11

November 2025

Past Event

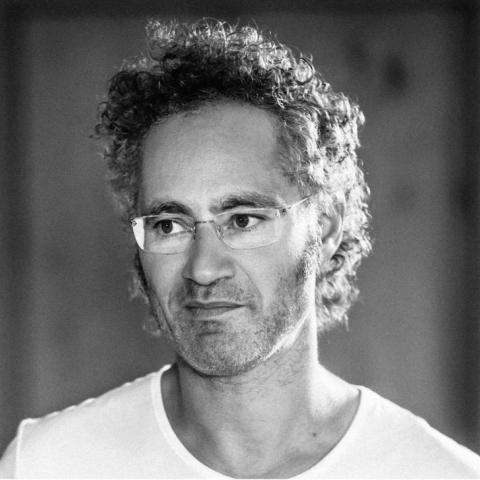

Palantir CEO Alex Karp Receives Hudson Institute’s 2025 Herman Kahn Award

Palantir CEO Alex Karp Receives Hudson Institute’s 2025 Herman Kahn Award

Past Event

New York

November 11, 2025

Share:

Caption

Dr. Alex Karp at Hudson Institute’s annual gala in New York on November 11, 2025.

Related Events

12

February 2026

In-Person Event | Invite Only

Opportunity and Uncertainty in the Middle East: Next Steps for the Kurdistan Region of Iraq

Featured Speakers:

Rebar Ahmed

Joel Rayburn

12

February 2026

In-Person Event | Invite Only

Opportunity and Uncertainty in the Middle East: Next Steps for the Kurdistan Region of Iraq

Join Hudson for a deep dive into these topics with Interior Minister of the Kurdistan Regional Government Rebar Ahmed, one of the region’s most experienced and respected statesmen.

Featured Speakers:

Rebar Ahmed

Joel Rayburn

13

February 2026

In-Person Event | Hudson Institute

A Strategic Response to Sino-Russian Cooperation: Perspectives from Europe and the Indo-Pacific

Featured Speakers:

Nishank Motwani

Patrick M. Cronin

Justyna Szczudlik

Moderator:

Masashi Murano

10

February 2026

Past Event

Gen. Pierre Schill on France’s Strategic Vision and Adapting Land Forces for High-Intensity Conflict

Featured Speakers:

General Pierre Schill

Rebeccah L. Heinrichs

10

February 2026

Past Event

Gen. Pierre Schill on France’s Strategic Vision and Adapting Land Forces for High-Intensity Conflict

Hudson welcomes French Army Chief of Staff General Pierre Schill, one of Europe’s most senior military leaders, for a discussion on the evolving strategic environment and the French Army’s transformation in a rapidly changing world.

Featured Speakers:

General Pierre Schill

Rebeccah L. Heinrichs

10

February 2026

Past Event

Year One of Trump’s Foreign Policy: A Discussion with Congressman Pat Fallon

Featured Speakers:

Rebeccah L. Heinrichs

Congressman Pat Fallon

10

February 2026

Past Event

Year One of Trump’s Foreign Policy: A Discussion with Congressman Pat Fallon

Join Senior Fellow Rebeccah Heinrichs and Congressman Pat Fallon (R-TX) for a discussion on the Trump administration’s first year of foreign policy and the risks and opportunities ahead.

Featured Speakers:

Rebeccah L. Heinrichs

Congressman Pat Fallon