazakhstani authorities to tighten border controls with China.28 According to subsequent calculations, the Moscow-led EAEU has increased Kazakhstan’s trade with Russia at the potential expense of nonmembers like China.29

Due to the legacy of the integrated Soviet economy, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan initially depended heavily on transportation, communications, supply chains, and other networks that either traverse Russian territory or fall under Russian control. Since then, the PRC has undertaken a sustained campaign to construct transportation and other infrastructure connecting China to these countries. Kazakhstani and Uzbekistani trade turnover with the PRC now exceeds that with Russia for the first time in centuries. To minimize Russian and Central Asian public concerns, PRC firms have traditionally maintained low public profiles in the region.

Russian leaders appreciate the long-term challenges of managing Chinese economic power in Central Asia. A presentation of Russia’s long-term economic strategy by Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin in April 2024 warned that the growing Chinese presence could undermine Russia’s long-term plans for Eurasian economic integration.30

Given Western sanctions and Russia’s other economic challenges, though, Russian policymakers have come to terms with China’s growing economic presence in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Their reasons include these countries’ proximity to the PRC, Beijing’s generally benign approach toward Russia, Moscow’s limited tools for hobbling China’s economic role in Central Asia, and the insatiable PRC demand for natural resources, which invariably augments China’s economic presence. Furthermore, influential Russians gain jobs, investments, and capital from PRC-related investments and trade. Russian entities have leveraged the developing transportation infrastructure to exchange more goods through the PRC via Kazakhstani and Uzbekistani territory.

Russian strategists also believe that China’s east-west integration efforts give Moscow leverage over Beijing because China needs to avert Russian impediments to China–Central Asian transit. Expectations that Western countries could limit their economic ties with Russia indefinitely have amplified Russian aspirations to expand exports throughout Asia. Meanwhile, Russian companies have secured long-term contracts to help China acquire energy from Central Asia.

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Kazakhstan’s and Uzbekistan’s economic ties with Russia and China have substantially increased, particularly in the energy and transportation domains. Western sanctions led Russian commercial entities to redirect trade away from Europe and toward Asian partners, especially in China and Central Asia. In addition, entrepreneurs in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have orchestrated a mutually beneficial partnership through which sanctioned goods from China and other sources enter Russian territory through Central Asia. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan achieve economic benefits from all these projects, but they have become more vulnerable to pressure from Moscow and Beijing.

For example, the transformation of Eurasian energy markets promotes Sino-Russian cooperation. Russian and Chinese entities now frequently partner on mutually beneficial commercial deals involving Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. In December 2024, Russia’s leading nuclear corporation, Rosatom, sold shares in several Russian-Kazakhstani uranium mining ventures to subsidiaries of major Chinese state-owned companies, perhaps presaging an expansion of trilateral cooperation in Kazakhstan’s growing nuclear energy sector.31 Uzbekistan is also seeking foreign partners to support its nuclear power ambitions. This situation provides Moscow and Beijing additional leverage over both countries. In November 2022, Putin abruptly called for a so-called gas union among Russia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan. The Central Asian countries can earn transit revenue and other commercial benefits from Sino-Russian economic cooperation, but it creates vulnerabilities that Moscow and Beijing can manipulate to advance other objectives, such as constraining Central Asians’ military relations with the West.

However, Western sanctions have spurred Kazakhstani, Uzbekistani, and Chinese interest in transportation routes that circumvent Russian territory. Though under discussion for decades, construction of the planned China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan (CKU) railway has gained renewed attention.32 The railway could help all three countries ship goods faster and cheaper between China, Europe, and the Middle East through Central Asia. In the past, China was reluctant to commit to the project since it would have to provide most of the funding. Moscow also opposed the CKU because it would compete with alternative Middle Corridor routes through Russian territory. However, Russian resistance has waned. Moscow’s stalemated invasion of Ukraine and Western sanctions have made Russian diplomacy more solicitous of Chinese and Central Asian concerns.

Many differences between Russia and China regarding Central Asia are procedural rather than substantive. For example, Beijing uses the SCO and other non-military institutions to legitimize its essentially bilateral and unilateral policies in Central Asia, while Moscow favors the CSTO, a collective defense pact that excludes China. Furthermore, Russia has an extensive military presence in Central Asia, including several long-term bases, whereas the PLA has sent troops there only for short-term exercises. Beijing has also historically limited its sales of advanced weaponry to the region to avoid irritating Moscow, though this may be changing.33 Whatever these differences, the Russian and Chinese governments share the perception that Central Asia should fall within their overlapping spheres of influence, to the exclusion of other actors, and that they should subordinate their specific differences concerning the region to their larger global strategic orientation and partnership.

The SCO

Russia and China’s dual leadership of the SCO embodies their overlapping interests in Central Asia. The PRC employed the organization to elevate its influence without alarming Moscow, whereas Russia valued how the organization helped monitor and channel that expansion. Though the organization lacks substantial authority or structure, its existence has provided Moscow and Beijing with a flexible multilateral framework to manage their sometimes-diverging policies in Central Asia. For example, China used the SCO to give bilateral political and economic agreements with Central Asian governments a nominally multilateral appearance.

Additionally, while China’s security role in Central Asia has grown substantially in recent years, it has more carefully encroached on Russia’s perceived military primacy in the region. The PRC has generally avoided large-scale defense drills with Central Asian states, instead focusing on smaller counterterrorism drills featuring paramilitary, police, and special forces. Channeling engagements through the SCO’s multilateral framework enables China to increase its security role in Central Asia without challenging Russia directly.

While acknowledging China’s security activities in Central Asia as unavoidable, Russian policymakers have worked to retain their leading roles in regional anti-terrorism structures. Moscow’s participation in the SCO has partly aimed to help Russia manage competition from China’s bilateral and multilateral initiatives, which challenge Russia-led regional blocs such as the CSTO and the EAEU. For instance, Moscow’s resistance has constrained Chinese proposals to reduce trade barriers among SCO members or provide the SCO with strong financial development institutions.

There have been visible Sino-Russian disagreements regarding how the SCO should develop. Moscow has professed support for various Chinese economic initiatives in principle. But in practice, it has exploited the organization’s unanimity rule to block PRC proposals to create an SCO-wide energy club, free trade zone, and robust development bank.34 Sino-Russian security differences have also circumscribed the SCO’s potential military role. For instance, the PRC blocked Russian efforts to strengthen ties between the SCO and the CSTO. More recently, some PRC scholars have proposed relaxing the unanimity requirement and allowing a simple majority of members to overcome some deadlocks and increase institutional efficiency. Russian representatives have resolutely opposed waiving the rule.35

The SCO’s role is in flux due to its membership expansion, resistance to Moscow’s attempts to use the organization against the West, and China’s potentially competing security initiatives. Even so, Moscow and Beijing have cooperated to sustain the organization’s counterterrorism and other non-military security roles. Fundamentally, Moscow and Beijing still benefit from the SCO as a form of mutual reassurance, in which they overtly acknowledge one another’s interests concerning Central Asia.During the last few years, the Russian and Chinese governments have collaborated to enlarge the SCO’s agenda and, more recently, membership beyond Eurasia. They showcase the SCO as a concrete manifestation of non-Western approaches to international issues.36 More concretely, they can leverage other countries’ interest in joining the SCO to their advantage.

|

Drivers of Sino-Russian Cooperation in Central Asia

|

Future Scenarios

Central Asia has always been a geographic focus of Sino-Russian attention. Russian and Chinese priorities regarding Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are generally harmonious. Both seek border security, commercial opportunities, regional stability, friendly regimes, and partners for countering extremism, terrorism, and separatism. Were Sino-Russian fissures to emerge, Moscow and Beijing would likely manage their divergences successfully and, as in other cases of potential but averted conflict, keep these differences from damaging their overall partnership.

Several factors have furthered Sino-Russian collaboration in the past and will likely do so in the future. These include tolerance of each other’s activities; shared concerns about international terrorism, drug trafficking, and other transnational threats; determination to avert social revolutions and mass disorders in Central Asia, such as during leadership succession scenarios; mutually beneficial cooperative economic projects; and the goal of constraining local elites from aligning with the United States and other extra-regional partners. Moscow does not challenge China’s demand that Central Asian governments support Beijing’s position regarding Taiwan, Tibet, and Xinjiang. Furthermore, Russian leaders have not insisted that the governments of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan (or China) officially support Moscow’s territorial claims vis-à-vis Ukraine or Georgia.

Despite its contributions to Russian and Chinese goals for Central Asia, the SCO is not critical to this Sino-Russian partnership. Many accords that countries have adopted under SCO auspices consist primarily of bilateral deals; the organization merely provides a convenient negotiating venue and a multilateral gloss. Russian and Chinese government representatives, including Putin and Xi, have many other opportunities to meet outside the organization’s purview. In the future, the new BRICS Plus format may provide another multilateral structure for deepening Sino-Russian cooperation and influence in Central Asia. The SCO, lacking substantial organic resources or authority, depends on its members’ sustained contributions. If Moscow and Beijing resume their historical rivalry for Eurasia, the SCO will be doomed to irrelevance.

The PRC’s expanding stakes in Central Asia could lead it to reconsider its policy of regional deference to Moscow. Chinese leaders may, against their will, have to assume a more prominent security role in Central Asia to defend their national interests. They are still developing strategies, tactics, and means to defend their assets. Russian, Central Asian, and Chinese policymakers would prefer that Beijing rely on local elites, supported by Moscow, to protect these assets from terrorist attacks, regime changes, or other threats to its interests in Central Asia.

Nonetheless, the failure of these other actors might compel the PRC and other parties to accept a substantial and enduring PLA presence in Central Asia. Conversely, an end to the Russia-Ukraine War would allow Moscow to redirect resources to bolster its security preeminence in the region. A relaxation of Western sanctions as part of a peace deal would also reduce Central Asia’s importance in helping Russia and China circumvent them.

Implications for US Policy

The US government’s agenda for Central Asia has regularly included multiple goals: fighting terrorism, resolving local conflicts, strengthening border security, supporting democratic and economic reforms, promoting energy production, and enhancing local countries’ autonomy. Whereas in the 1990s US policy focused on state building, economic development, elimination of weapons of mass destruction, and democracy promotion, in the 2000s, counterterrorism rose to the forefront of the US agenda. More recently, the US government has become concerned with countering malign Russian, Chinese, and Iranian influence in Eurasia and securing access to the region’s strategic minerals. Though some issues are manageable in multinational frameworks, it is more effective to address others through bilateral engagement due to each country’s unique characteristics.

Improved economic integration connecting Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and other Central Asian countries would create larger markets, attract more foreign investors, and lower costs through economies of scale. Greater cooperation in the security realm would provide Central Asians with more room to maneuver among the great powers active in the region. It would also reduce the risks of a great-power condominium dominating other Eurasian countries and help these states coordinate responses to economic, political, and security challenges and opportunities. Nonetheless, Kazakhstan’s and Uzbekistan’s ties with Russia, China, and other countries will likely remain close, and perhaps even strengthen, unless extraneous shocks disrupt them.

Several factors have limited Western governments’ influence in Central Asia:

- They have not allocated substantial resources to attain their objectives, choosing to prioritize relations with other regions.

- Western governments and private corporations are more averse than their Russian and especially Chinese counterparts to fund large-scale, high-profile infrastructure projects.

- Due to perennial doubts about US staying power, US officials have found it challenging to assure Central Asians of continued support.

- Geography, history, and economics substantially advantage Russia and China in any contest with the United States for influence in these countries.

- Recent years have made clear the strength of the Sino-Russian alignment, limiting US options for dividing Moscow and Beijing regarding Central Asia or other geographic or functional areas.37

Given these limitations and current US government priorities, the United States may most effectively pursue low-cost but potentially high-impact initiatives, employing a whole-of-society approach that leverages the strengths of its private and nongovernmental sectors. For example, US government experts can collaborate with US commercial entities to make the economies of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan more attractive to American investors through regulatory and rule-of-law reform.38

In particular, corporations can supply unique managerial expertise and other benefits to help bring Kazakhstan’s and Uzbekistan’s strategic minerals to the United States and other global markets. Participating in the extraction process can help ensure US access and supply chain reliability. The US and Uzbekistani governments and private companies have recently launched such an initiative to mine Uzbekistan’s potentially vast deposits of critical minerals.39 Washington should consider repealing Jackson-Vanik legislation for Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan to help solidify economic connections.40 Public-private analytic teams can also help optimize US sanctions to inflict less collateral damage on Kazakhstan and Uzbekistanwhile constraining, rather than incentivizing, sanctions evasion.

In the diplomatic realm, more vigorously highlighting and denouncing sanctions circumvention could disrupt an essential prop of the current Russian war effort and hobble Russia’s postwar military-industrial reconstitution plans. More positively, sustaining the C5+1 (the five Central Asian countries plus the United States) ministerial dialogue and high-level bilateral visits would reaffirm US concern for the region.41 Additionally, encouraging Central Asian states to continue deepening regional integration and cooperation independently of Russia and China would promote geopolitical pluralism in Eurasia.

To assist with security concerns in the region, US agencies can partner with private-sector, open-source intelligence experts to identify and anticipate terrorist and other transnational threats. Continuing US counterterrorism training and related weapons sales would assist Central Asian governments in countering these threats. Finally, the surprising transformation of the Eurasian security environment in recent years, including the US defeat in Afghanistan and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, behooves US defense planners to analyze a wide range of security scenarios regarding Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, including response options to potential unilateral or joint Russian and Chinese military actions affecting either country.