Recently, Japanese Diet (legislature) member Akira Amari spoke at the Hudson Institute in Washington D.C. Mr. Amari is a heavyweight within the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in Japan, having served as Secretary General for the party as well as Economic Revitalization Minister for the late Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. He was so close to Abe, that he was at one point considered likely to deliver Abe’s eulogy before the Japanese Diet. Amari’s words, therefore, should not be taken lightly.

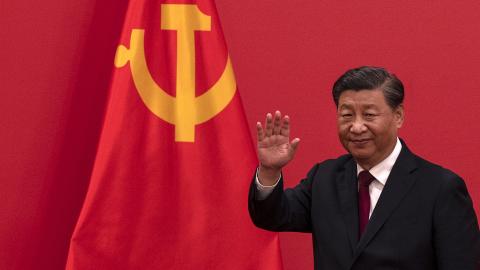

Reflecting concerns that one often hears from Japanese leaders regarding the situation in the Taiwan straits, Amari warned the audience that “today’s Ukraine may be tomorrow’s East Asia.” But the Japanese legislator’s fears clearly went beyond worries about military aggression against Taiwan. He also argued that China’s economic maneuvers — he specifically mentioned Chinese President Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) — should be equally worrisome to the free world. China was attempting to use its economic muscle to create “an international order ruled by itself,” what Amari termed a “Pax Sinica” or “Pax China.” This ought to be countered, he argued, by building up a “Pax Democratica.”

The word “Pax” means “peace” in Latin and is generally used to denote periods of peace and unity that are guaranteed and enforced by a dominant economic and military power. For example, the decades following World War II, when the U.S. was a dominant superpower, at least in the West, is sometimes referred to as a time of “Pax Americana.”

What Amari was implying, however, was that the U.S. did not have to go it alone when competing against China’s attempt at economic hegemony; instead, the U.S. should work with its democratic partners, as it has been doing with Japan, in trying to ensure a free and open Indo-Pacific.

Towards this end, he stated bluntly, “[t]he U.S. should return to the TPP (the Transpacific Partnership).” The TPP, now known as the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), is an 11-nation free trade agreement originally championed by the U.S. and signed by President Obama. President Trump withdrew the U.S. from the agreement shortly after taking office in January of 2017.

Unfortunately, President Biden seems unlikely to heed Amari’s advice regarding the CPTPP. His National Security Adviser, Jake Sullivan, recently argued that the administration wants to “[move] beyond traditional FTA’s (free trade agreements).”

Indeed, the president has not even asked Congress to delegate to him trade promotion authority. Instead, the administration has focused on pseudo trade agreements that do not deal with market access. An example of this would be the Indo-Pacific Economic Partnership (IPEF).

Unfortunately for the U.S., other nations are not ready to abandon negotiating agreements that include, among other provisions, tariff reductions — and they are finding an ally in China.

Although we often focus on China’s increasingly threatening “wolf warrior” military policies, China has been even more aggressive on the economic front. In addition to the BRI, in which China grants development loans to nations that they may have difficulty repaying, China is at the center of a multilateral “mega” trade deal known as the Regional Cooperative Economic Partnership (RCEP), which is even larger than the CPTPP and includes the ten members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) plus important U.S. allies such as Japan, South Korea, and Australia.

At the same time, China has applied to join the CPTPP.

Seeing all of this, it is difficult to not take seriously Mr. Amari’s warnings of an economic Pax China. In fact, China is not hiding its plans. Last month, Wang Shouwen, China’s chief international trade representative, argued that, “[a]dding China [to the CPTPP] would move the region closer to fully realizing the Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific.” Left unspoken but obvious is which nation would be, by far, the center of economic gravity in this trade area.

China’s accension to the CPTPP would have to be agreed to by every current member of the trade pact. While the U.S. can likely depend on Japan and the soon-to-be newest CPTPP member, the UK, to veto China’s acceptance, is the U.S. comfortable outsourcing our economic security to other nations? In refusing to rejoin the CPTPP, that is what we are doing.

Regrettably, the Biden administration’s trade policy does not seem to be guided by economic or geopolitical considerations. Instead, it is domestic politics that those in the White House seem to fear. Like many people inside the beltway, administration officials appear to have convinced themselves that trade is the new “third rail” in American politics. This despite the fact that former President Trump suffered no obvious electoral consequences, at least among voters from supposedly anti-trade states like Ohio or West Virginia, from signing a revised trade deal with Canada and Mexico (the United State-Mexico-Canada Agreement or USMCA) or working out a “stage one” trade deal with Japan.

Interestingly enough, these three countries – Japan, Canada, and Mexico – represent three of the top four economies currently in the CPTPP (the fourth is Australia, with whom we also have an FTA). Academic studies argue that 57% of the text in Trump’s USMCA is from Obama’s TPP.

The agricultural tariff levels achieved through the agreement with Japan are based on the levels Japan agreed to with the other CPTPP countries. In fairness, this means that any economic gains that might accrue to the U.S. by rejoining the CPTPP would be attenuated. By parity of reasoning, economic costs would also be minimal.

It's important to understand, however, that this is not just about economic gains, but also economic security – placing the U.S., rather than China, at the center of Asian trade.

As Mr. Amari noted at the end of his recent talk, “the stability of East Asia, the powder keg of the 21st century,” is contingent upon “the building of U.S. presence and U.S. legitimacy.” Rejoining the TPP, he argued, “can do both of those things.”