There is an emerging international alliance, forged in the face of today’s greatest global threat to freedom and democracy. That threat comes from the China-led, Beijing-Moscow axis of tyranny and aggression. And the new alliance to counter that axis may be called the North-Atlantic-Indo-Pacific Treaty Organization — NAIPTO.

NAIPTO will continue the success of NATO, the world’s most successful multilateral collective defense pact. But it will be augmented by the robust US-led defense alliances in the Indo-Pacific region.

The scale of such an alliance, multilateral, not bilateral, in nature, would be significant, covering Eurasia, as well as the Indian, Atlantic, and Pacific oceans. Such scale is necessary because NATO nations and major countries in the Indo-Pacific region face the same common threat. Common threats are the foundation for common defense.

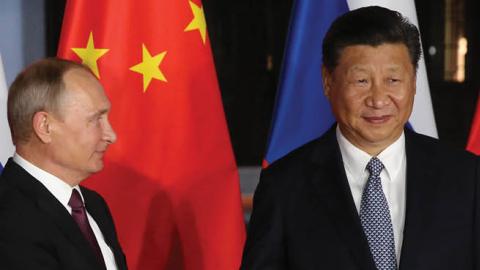

The urgency of this alliance has become more acute in recent months. Russia’s war on Ukraine crystalizes the common sources of aggression by the world’s two remaining civilization states: China and Russia.

Neither country bases its claims to other nations’ territory on nation-state sovereignty or international law. The justifications are civilizational, stressing ethno-linguistic heritage and historical nihilism. China and Russia form a revisionist coalition across the Eurasian continent. The Beijing-Moscow axis must be countered with a Eurasian, trans-oceanic alliance.

China and Russia have much in common. They are geopolitical revisionists, bent on destroying the US-led international legal and political system that promotes and protects peace, democracy, and the free-market system. They have committed to an “uncapped fraternity,” and support each other rhetorically and practically in places such as Ukraine and Taiwan. They view democratic alliance systems in Europe and Asia with hostility. Making their common hostility abundantly clear, in the last day of US President Joe Biden’s recent visit to Tokyo for the Quad meeting, a joint Russian-Chinese bomber patrol gave him a sendoff above the Sea of Japan.

This show of force was deliberate. Hu Xijin (胡錫進), China’s prominent propagandist, an expert in human duplicity, described it this way: “This joint strategic patrol of China and Russia is aiming at the Quad summit in Tokyo. Don’t mess with China and Russia, especially don’t mess with these two great powers at the same time.”

Democratic nations should take the China-Russia bloc at its word. Russia threatens freedom and democracy in Europe. China threatens freedom and democracy in the Indo-Pacific, and around the world. Together, they form a global axis. NAIPTO would be a powerful, global, democratic response that would renew confidence in freedom’s strength and durability.

NAIPTO would eliminate the most significant limitation to the US-led alliance in the Indo-Pacific: the inadequacy of America’s bilateral alliances in the region. NATO is a multilateral alliance, but America’s alliance system in the Indo-Pacific is bilateral. The US has strong defense agreements with key allies in Asia, including Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and Thailand. But those nations do not have mutual defense arrangements for multilateral defense.

This deficiency creates challenges. For example, if and when China attacks Japan, Washington would be obliged to fight alongside Tokyo. But US allies, including South Korea and the Philippines, would not be. The same applies to analogous scenarios, creating windows for Chinese manipulation, and allowing Beijing to play one US ally against the other. To take one case, Beijing has a history of exploiting longstanding grievances between Seoul and Tokyo, working to split potential Washington-Tokyo-Seoul tripartite cooperation.

As the United States shifts its strategic priorities away from Europe to the Indo-Pacific, momentum for NAIPTO will grow. The US is currently responsible for approximately 75 percent of NATO’s military spending. This has created a NATO overdependency on the US for European security while Washington has placed China and the Indo-Pacific at the top of its national security priority agenda. Russia’s brutal war in Ukraine has, of course, put the spotlight back on Europe, but the Allies can no longer afford to treat Russia, and not China, as their preponderant rival.

Allowing Russia’s regional gambits in Europe to distract from the much more formidable global challenge posed by China would be an unthinkable blunder. China’s economy is more than ten times larger than Russia’s. Its military capabilities, including both conventional and high-tech arenas such as cyber, space, and artificial intelligence are far more advanced. And its ambition is not only to relive its imperial past by threatening its neighbors, as is the case with Russia, but also to remold the US-led international order into a Beijing-centric communist system. Russia is seeking global relevance. China is seeking global dominance.

NAIPTO’s critics will say that similar ideas have failed in the past. There was an attempt in the 1950s to form an Asian NATO, which became the Southeast Asian Treaty Organization, or SEATO. That attempt was unsuccessful.

But the reasons for SEATO’s failure are long gone, paving the way for a new multilateral common defense alliance in the region. In the 1950s, most countries in Southeast Asia had only just emerged from European colonialism. There were significant threats from communists in China, North Korea, and North Vietnam, but their animosity toward European powers was just as strong as their dislike of communism. As a result, when SEATO was created, only two nations in Southeast Asia, the Philippines and Thailand, became members. Other SEATO founding member states were the US, France, Great Britain, New Zealand, Australia, and Pakistan.

Today, the threat from China has gone from remote to acute, from regional to a much wider swath of the globe, and it is shared by nearly every major country in the Indo-Pacific region, including Japan, India, South Korea, Taiwan, Australia, New Zealand, and the ten ASEAN nations. More than half of these countries have maritime and territorial disputes with the Chinese Communist Party. Never in history has there been a clearer, more common threat to free and sovereign nations in the Indo-Pacific region as the one posed today by China.

SEATO also failed because, unlike NATO countries, Asian nations at the time did not have strong and shared values and democratic institutions. Many nations — even US allies and partners like Taiwan, South Korea, and the Philippines — were ruled by dictators at the time. The US-led alliance system’s primary objective is America’s security and the defense of values like democracy, human rights, and the rule of law. Given the poverty of such values in Asian nations in the 1950s, which forced the US to go bilateral instead of multilateral, SEATO as an Asian NATO with a multilateral framework was doomed from the start.

But the world has changed since the twilight years of the last Cold War. Beginning with the 1986 People’s Power movement in the Philippines, a wave of democratization swept the Indo-Pacific. Democracies have long become a norm rather than an aberration. Peoples in Taiwan, South Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia, and many other countries have joined democracies like Japan, India, Australia, and New Zealand. While differences remain, these countries’ current like-mindedness gives an emerging NAIPTO a strong foundation for the common defense of sovereignty and fundamental freedoms.

A coalition of the willing, NAIPTO’s multilateral structure will further deepen ties, moving members beyond parochial, historical squabbles, and placing the common defense over narrow self-interest. NATO has, for decades, pacified Europeans’ longstanding internecine battles and internal strife. NAIPTO has the potential to do the same in the Indo-Pacific for countries like South Korea and Japan, as well as others.

While the ambition of the NAIPTO alliance might make some hesitant, a Eurasian democratic alliance is not only necessary, but also within reach. The United States was one of the first countries to wake up to the China challenge, and many Europeans now agree with America’s strategic shift. The European Union has labeled China a “systemic rival.”

Likewise, NATO’s leadership continues to make landmark statements on the need for the widening Alliance to take on a new mission to promote peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific. For the first time in the Alliance’s history, the recent NATO Summit in Madrid included the president of South Korea, as well as prime ministers of Australia, Japan, and New Zealand. The NATO 2022 Strategic Concept produced at that meeting was not only revolutionary, but also substantive, declaring that NATO countries must “work together responsibly, as Allies, to address the systemic challenges posed by the [People’s Republic of China] to Euro-Atlantic security.”

The time has come to give new strength and purpose to old alliances, and to build new ones to meet today’s challenges. If we treasure the success of NATO in the 20th century, the best way to ensure that the gains it made possible is to endure and expand its promise to NAIPTO in the 21st, for an attack on one democracy is an attack on all democracies regardless of geographic boundaries.