History was made at the White House on August 8, 2025, when President Donald Trump hosted Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev for a landmark meeting. Against all odds, and after more than three decades of failed diplomacy by the international community, the two leaders from the Caucasus signed a joint declaration committing to a final peace treaty that will normalize relations between their countries. Their foreign ministers also initialed a draft version of that treaty, which the countries plan on fully ratifying within the next 12 months.

Diplomats brokered this breakthrough not in Moscow, Paris, or Brussels—but in Washington. For decades, the South Caucasus has been a flashpoint for regional competition, unresolved wars, and missed diplomatic opportunities. Now, with US reengagement, real peace between Armenia and Azerbaijan may finally be within reach.

It is reasonable to assume that President Trump’s instinctive urge to cut deals—along with his desire to go down in history as an international peacemaker and statesman—drove his determination to lead efforts to end the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict. The deal also gave him the chance to tie up a loose end from his first administration. Despite Trump’s frequent claims that no new wars started under his watch, the 2020 Second Karabakh War erupted in the final year of his presidency. His administration made no meaningful effort to bring it to a close, creating a vacuum that Moscow filled by brokering a ceasefire agreement—one it ultimately proved unable to enforce.

But President Trump could also recognize an opportunity when presented with one. In many ways, he was pushing at an open door. Both Armenia and Azerbaijan understand the importance of normalization and peace. Both are also exhausted by Moscow’s failed mediation efforts and its waning regional clout.

The White House would be mistaken in assuming that since the headlines have passed, the cameras have stopped recording, and the signing ceremony is complete, the job is finished. Three big challenges are still on the horizon:

- Questions remain about Prime Minister Pashinyan’s political stability, which could be undermined, especially in the lead-up to Armenia’s parliamentary elections next June, as hardline nationalists and Moscow-backed groups inside Armenia challenge his authority and the legitimacy of the peace process.

- Both Armenia and Azerbaijan should expect Russia and Iran to try to discredit the peace process by launching disinformation campaigns.

- Many questions remain unanswered about how the regional transport links envisioned in the peace agreement—including the Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP)—will be funded and financed.

Without a resolution of these challenges, President Trump might lose interest in the peace initiative. Only his direct oversight can ensure its success.

Armenia-Azerbaijan: An Overview

Before analyzing the geopolitical significance of the agreement, a review of this conflict’s recent history can offer a better understanding of how the future could unfold.

The roots of the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict go back to the final years of the Soviet Union. In 1988, the local assembly of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO), an administrative division of the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR) with a majority ethnic Armenian population, voted to join the Armenian SSR. In December 1991, the NKAO’s ethnic Armenian authorities held a referendum on independence, which the Azerbaijani minority boycotted. The Soviet and Azerbaijani governments considered both the local assembly vote in 1988 and the referendum in 1991 illegitimate, and this eventually led to a bloody war as Armenia and Armenian-backed separatists fought Azerbaijan, leaving 30,000 people dead and many hundreds of thousands internally displaced.

Upon the Soviet Union’s dissolution in late 1991, the newly independent countries of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan signed the Alma-Ata Protocols, which stated that the signatories are committed to “recognizing and respecting each other’s territorial integrity and the inviolability of the existing borders.” This included having Azerbaijan SSR’s Karabakh region remain part of the new Republic of Azerbaijan. But by the time the protocols came into effect, Armenia had effectively disregarded the border principle regarding Nagorno-Karabakh, and the Armenians and Azerbaijanis were already at war.

In 1992, Armenian forces and Armenian-backed militias occupied the Karabakh region and all or parts of Azerbaijan’s Aghdham, Fuzuli, Jabrayil, Kalbajar, Lachin, Qubadli, and Zangilan Districts. On this occupied territory, Armenian separatists declared the so-called Republic of Artsakh, which no country ever recognized—not even Armenia.

During 1992 and 1993, the United Nations Security Council adopted four binding resolutions addressing the conflict:

- Resolution 822 (April 30, 1993) called for the cessation of hostilities and withdrawal of Armenian forces from the Kalbajar District.

- Resolution 853 (July 29, 1993) demanded the withdrawal of occupying forces from the Agdam District and other recently occupied territories of Azerbaijan.

- Resolution 874 (October 14, 1993) called for implementation of the previous resolutions and endorsed the peace plan known as the “Adjusted Timetable of Urgent Steps,” proposed by the Minsk Group, which was established by the Organisation of Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) in 1992 to help resolve the conflict.

- Resolution 884 (November 12, 1993) condemned the occupation of Zangilan and the city of Goradiz (today known as Horadiz), reaffirmed earlier resolutions, and again called for the occupying forces to withdraw from Azerbaijan.

Each resolution also reaffirmed the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan and called for the return of displaced persons.

After years of only minor skirmishes, intense fighting flared up in April 2016, leaving around 200 dead on each side. During this short conflict, Azerbaijani forces regained more than eight square miles of territory, including the strategic hilltop of Leletepe near the Iranian border. In 2018, Azerbaijani troops made additional gains around the strategically located village of Günnüt in Nakhchivan.

Then, in 2020, Azerbaijan launched a military operation known as the Second Karabakh War and regained much of the land it lost in the 1990s. Russia stepped in to mediate a ceasefire, inserting peacekeepers into the region and allowing Armenia to retain a portion of Karabakh, but this arrangement was always fragile. In September 2023, after a 24-hour military operation, Azerbaijan reasserted full control of the territory, and Russian troops quietly withdrew.

Since then, both countries have expressed a desire for a comprehensive peace, but the process has stalled, largely due to mistrust and Moscow’s waning credibility. Historically, Russia has used the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict as leverage to maintain influence in the South Caucasus. Neither Baku nor Yerevan trusts Moscow to be a neutral broker anymore.

Despite years of diplomatic effort, the Minsk Group—which was co-chaired by France, Russia, and the United States—failed to produce a framework acceptable to all sides and eventually lost relevance. On September 1, 2025, the OSCE Ministerial Council adopted a decision to disband the group, with the process to be completed by December 1.

Enter the United States. By hosting the leaders at the White House, President Trump filled the diplomatic vacuum left by Russia’s decline and Europe’s inertia. The signed declaration and initialed treaty draft are remarkable accomplishments.

The Hard Work Begins

In many ways, the hard work begins now. Both sides have committed to ratifying the peace treaty over the course of the next year. Two major issues will need to be addressed before ratification is possible: (1) crucial changes to Armenia’s constitution and (2) visible and real progress on creating and implementing TRIPP.

Amending Armenia’s Constitution to Remove Territorial Claims to Azerbaijan

An essential step for advancing peace is reforming the Armenian constitution, which contains an implied territorial claim against Azerbaijan through its reference to the 1990 Declaration of Independence. That declaration rests on the joint decision of the Armenian SSR Supreme Council and the so-called Artsakh National Council of December 1, 1989, which explicitly stated:

The Armenian Supreme Soviet and NKAO National Council declare the reunification of the Armenian Republic and the NKAO. The Armenian Republic citizenship rights extend over the population of the NKAO.

The Declaration of Independence, adopted on August 23, 1990, opened with the following language:

Based on the December 1, 1989, joint decision of the Armenian SSR Supreme Council and the Artsakh National Council on the reunification of the Armenian SSR and the Mountainous Region of Karabakh . . .

When Armenia adopted its constitution in 1995, the preamble carried this forward, declaring:

The Armenian People, accepting as a basis the fundamental principles of Armenian statehood and pan-national aspirations enshrined in the Declaration on the Independence of Armenia, adopt the Constitution of the Republic of Armenia.

Taken together, these texts mean that Armenia’s constitutional order is formally grounded in a founding act that asserts a claim to Azerbaijan’s Karabakh region.

For Baku, this is not a semantic matter but a structural obstacle to peace. As President Aliyev recently stated, “As soon as this amendment to the constitution is made and territorial claims to Azerbaijan are deducted from the constitution, the formal peace agreement will be signed.” As long as Armenia’s constitution embeds language derived from a document that references unification with Azerbaijani land, Azerbaijan will question Armenia’s sincerity about recognizing its territorial integrity. Amending the constitution to remove these references would not only address Azerbaijan’s concerns but also demonstrate Armenia’s seriousness about normalization and closure of the territorial dispute.

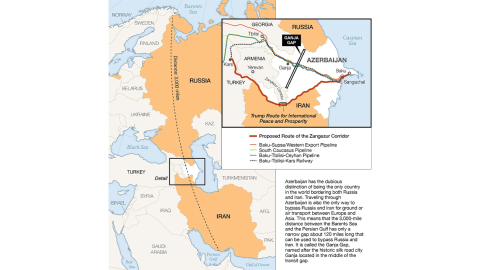

Map 1: Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity

Source: Hudson Institute research.

Opening Transit Routes: Creating and Implementing TRIPP

Another significant matter that will have to be addressed is whether progress is being made on opening regional transport links, specifically the so-called Zangezur Corridor. Under the 2020 ceasefire agreement brokered by Russia, which ended the 44-day Second Karabakh War, Armenia agreed in principle to allow such connections.

Article 9: All economic and transport connections in the region shall be unblocked. The Republic of Armenia shall guarantee the security of transport connections between the western regions of the Republic of Azerbaijan and the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic in order to organize the unimpeded movement of citizens, vehicles, and cargo in both directions.

Almost five years later, however, this has not been implemented, which is understandably frustrating for Azerbaijan because another article in the same agreement imposed obligations on Baku.

Article 6: “The Lachin corridor (5 km wide), which will ensure the connection of Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia and at the same time will not affect the city of Shusha, remains under the control of the peacekeeping contingent of the Russian Federation. . . . The Republic of Azerbaijan guarantees the safety of traffic along the Lachin corridor of citizens, vehicles and goods in both directions.”

Azerbaijan, unlike Armenia, fulfilled its obligation—and did so ahead of schedule. Article 6 gave Baku three years to build a new road connecting Armenia proper with the ethnic Armenian region of Karabakh, but the project was completed in July 2022, well before the deadline. The contrast is stark: While Azerbaijan met its commitments under Article 6, Armenia has failed to deliver on its responsibilities under Article 9. For Baku, the lack of reciprocity from Yerevan has been a source of mounting frustration.

To address this impasse, the White House proposed a novel idea: the Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity, or TRIPP, a US-led initiative to facilitate the opening of a secure transit corridor through Armenia, linking Azerbaijan proper with its exclave of Nakhchivan while preserving Armenia’s sovereignty over its territory. A private US-backed firm is slated to manage the corridor’s logistics and security in coordination with Armenian authorities. Construction is expected to begin before the end of the year, with the route envisioned to be fully operational before President Trump leaves office.

The logistical challenges are formidable. The portion of Armenia’s Syunik Province that separates Azerbaijan from Nakhchivan is only about 26 miles wide, but the road and rail infrastructure that once connected the two has been derelict for decades due to the conflict. During the Soviet period, both a highway and a railway linked Azerbaijan proper with Nakhchivan. The Nakhchivan–Meghri–Baku segment of the old Kars–Gyumri–Nakhchivan–Meghri–Baku (KGNMB) rail line served both freight and passenger trains. Interestingly, although the line passed through what today is Syunik Province in Armenia (during Soviet times, the Meghri raion), it was administered by the Azerbaijan SSR’s railway administration rather than the Armenian SSR.

With the outbreak of the First Karabakh War in 1991, all direct transport links were severed, and the railway south of Horadiz in Azerbaijan was abandoned after falling under Armenian control. Much of the track and related infrastructure along this route has since fallen into disrepair. According to a 2014 report by the nongovernmental organization International Alert, the section of rail running from Horadiz through Armenia’s Syunik Province and into Nakhchivan is classified as “category 4”—meaning the line is completely wrecked and requires total restoration.

Since regaining control over its territory, Azerbaijan has been refurbishing the Horadiz–Agband railway line, which will ensure that TRIPP is connected to the rest of Azerbaijan proper. Construction began in 2021 and is expected to be completed by the end of this year. The main axis runs about 69 miles and has three tunnels, 41 bridges, and seven overpasses. Ultimately, it will connect Horadiz with Agband, on Azerbaijan’s border with Armenia. From this point, TRIPP would be constructed to connect with Nakhchivan.

The road network is little better. The main route is designated E-002, a European B-class road. In much of the South Caucasus, B-class roads are underdeveloped, and this section is no exception. Given that the E-002 has not been used for decades for its original purpose of linking Azerbaijan with Nakhchivan, deterioration is significant. Some sections remain unpaved gravel, and many bridges will likely require major repairs or full replacement.

The TRIPP initiative seeks to overcome these obstacles by mobilizing US political will, international investment, and local cooperation. Yet the task of transforming a neglected transport corridor in one of the most geopolitically sensitive areas of the South Caucasus into a functioning international route will be neither easy nor straightforward.

The Peace Agreement: Regional Implications

There is no doubt that Armenia-Azerbaijan normalization would bring great benefits to both countries. For Azerbaijan, it resolves a decades-long geopolitical challenge: securing its territorial integrity against outside aggression while also achieving the long-sought transport and communication links to its Nakhchivan enclave. For Armenia, peace with Azerbaijan promises political stability at home and the prospect of economic growth, building on a centuries-old tradition of local and regional trade between the two peoples. With peace, new investment opportunities will likely emerge that were impossible during decades of conflict. Considering Armenia’s fragile economy, normalization with both Azerbaijan and Türkiye could bring untold economic benefits in the long term. Moreover, it could give Armenian leaders the political space needed to pursue closer relations with the Euro-Atlantic community.

Different countries in the region and beyond will view the Armenia-Azerbaijan peace agreement in different ways. But once it is ratified—and once provisions such as the TRIPP are realized—there is little doubt that the geopolitical landscape in the South Caucasus will change. Such changes will not occur in a vacuum; they will have second- and third-order effects across the region and beyond.

Russia: Moscow faces waning influence and growing insecurity. Russia views the peace agreement with nervousness. Its influence in the South Caucasus has been steadily declining since 2022, largely due to the war in Ukraine. Relations with both Armenia and Azerbaijan are strained. Many Armenians believe that during the 2020 Karabakh war, Moscow failed to uphold its commitments under the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), making them view Russia as an unreliable partner. Meanwhile, Russia’s relations with Azerbaijan worsened after the downing of an Azerbaijani Airlines passenger plane in December 2024 killed dozens of civilians, an act Moscow never formally acknowledged. With the United States now leading the peace process in a region where Russia once dominated, Moscow will likely shift its focus more intently toward Georgia. A wildcard scenario could even see Russian interference in Armenian politics to install a leader more aligned with Moscow’s interests.

Iran: Tehran emerges as the biggest geopolitical loser. Although Iran and Azerbaijan maintain cordial relations publicly, beneath the surface ties are tense and at times confrontational. Azerbaijan is uneasy about Tehran’s treatment of ethnic Azerbaijanis in northern Iran as well as Iran’s decades of support for Armenia during the Karabakh conflict. The two also continue to dispute maritime boundaries in the Caspian Sea. In recent years, however, Baku has relied on Tehran to resupply its Nakhchivan exclave—through road and air access as well as a gas-swap arrangement with Turkmenistan. With the creation of TRIPP and the recent completion of the natural gas pipeline linking Türkiye to Nakhchivan, Iran’s leverage over Baku is sharply diminished. Even more concerning for Tehran, the United States will now have an indirect role in operating a 26-mile stretch of its northern border with Armenia.

Türkiye: Ankara is the region’s biggest winner. The peace agreement and the creation of TRIPP enhance the resilience of east–west transport routes linking Türkiye to the heart of Eurasia. Currently, Türkiye’s primary eastward route passes through Georgia into Azerbaijan and then across the Caspian Sea. TRIPP is not intended to replace this corridor but to complement it, providing an alternative route that ensures continuity of trade even if the Georgian corridor is disrupted. Currently, the Turks are constructing a new rail line linking Kars with Dilucu, located on Türkiye’s border with Nakhchivan. This will eventually connect to the TRIPP and on to Central Asia. Another implication for Ankara is the new political space created for normalization with Armenia. Although Türkiye was one of the first countries to recognize Armenia’s independence in 1991, relations quickly deteriorated after Armenia’s invasion of Azerbaijani territories in the early 1990s. With peace between Yerevan and Baku on track, new opportunities for Ankara-Yerevan reconciliation are beginning to emerge.

The Organization of Turkic States: An emerging bloc is reshaping Eurasia. The peace agreement strengthens the Organization of Turkic States (OTS) and accelerates Turkic cohesion across Eurasia. Collectively, the OTS represents an emerging geopolitical pole in Eurasia, increasingly capable of challenging Russian influence. Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan publicly supported fellow OTS member Azerbaijan against Armenia during the recent conflict, demonstrating allegiance to the OTS over the Moscow-backed CSTO, of which Armenia was then a member. Since regaining independence in the early 1990s, the Central Asian republics, along with Azerbaijan, have sought to shed their Russian-imposed cultural links in favor of reviving their Turkic roots, culture, and shared history. This trend is reinforced by Turkish soft power, with millions of Turkic-speaking people—from southeastern Europe to eastern China and up into the Arctic—consuming Turkish cinema, music, and television. TRIPP’s creation will only encourage OTS members to expand cooperation, particularly in trade, energy, and economic integration.

Map 2: Proposed Rail Line from Kars to Baku

Source: Hudson Institute research. Note: Routes are approximate.

The United States: While not a Eurasian country, it is an emerging Eurasian power. Peace between Armenia and Azerbaijan creates a long-overdue opening for greater US engagement in the South Caucasus and beyond. The last US Central Asia strategy, released in February 2020, is already outdated given the scale of regional changes since then—from the US withdrawal from Afghanistan to the Second Karabakh War to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The South Caucasus, and Azerbaijan in particular, is a key geographic and transit gateway for the United States and Europe into Central Asia. Normalization of relations between Armenia and Azerbaijan, coupled with the creation of TRIPP, represents a rare diplomatic success for Washington in Eurasia. The United States should seize this momentum to project influence in the region as a resident power, shaping outcomes in ways not seen for decades.

While plenty of fanfare and optimism has surrounded the progress made by Armenia and Azerbaijan in ending their three-decade conflict, there remains unfinished business in the South Caucasus. Since 2008, Russia has occupied roughly 20 percent of neighboring Georgia—specifically the Abkhazia region and the Tskhinvali region, commonly known as South Ossetia. Moscow uses this military presence not only to project power across the region but also to influence Georgia’s domestic politics. As Russia’s sway diminishes in Armenia and Azerbaijan, it will continue to rely on its foothold in Georgia as its primary lever of influence in the South Caucasus. US policymakers cannot overlook this reality and need to craft policies that strengthen Georgia’s resilience and advance both regional stability and US interests.

Recommendations

President Trump’s South Caucasus diplomatic initiative opens up a new opportunity for Washington to become more engaged in the region. Given the multitude of geopolitical challenges the US faces—including a belligerent Russia, the proliferation of transnational terrorist groups, an emboldened China, and an increasingly aggressive Iran—it makes sense for Washington to be active in Eurasia. The US should seek to weaken Russian and Iranian influence in the region while promoting political stability, economic prosperity, national sovereignty, and security. To do so, it should take the following steps:

- Build on the momentum from the strategic agreements the United States, Azerbaijan, and Armenia signed at the White House.

- For Azerbaijan: Focus on maritime security and counterterrorism cooperation. The United States and Azerbaijan have had a good security, intelligence, and counterterrorism relationship since 9/11, although at times certain lobby and pressure groups in Washington have made cooperation and practice difficult. Section 907 of the Freedom Support Act, which uniquely singles out Azerbaijan as the only former Soviet states that cannot receive any US assistance, is an unfair impediment to action in the interest of US security. One of the biggest maritime capability gaps in the Caspian is maritime domain awareness, so the US should focus on providing coastal radar stations, radar for ships, and communication equipment to help improve command and control. Washington should provide the Azerbaijani Navy with training opportunities, officer exchanges, and equipment modernization wherever possible.

- For Armenia: Pursue policies that bring Armenia closer to the Euro-Atlantic community, while remaining realistic about Russia’s influence. Armenia should deepen ties with the United States and the European Union, but Moscow still wields significant leverage. Russia maintains the 102nd Military Base in Gyumri, an airbase near Yerevan, and border guards along Armenia’s frontiers with Türkiye and Iran. Even as relations with Moscow have soured since the 2020 war, these deployments ensure Russia retains influence over Armenia’s security and foreign policy. Policymakers should not expect any sudden shifts in Armenia’s orientation but should instead take a long-term and strategic approach.

- Make quick progress on TRIPP. Since this transit route is branded with the Trump name, the president needs to take a direct role in ensuring the project’s completion and success. Many questions remain about which international businesses will form the consortium that runs and manages the route and how the financing and funding will take place. If resolving these questions becomes difficult, US policymakers could lose interest in the project, leading to significant delays. Since Azerbaijan agreed to peace with Armenia on the premise that such a transit route would be established, not completing the project could prevent ratification of the peace agreement.

- Push for construction of the trans-Caspian natural gas pipeline. Just as the Clinton administration provided diplomatic and political support for the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan oil pipeline in the 1990s, the Trump administration should use its newfound diplomatic momentum to work with Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan for construction of a trans-Caspian gas pipeline that could connect Turkmenistan’s vast natural gas resources to European markets. In the short term, this could be quickly accomplished by an interconnector linking up Turkmen and Azerbaijani gas fields in the Caspian that are only 60 miles apart. An interconnector would serve as a confidence-building measure between the two sides and a proof of concept that could eventually lead to a fully developed gas pipeline under the Caspian.

- Build closer relations with the OTS. Turkic influence is on the rise across much of Eurasia, and the OTS is only going to grow in geopolitical significance and importance in the coming years, especially as Russian influence wanes and China focuses more on the Indo-Pacific. The United States should start building an institutional relationship with the OTS as it does with other regional and political organizations and blocs around the world. For starters, Secretary of State Marco Rubio should meet the OTS secretary-general in order to start an official dialogue.

- Develop a Central Asia strategy that links the region more effectively to new South Caucasus transit routes. It has been more than half a decade since the US last launched a Central Asia strategy. A new approach to the region is long overdue—one that takes account of the new geopolitical realities in Central Asia. The focus of the next Central Asia strategy should be on connectivity, and it should capitalize on the recent transport and energy initiatives in the South Caucasus (such as the Southern Gas Corridor and possibly TRIPP) and how they can best be linked to Central Asia to increase regional connectivity.

- Offer political and commercial support for new transit links. The United States should support the creation of new transit links that connect Armenia to the rest of the region and promote joint Armenia-Azerbaijan infrastructure projects, particularly those that can build confidence. Armenia has missed out on many important regional energy and transport infrastructure projects due to more than three decades of conflict in the South Caucasus. Washington should support new projects that connect Armenia to its neighbors and help integrate it into the region. If there is genuine peace and a trans-Caspian pipeline is built, regional governments could work to create a Turkmenistan–Azerbaijan–Armenia–Nakhchivan–Türkiye gas pipeline. The idea would not be to compete with the Southern Gas Corridor, which currently serves as the region’s main pipeline network delivering gas to Europe while bypassing Armenia. Instead, such an ambitious project could help integrate the region, build trust among old adversaries, and aid Armenia with its energy issues. While the region is probably years away from the diplomatic conditions required for such a project, the US should start a discussion now on what is possible.

- Expand the US diplomatic presence in the region. In addition to committing to more senior-level visits, the United States should consider establishing a presence—a consulate general, consular agency, or other permanent outpost—in several strategic locations in the region:

- Ganja, Azerbaijan, the country’s second-largest city, which is strategically located on one of the most important trade choke points on the Eurasian landmass, the Ganja Gap.

- Kapan, Armenia, located in Armenia’s Syunik Province and also located near TRIPP. Tehran recently opened a consulate there, knowing that southern Armenia will become a focal point for regional transport links.

- Increase the US political presence in the region. President Trump should visit Armenia and Azerbaijan, and thus become the first sitting US president to do so. In the past two decades, there has been a lack of high-level US engagement across Eurasia. No sitting American president has visited Armenia, Azerbaijan, or any of the five Central Asian republics. Visits to the region by cabinet-level officials have also been infrequent. Secretaries of State John Kerry, Mike Pompeo, and Antony Blinken each made only one visit to Central Asia. The last secretary of state to visit Armenia or Azerbaijan was Hillary Clinton in 2012, and Donald Rumsfeld was the last secretary of defense to visit Central Asia, in 2006. The last secretary of defense to visit Azerbaijan was Bob Gates in 2010, and no secretary of defense has visited Armenia since Donald Rumsfeld in 2001. The region is long overdue for a high-level US visit, which would help ensure that President Trump’s peace plan comes to fruition.

- Push for normalization between Türkiye and Armenia. Once Armenia and Azerbaijan formally ratify the peace agreement and relations between the two are normalized, Türkiye should be strongly encouraged to pursue normalization with Armenia. The reopening of borders and the re-establishment of diplomatic relations between the two could enhance the transit and economic viability of the South Caucasus and help set the conditions for a lasting regional peace. President Trump could be well placed to work now with both sides behind the scenes to ensure that someday normalization.